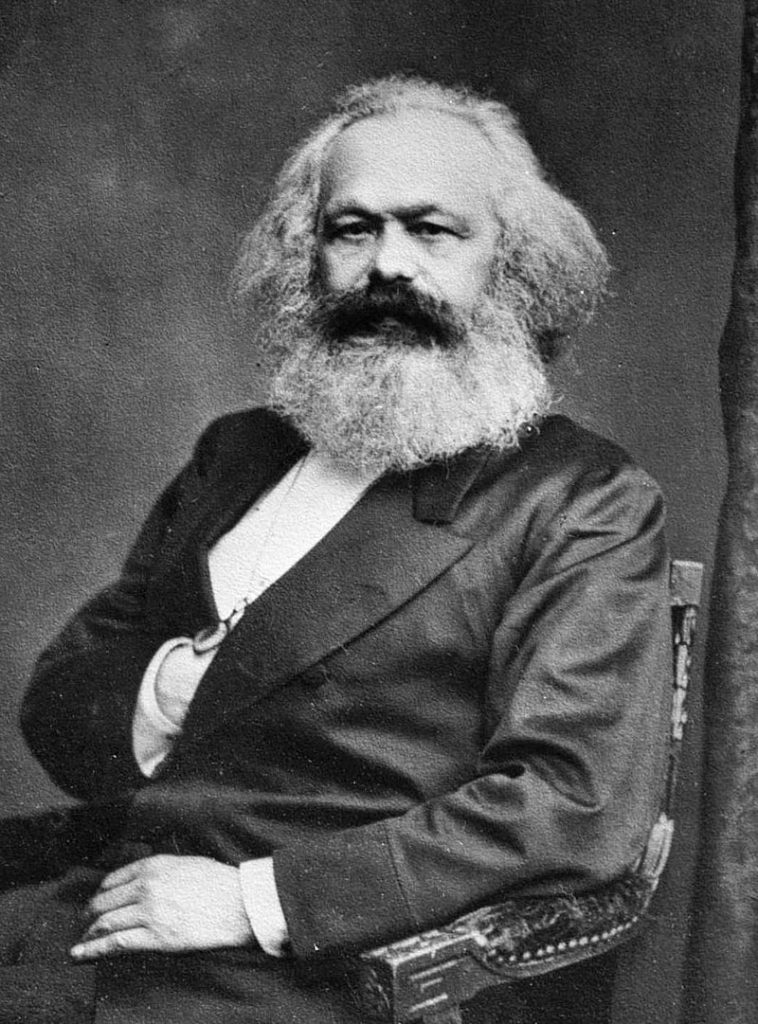

German philosopher and socialist Karl Marx had a profound impact on history, sociology, politics, and economics. He may not have seen much of this influence within his lifetime—he died poor, stateless, widowed, and in ill health in 1883—but his ideas and his writings, particularly The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital, would serve as inspiration for various revolutions throughout the 20th century.

With the help of HeinOnline, let’s take a look at Karl Marx’s life, philosophy, and legacy.

A Mischievous Youth

Marx was born in Trier, Prussia to Heinrich and Henrietta Marx in 1818. He would be the oldest surviving son of nine children. Heinrich Marx was a lawyer and heavily inspired by Enlightenment figures such as Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. Both Heinrich and Henrietta were Jewish, but they converted to Christianity later in life, likely for professional reasons,[1]Paul van Warmelo, Karl Marx, 50 THRHR 19 (1987). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and had Karl baptized as Christian as well.

Karl’s high school was run by a liberal principal who was friends with Heinrich and drew suspicion from local police forces, who raided the school in 1832. Karl then began studying humanities at the University of Bonn, where he was generally a troublemaker—he was arrested for drunkenness and participated in a duel, among other schemes. His father encouraged him to transfer to the more academic University of Berlin, where Karl would study law and philosophy.

Radical Roots & Introduction to Hegelianism

At the University of Berlin, Marx would join a radical group called the Young Hegelians,[2]Andrew Vincent, Marx and Law, 20 J.L. & SOC’y 371 (1993). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. who were inspired by the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Other members of this group included other left-wing thinkers such as Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Feuerbach. However, Marx’s academics suffered during this time, and the Prussian government was cracking down on radicals at the university, so he submitted his doctoral thesis, titled The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, to the University of Jena and received his degree from there.

Marx was unable to continue pursuing academia due to his left-wing beliefs, so he began working in journalism, writing for a variety of radical newspapers starting with Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland News)[3]G. D. H. Cole. History of Socialist Thought (1967). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. in Cologne in 1842. These writings would establish his early views on socialism. However, the newspaper was censored by the Prussian government and was eventually banned in 1843.

Marx & Engels

Marx became co-editor for Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals) and moved to Paris with his new wife, Jenny von Westphalen, to whom he had been engaged for several years. It was while working on this short-lived paper that he met German socialist Friedrich Engels at a cafe on August 28, 1844. Their friendship would prove to shape Marx’s career. Engels had spent time in England observing the working class struggle there and in his publication The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 posited that it would be the working class that would lead an emancipatory revolution.

While working on another newspaper, Vorwärts! (Forward!), Marx was expelled from Paris and moved to Brussels, Belgium. There, he and Engels published Die Heilige Familie (The Holy Family)[4]Paul van Warmelo, Karl Marx, 50 THRHR 19 (1987). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. which was a critique of the idealism of Hegel—Marx believed that Hegel’s philosophy was too based on spirit and ideas, where he and Engels believed that true change could only come from material action. During this time, Marx also wrote The German Ideology[5]John A. Gueguen, Origins: Karl Marx on Justice and Law, 14 PERSONA & DERECHO 279 (1986). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and Theses on Feuerbach,[6]Paul Thomas, Karl Marx and Max Stirner, 3 POL. THEORY 159 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. but he couldn’t find a publisher so these works wouldn’t be published until after his death.

The Communist Manifesto

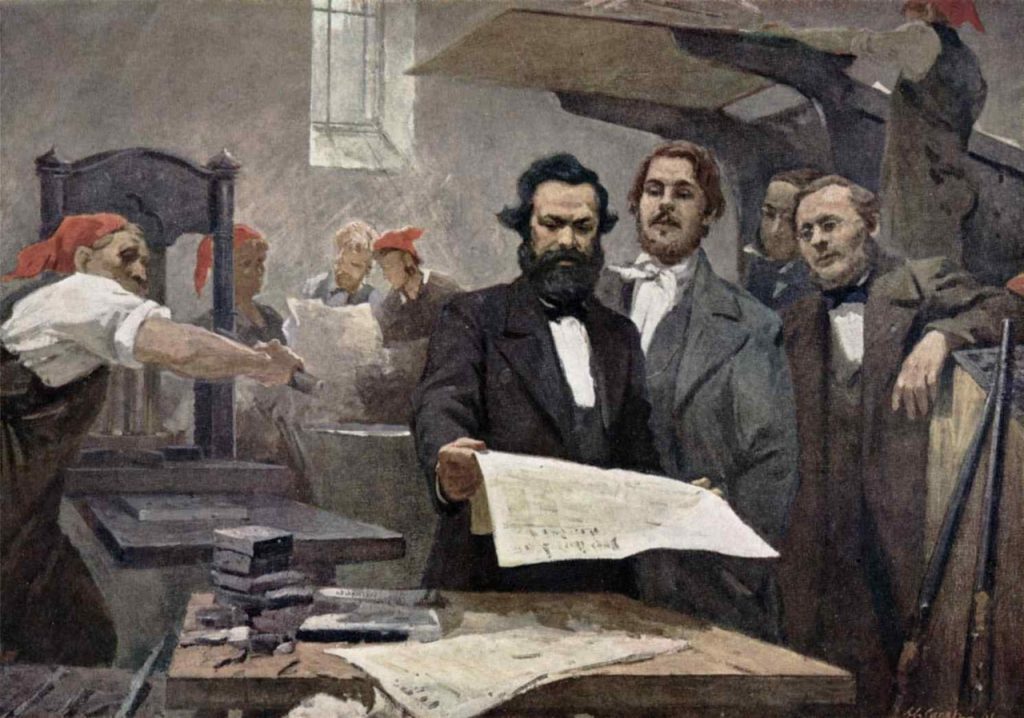

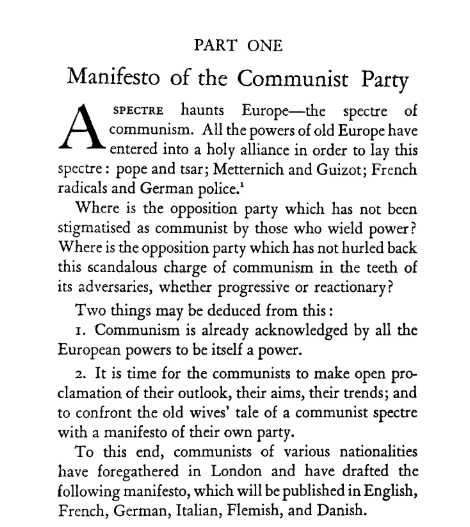

Marx was part of a secret radical group called the League of the Just,[7]Charles Seignobos. Political History of Europe since 1814 (1907). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. which he believed could actually have the power to spur the working class into a mass movement if it became an open political party. Thus, it came out from the underground and became a public society called the Communist League in 1847. To help establish the goals and beliefs of the group, Marx wrote and published one of his most well-known and widely read works, The Communist Manifesto,[8]Karl; et al. Marx. Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. on February 21, 1848. The opening line of the pamphlet reads, “This history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” It goes on to describe 10 immediate steps to transitioning the country to communism, with ideas such as free education for children, a progressive income tax, and the abolishment of inheritance. It ends with the statement. “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries, unite!”

1848 also brought a wave of revolutions[9]Charles F.; et al. Horne. Great Events by Famous Historians: A Comprehensive and Readable Account of the World’s History, Emphasizing the More Important Events, and Presenting These as Complete Narratives in the Master-Words of the Most … Continue reading across Europe, including in Italy, Austria, and France. Particularly in France, the proletariat overthrew the monarchy and established the short-lived French Second Republic. Marx moved back to France under this revolutionary government when he was expelled from Belgium for suspicions of funding local revolutionaries. However, he was expelled from France, as well as kicked out of Belgium when he tried to return there, so finally he moved with his wife to London, where he would live for the rest of his life—although he would never be granted citizenship.

Struggles and Successes

The Communist League was not long-lasting. Tensions began to develop within the group because some members wanted to take immediate action and start a working class revolution, while Marx and Engels believed that more time was needed to gain the support of the liberal bourgeoise. Additionally, at this time, Marx was struggling financially. His only source of income was publishing articles for the New-York Daily Tribune,[10]Brian L. Frye, Karl Marx, Literary Landlord, 25 VA. J.L. & TECH. 279 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. which was edited by Charles A. Dana and Horace Greeley. He wrote for the paper until it changed editorial hands in 1863. Marx relied on Engels to support him financially.

In 1864, Marx became involved with the International Workingmen’s Association,[11]John Rogers; et al. Commons. History of Labour in the United States (1966). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. also known as First National, a group which worked successfully on behalf of several European trade unions and would eventually grow to a membership of 800,000. However, this group would also eventually disband, as a faction led by Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin[12]David J. Saposs, The Impact of Labor Ideology on Industrial Relations, 85 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 1100 (1962). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. disagreed with Marx and Engels that cooperation with the Liberal Party was necessary for the success of trade unions.

During his time with First International, the Paris Commune of 1871[13]Glen Shortliffe, Class Conflict and International Politics, 4 INT’l J. 95 (1949). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. represented, according to Engels, the first “dictatorship of the proletariat.” During the Franco-Prussian War, working-class members of the National Guard revolted against the Third Republic and overtook the city for two months, instilling a socialist style of government. However, they were violently suppressed by the French army, and potentially as many as 20,000 Communards were killed.

Das Kapital

Marx’s philosophy is best demonstrated in his life’s work, Das Kapital. The text consists of three volumes, only the first of which was published in Marx’s lifetime, in 1867—Engels published the second two volumes after Marx’s death. In the text, Marx describes his theory that capital is created through the exploitation of the laboring classes, whose unpaid work creates surplus value that benefits the owning classes. According to Marx, the very nature of capitalism will lead to its collapse—eventually, the working class will engage in a revolution and establish a communist government, through which the proletariat will take ownership of industry and production.

Das Kapital was translated into all major languages. The English translation was first published in 1887 as Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production.[14]Karl; et al. Marx. Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (1889). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database.

Death and Influence

Marx suffered from poor health throughout his life, including depression and liver issues which were exacerbated by heavy drinking, excessive work, and chronic insomnia. Towards the end of his life, he also experienced painful welts on his skin. He passed away from bronchitis and pleurisy on March 15, 1883, two years after his wife died. He was buried at Highgate Cemetery, and his tomb was later inscribed with the last line from The Communist Manifesto, “Workers of all Lands United,” as well as the phrase “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways—the point however is to change it,” from his Thesis on Feurerbach.

Marx’s work was influential in various revolutions throughout the 20th century, such as the Russian Revolution[15]Basil Thomson. My Experiences at Scotland Yard (1923). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. which established the Soviet Union. Various political leaders were also influenced by Marx, such as Nelson Mandela, Fidel Castro, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Research the Greatest Minds in History in HeinOnline

Did you know that HeinOnline has books and texts from some of the minds that have shaped history? Our Legal Classics and World Constitutions Illustrated databases contain thousands of titles such as Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, and also:

- Leviathan, Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth by Thomas Hobbes

- The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt

- On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

- Philosophy of Law by Immanuel Kant

- The Republic by Plato

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine

- And many more!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Paul van Warmelo, Karl Marx, 50 THRHR 19 (1987). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Andrew Vincent, Marx and Law, 20 J.L. & SOC’y 371 (1993). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | G. D. H. Cole. History of Socialist Thought (1967). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. |

| ↑4 | Paul van Warmelo, Karl Marx, 50 THRHR 19 (1987). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | John A. Gueguen, Origins: Karl Marx on Justice and Law, 14 PERSONA & DERECHO 279 (1986). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | Paul Thomas, Karl Marx and Max Stirner, 3 POL. THEORY 159 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | Charles Seignobos. Political History of Europe since 1814 (1907). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑8 | Karl; et al. Marx. Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑9 | Charles F.; et al. Horne. Great Events by Famous Historians: A Comprehensive and Readable Account of the World’s History, Emphasizing the More Important Events, and Presenting These as Complete Narratives in the Master-Words of the Most Eminent Historians (1905). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. |

| ↑10 | Brian L. Frye, Karl Marx, Literary Landlord, 25 VA. J.L. & TECH. 279 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | John Rogers; et al. Commons. History of Labour in the United States (1966). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. |

| ↑12 | David J. Saposs, The Impact of Labor Ideology on Industrial Relations, 85 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 1100 (1962). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13 | Glen Shortliffe, Class Conflict and International Politics, 4 INT’l J. 95 (1949). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14 | Karl; et al. Marx. Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production (1889). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑15 | Basil Thomson. My Experiences at Scotland Yard (1923). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |