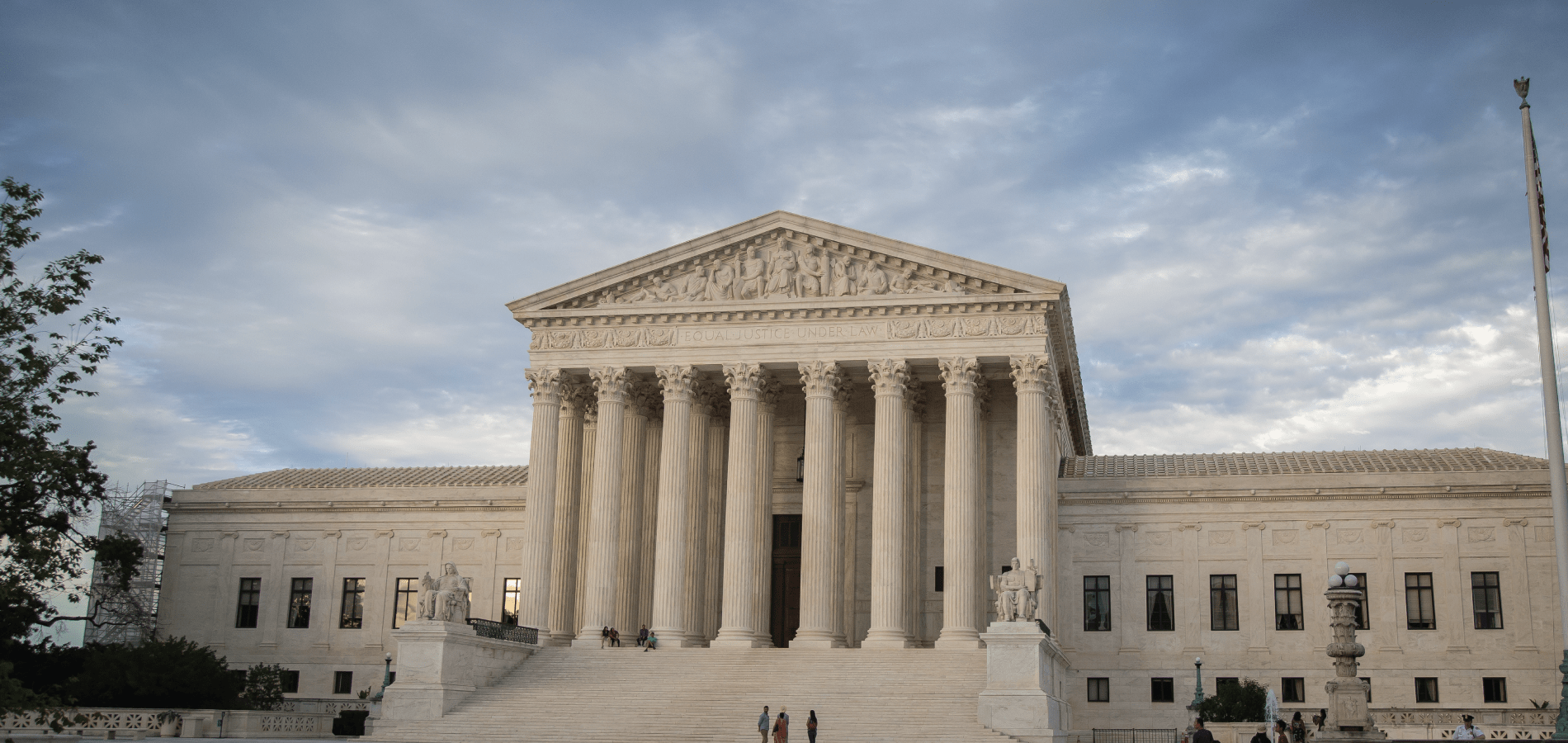

We here in America celebrated our national holiday, Independence Day, on July 4. Ten days later, on July 14, France celebrates its own national holiday, called Bastille Day, or Fête nationale française. While America’s holiday celebrates the signing of the Declaration of Independence, France’s holiday celebrates an event that some consider to be the starting point of the French Revolution: the storming of the Bastille fortress in Paris. What sparked this event, and why is it still celebrated more than 230 years later? Let’s dive into HeinOnline to find out.

Battle of the Classes

During the late 18th century, the differences in quality of life between the social classes were stark.[1]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. King Louis XVI was known for his extravagant spending and lavish lifestyle, while the peasantry suffered under high taxes, exorbitant bread prices, and meager harvests due to drought, leading to riots and strikes. To avoid economic upheaval and further violence, the King summoned together the Estates General—a group of clergy, nobility, and the middle class—to encourage them to support his new financial package, which would force the aristocracy to participate in a universal land tax.[2]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database.

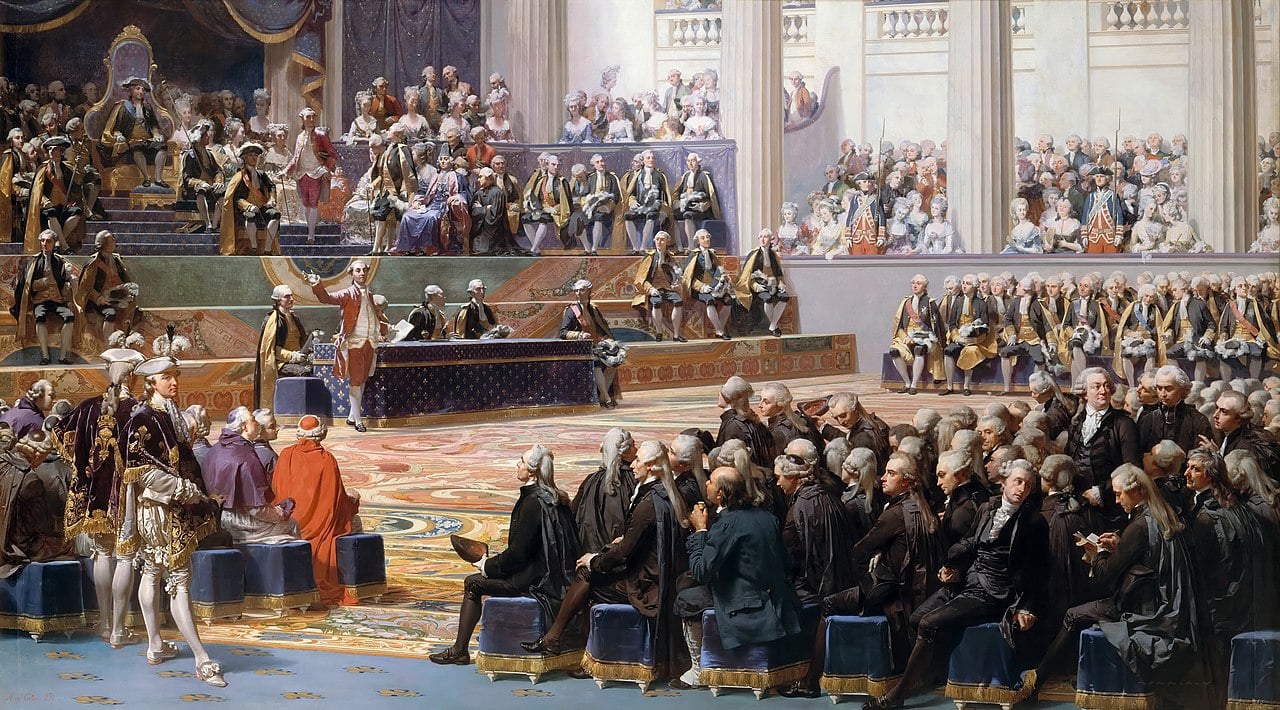

The Estates General had not been called together for 170 years, and much had changed since then—particularly, the middle class, or the Third Estate, now consisted of about 98% of the Estates General, but they could still be outvoted by the other two Estates.[3]Sophia H. MacLehose. From the Monarchy to the Republic in France, 1788-1792 (1904). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. Angered by the lack of fair representation,[4]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. they organized to advocate for power based on numbers rather than wealth. These tensions led to a hostile meeting of the Estates General at Versailles in early May 1789.

Let’s Go Down to the Tennis Court

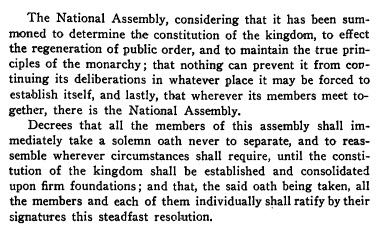

The Third Estate, led by Parisian scientist Jean Sylvain Bailly,[5]Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. named themselves the National Assembly.[6]Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. On the morning of June 20, upon finding themselves locked out of the meeting hall at Versailles and convinced that the king and the other two Estates were conspiring against them, the National Assembly met at a nearby indoor tennis court. Here, they pledged what would be called the Tennis Court Oath,[7]Frank Maloy Anderson. Constitutions and Other Select Documents Illustrative of the History of France, 1789-1907 (1908). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. “never to separate, and to reassemble wherever circumstances shall require, until the constitution of the kingdom shall be established and consolidated upon firm foundations…”

King Louis XVI, fearing retribution, finally agreed to join all of the Estates together into a new National Assembly.

Panic at the Bastille

On July 11, 1789, Louis XVI fired his financial minister, Jacques Necker, who was sympathetic to the Third Estate and the National Assembly, and replaced his ministry with conservative elites. Fearing a coup, Parisians began to panic. Camille Desmoulins,[8]Mayo W. Hazeltine, Editor. Orations from Homer to William McKinley (1902). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. a journalist and politician, sparked a crowd to action[9]Sophia H. MacLehose. From the Monarchy to the Republic in France, 1788-1792 (1904). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. with an impassioned speech.

Public demonstrations erupted, with the king’s armies attempting to fight back. A militia of nearly 50,000 members of the bourgeoisie, called the National Guard, was established to attempt to bring order to the city.

The Bastille, an armed fortress and political prison that on July 14 only held seven prisoners, represented to the Third Estate the shackles of royal oppression.[10]Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. It also housed gunpowder and weapons. A crowd of rebels gathered outside the guarded Bastille. The guards and citizens negotiated for access, but the crowd grew inpatient and eventually broke into the courtyard. As the crowd flooded into the Bastille, gunshots rang out, which turned the chaos into a vicious battle. The French Guard,[11]Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. sympathetic to the popular cause, joined the stormers. The commander of the Bastille, Governor de Launay,[12]Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. seeing his troops depleted, eventually gave in, and the Parisians overtook the fortress, freeing the prisoners along the way. During the storming, nearly 100 people died, including de Launay.

The First Fight of the Revolution?

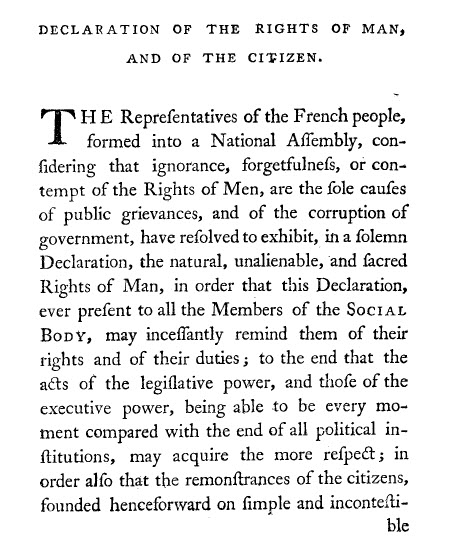

Some historians consider the storming of the Bastille the beginning of the French Revolution, which was the period of intense social upheaval that lasted through the 1790s until the rise to power of Napoleon Bonaparte. Closely following the riot in Paris, panic spread throughout the French countryside as peasants and townspeople began to attack the residences of the aristocracy. This period was called The Great Fear,[13]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. or la Grande Peur. On August 4, the National Constituent Assembly officially abolished feudalism in France. And on August 26, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen[14]English translation of the French original text of the Declaration of 1789 15 (2013) Declaration of the Rights of Man, and of the Citizen as a first step toward a national constitution. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World … Continue reading The document, inspired by Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire[15]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. and Jean Jacques Rousseau,[16]James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. outlined the values of the French Revolution, including liberty and democracy.

A National Celebration

On the one year anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, a great celebration was held in France, called the Fête de la Fédération, to commemorate the first steps toward the abolishment of the Old Regime. However, after this first celebration, July 14 wasn’t really acknowledged as a holiday anymore until the French Parliament passed an act in 1880 that would make the day a national holiday.[17]Blandine Chelini-Pont, Is Laicite the Civil Religion of France, 41 GEO. WASH. INT’l L. REV. 765 (2010). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Now, on Bastille Day, there is a military parade on the Champs-Elysées, as well as fireworks displays and other celebrations similar to those held on America’s Independence Day.

Storming Your Inbox

Well, not really, but you can subscribe to the HeinOnline Blog to get posts just like this one delivered straight to your inbox so you never miss a database update, new feature, or fascinating story from history. We’ll see you with the next one!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑13, ↑15, ↑16 | James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | Sophia H. MacLehose. From the Monarchy to the Republic in France, 1788-1792 (1904). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑4 | James Harvey Robinson. Introduction to the History of Western Europe: With Supplement (1918). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑5, ↑6, ↑10, ↑11, ↑12 | Cornwell B. Rogers. Spirit of Revolution in 1789 (1949). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑7 | Frank Maloy Anderson. Constitutions and Other Select Documents Illustrative of the History of France, 1789-1907 (1908). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑8 | Mayo W. Hazeltine, Editor. Orations from Homer to William McKinley (1902). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. |

| ↑9 | Sophia H. MacLehose. From the Monarchy to the Republic in France, 1788-1792 (1904). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑14 | English translation of the French original text of the Declaration of 1789 15 (2013) Declaration of the Rights of Man, and of the Citizen as a first step toward a national constitution. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑17 | Blandine Chelini-Pont, Is Laicite the Civil Religion of France, 41 GEO. WASH. INT’l L. REV. 765 (2010). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |