Between 1930 and 1931, near the town of Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, 3,000 men worked in ten-hour shifts drilling a three-mile tunnel through the side of a mountain. Within five years, more than 750 of those men would die of a deadly and preventable disease. Keep reading as we use HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and U.S. Congressional Documents collection to learn more about the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster, the single deadliest industrial incident in American history, and its influence on the struggles for worker’s rights and safety regulations in the United States.

Incident at Hawk’s Nest

In 1927, the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, a large firm that specialized in the sourcing of carbon for industrial purposes, created the New Kanawha Power Company, for the purpose of developing a hydroelectric project to provide power for another one of its subsidiaries, the Electro Metallurgical Company. After securing a permit from the state of West Virginia, New Kanawha Power awarded a contract to Rinehart and Dennis to begin work on a tunnel to divert water for the project.

The project was an ambitious one, with the design calling for a three-mile long tunnel to be drilled straight through the heart of Gauley Mountain, underneath the dramatic cliff face of Hawk’s Nest, after which the tunnel was named. The contractors were awarded the project with an aggressive two-year timeline,[1]Jessica L. Toler, Dead Canaries: The Struggle of Appalachian Coal Miners to Get Black Lung Benefits, 6 J. GENDER RACE & JUST. 163 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. with cash incentives for completing the project ahead of schedule. Fortunately for Rinehart and Dennis, the drilling of Hawk’s Nest Tunnel was defined as a construction project, and not a mining project, allowing them to circumvent even the minimal safety regulations that protected miners at the time.

Drilling commenced in May 1930, only 18 days after the project received final approval from the state of West Virginia. Gauley Mountain was made up primarily of sandstone, 90-97% of which was composed of silica, the common term for silicon dioxide, which is a primary component for manufacturing glass and a valuable material for industrial smelting. The Hawk’s Nest tunnel was technically a drilling operation, not a mining operation, but the company was permitted to extract and use any silica produced as a byproduct of their tunneling. When Union Carbide learned of the existence of silica of such purity in Gauley Mountain, they expanded the size of the tunnel, from its planned 36 feet to 42 feet in diameter, to expedite the extraction of the valuable material.

To save time and meet their deadline, and extract as much silica as possible, Rinehart and Dennis employed primarily dry drilling in the tunnel. Typically, safety protocols would call for wet drilling in such an environment, in which water is applied to the drilling surface to suppress clouds of particulate matter. However, wet drilling is slower and more expensive than dry drilling.[2]Vito Marcantonio. I Vote My Conscience (1956). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. Facing a tight deadline and substantial cash incentives, management opted for the quicker and more efficient method.

The dry drills kicked up dust, and a lot of it. Workers inside the tunnel reported being unable to see more than ten feet in front of themselves while the drills operated. Men exited the tunnels caked head to toe in dust. Within weeks of work starting, men began to fall ill with a condition that was referred to, euphemistically, as “tunnelitis.”

“Men died like flies.”

“Tunnelitis” referred to what we know to be silicosis, a disease that afflicts people exposed to airborne particles of silica. Silica dust is, essentially, a cloud of small fragments of glass. When someone inhales silica, it cuts into the lungs, creating scar tissue. With sufficient exposure, over a sufficient period of time, this scar tissue begins to impede breathing, to the point of death if it continues.

The pathology of silicosis was widely known in 1930, as the disease had been extensively documented since at least the early 18th century (perhaps earlier), under a variety of names, such as potter’s rot and quarryman’s disease.[3]A. Meiklejohn, Some Medico-Legal Aspects of Silicosis, 10 MEDICO-LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL REV. 78 (1942). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Safety measures to mitigate the risk of inhaling silica—wearing masks, proper ventilation, use of wet drilling techniques—were likewise widely know. Union Carbide and their contractors at Rinehart and Dennis knew of the risk of silicosis and how to prevent it.

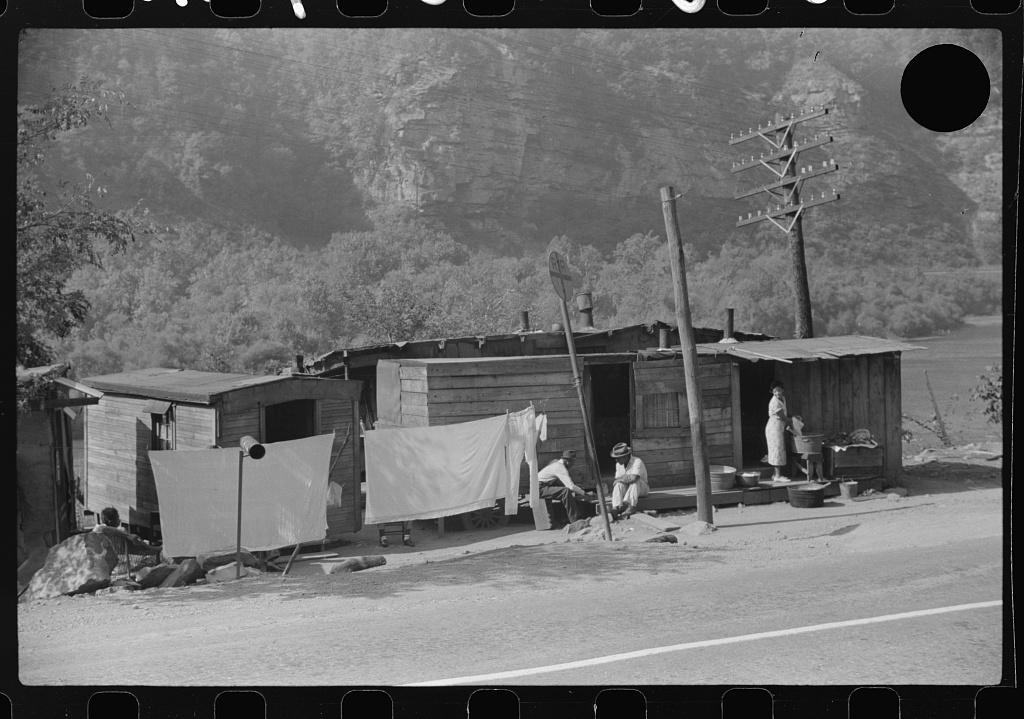

When workers began to die, no one in management was surprised. The company paymaster is reported to have said: “I knew they was going to kill [them] within five years, but I didn’t know they was going to kill [them] so quick.“[4]Vito Marcantonio. I Vote My Conscience (1956). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. The original text of this quote uses a racial slur to refer to the workers, reflecting the inherently racist character of the Hawk’s Nest disaster: the vast majority of workers digging the tunnel were Black men who had migrated north from the South in search of employment. The workers at Hawk’s Nest were essentially a captive labor force, housed in overcrowded and unfurnished shacks, with the Black workers paid not in currency but in company scrip, which could only be cashed (for a fee) at the company commissary.

Management treated these men, most of whom had no friends or family in the area, as disposable labor. Workers reported being forced into the tunnel at gunpoint. When workers became too ill to dig in the tunnels, the sheriff and his deputies—acting as de facto enforcers for Union Carbide—forced them out of town. George Robinson, a Black driller who worked in the tunnels, testified [5]Marc Galanter, Bhopals, Past and Present: The Changing Legal Response to Mass Disaster, 10 WINDSOR Y.B. ACCESS JUST. 151 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to this in 1936:

When it got so a worker couldn’t make it at all, when he got sick and simply couldn’t go longer, the sheriff would come around and run him off the place, off the works. I have seen the sheriff and his men run the workers off their places when they were sick and weak, so weak they could hardly walk. Some of them would have to stand up at the sides of trees to hold themselves up. And the sheriff and his men could plainly see that the men were sick and unable to go, yet they kept making them keep on the move…Many of the men died in the tunnel camps; they died in hospitals, under rocks and every place else.

Rinehart and Dennis completed the tunnel six months ahead of schedule, earning a substantial cash bonus. Over the course of 18 months of the project, nearly 3,000 men worked inside the tunnel. Of those men, at least 764 died from silicosis. Some estimates range as high as 2,000 dead.[6]Paul Stretesky & Michael J. Lynch, Corporate environmental violence and racism, 30 CRIME L. & SOC. CHANGE 163 (1999). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The company hired an undertaker to perform mass burials in unmarked graves at $50 a head.[7]Vito Marcantonio. I Vote My Conscience (1956). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. However, the records were mysteriously “lost” when news of the disaster began to come to light. The exact number of dead will almost certainly never be known.

Court Cases and Congressional Hearings

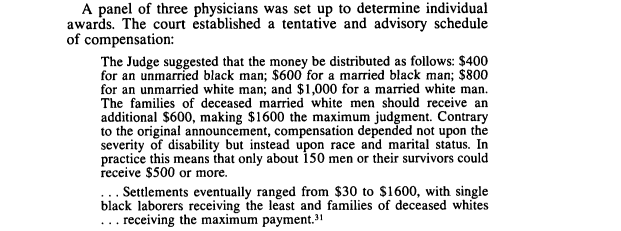

Despite the speed of the project, and Union Carbide’s best efforts to suppress news of the death toll—including offering what amounted to bribes to attorneys[8]Jack B. Weinstein, Secrecy in Civil Trials: Some Tentative Views, 9 J.L. & POL’y 53 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in exchange for promises not to file litigation—word got out. Dora Jones—whose husband, brother, and three sons all died after working in the tunnel—filed suit against Rinehart and Dennis in 1932, leading to a ruling by the West Virginia Supreme Court[9]Jones v. Rinehart, 113 W.Va. 414 (West Virginia 1933). This case can be found in Fastcase. that the company was liable for some worker’s compensation damages to survivors and the families of the dead. Even when compensation was eventually awarded, it was scaled according to the race of the recipient, with some disabled Black workers receiving as little as $30,[10]Marc Galanter, Bhopals, Past and Present: The Changing Legal Response to Mass Disaster, 10 WINDSOR Y.B. ACCESS JUST. 151 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. equivalent to a little under $550 in 2023.

As the press got hold of the story, word eventually made its was to federal officials. In 1936, more than four years after the completion of the tunnel, the House Committee on Labor heard testimony from survivors and other witnesses to the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster and its aftermath. The committee’s report[11]80 Cong. Rec. 4720 (1936). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. was damning.

The subcommittee finds that there was an utter disregard for all and any of these approved methods of prevention in the construction of this tunnel…[that] the whole driving of the tunnel was begun, continued, and completed with grave and inhuman disregard of all consideration for the health, lives, and future of the employees….The record presents a story of a condition that is hardly conceivable in a democratic government in the present century. It would be more representative of the Middle Ages.

Despite the conclusions of the House Committee, neither Rinehart and Dennis nor Union Carbide would ever face legal consequences for the Hawk’s Nest disaster. Fifty years later, Union Carbide would once again become infamous with the Bhopal chemical disaster, when an accident at a chemical plant in India killed as many as 16,000 people and caused over half a million injuries. As with Hawk’s Nest, Union Carbide faced no significant punishment for the disaster.

Incremental Reform

Although neither Rinehart and Dennis or Union Carbide, nor any of their employees, ever faced consequences for the deaths at Hawk’s Nest, the congressional hearings did serve as an impetus for incremental reform. Following the hearings, the House and Senate passed a joint resolution, which empowered Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins to convene the First National Silicosis Conference[12]Problems Relating to the Insolvency of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of the Committee on Ways and Means. 75 Cong. 127 (1981). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional … Continue reading in 1936. The findings of the conference, issued in report form in 1937, prompted many states to add silicosis to their list of diseases covered under worker’s compensation laws. However, differing definitions of the disease, exemptions for employers, and the lack of effective enforcement mechanisms meant that few workers ever received benefits.

The same year saw the passage of the Walsh-Healey Act,[13]To provide conditions for the purchase of supplies and the making of contracts by the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 74-846 / Chapter 881, 74 Congress. 49 Stat. 2036 (1919-1936) (1936). This document can be found in … Continue reading which established general health and safety standards for federal contractors. This was followed in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act,[14]To provide for the establishment of fair labor standards in employments in and affecting interstate commerce, and for other purposes., Public Law 75-718 / Chapter 676, 75 Congress. 52 Stat. 1060 (1938). This document can be found in … Continue reading which established a minimum wage, 40-hour work week, and mandated overtime pay for the majority of workers nationwide. However, nationwide safety regulations were slow to develop, in the face of widespread opposition from corporate interest groups. The most meaningful federal legislation on workplace safety, including the first federal guidelines for preventing silicosis, came in 1970 with the passage of the Occupational Health and Safety Act[15]To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women, by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; … Continue reading which, crucially, provided a means for the enforcement of regulations with the establishment of the Occupational Health and Safety Administration. The original 1971 guidelines on airborne silica were updated for the first time,[16]81 Fed. Reg. 16286 (2016), Friday, March 25, 2016, pages 16053 – 16283. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. in the face of sustained opposition from industry lobbyists, in 2016.

The Book of the Dead

In 1938, two years after the hearings in Congress, the journalist and poet Muriel Rukeyser travelled from New York to the town of Gauley Bridge. Rukeyser had been active in progressive politics throughout her career, even attracting the attention of the FBI and the House Special Committee on Unamerican Activities[17]Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activity in the United States. Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, 75 Cong. 557 (1938). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. for her activism. Rukeyser travelled to Gauley Bridge to talk firsthand with survivors of the Hawk’s Nest disaster. She recorded their recollections in The Book of the Dead, a groundbreaking work that combined poetry with investigative journalism, and remains to this day one of the best accountings of the disaster. In George Robinson: Blues, she sets the testimony of driller George Robinson to verse, painting an evocative picture of the eerie and apocalyptic environment of the tunnel and town of Gauley Bridge, choked with white dust:

When the blast went off the boss would call out, Come, let’s go back,

when that heavy loaded blast went white, Come, let’s go back,

telling us hurry, hurry, into the falling rocks and muck.The water they would bring had dust in it, our drinking water,

the camps and their groves were colored with the dust,

we cleaned our clothes in the groves, but we always had the dust.

Looked like somebody sprinkled flour all over the parks and groves,

it stayed and the rain couldn’t wash it away and it twinkled

that white dust really looked pretty down around our ankles.As dark as I am, when I came out at morning after the tunnel at night,

with a white man, nobody could have told which man was white.

The dust had covered us both, and the dust was white.

Rukeyser’s work in The Book of the Dead and elsewhere continued to earn her the attention of the FBI and Special Committee on Unamerican Activities well into the 1950s. Rukeyser’s work is carried on through the present day with the Hawk’s Nest Names project, which seeks to collect the names, death certificates, and stories of the men who worked and died in Gauley Bridge.

Further Reading

HeinOnline has an entire collection dedicated to the study of labor and employment law and working class history: Labor & Employment: The American Worker. Some noteworthy features of the collection are a catalog of landmark cases in labor law, numerous federal hearings and reports, and an interactive timeline of labor history.

To make sure you keep receiving updates on new content and deep dives into the archives, consider subscribing to our blog, so you never miss a post.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Jessica L. Toler, Dead Canaries: The Struggle of Appalachian Coal Miners to Get Black Lung Benefits, 6 J. GENDER RACE & JUST. 163 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4, ↑7 | Vito Marcantonio. I Vote My Conscience (1956). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Spinelli’s Law Library Reference Shelf. |

| ↑3 | A. Meiklejohn, Some Medico-Legal Aspects of Silicosis, 10 MEDICO-LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL REV. 78 (1942). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5, ↑10 | Marc Galanter, Bhopals, Past and Present: The Changing Legal Response to Mass Disaster, 10 WINDSOR Y.B. ACCESS JUST. 151 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | Paul Stretesky & Michael J. Lynch, Corporate environmental violence and racism, 30 CRIME L. & SOC. CHANGE 163 (1999). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Jack B. Weinstein, Secrecy in Civil Trials: Some Tentative Views, 9 J.L. & POL’y 53 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9 | Jones v. Rinehart, 113 W.Va. 414 (West Virginia 1933). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑11 | 80 Cong. Rec. 4720 (1936). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |

| ↑12 | Problems Relating to the Insolvency of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of the Committee on Ways and Means. 75 Cong. 127 (1981). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |

| ↑13 | To provide conditions for the purchase of supplies and the making of contracts by the United States, and for other purposes., Public Law 74-846 / Chapter 881, 74 Congress. 49 Stat. 2036 (1919-1936) (1936). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |

| ↑14 | To provide for the establishment of fair labor standards in employments in and affecting interstate commerce, and for other purposes., Public Law 75-718 / Chapter 676, 75 Congress. 52 Stat. 1060 (1938). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |

| ↑15 | To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women, by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health, and for other purposes., Public Law 91-596, 91 Congress. 84 Stat. 1590 (1970). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |

| ↑16 | 81 Fed. Reg. 16286 (2016), Friday, March 25, 2016, pages 16053 – 16283. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |

| ↑17 | Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activity in the United States. Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, 75 Cong. 557 (1938). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents collection. |