Since the nineteenth century, Niagara Falls has attracted tourists from across the world, who are drawn to its natural wonders and hospitality. Before the American Civil War, it was also a major hub on the Underground Railroad. Keep reading to learn more about the Cataract House, a luxury hotel in Niagara Falls whose staff were secret agents of the Underground Railroad and ferried dozens of people fleeing slavery to freedom in Canada.

The Cataract House

Throughout the nineteenth century, Niagara Falls was a popular destination for wealthy white Southern tourists. Before the Civil War, many of these Southern tourists travelled with the people they enslaved accompanying them, recording them as “servants” in the guest logs of the hotels that accommodated them. New York was a free state, where slavery had been illegal since 1827.[1]An Act for the gradual abolition of slavery. Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature (1797-1800). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library collection. For these “servants,” a visit to Niagara Falls presented a unique opportunity.

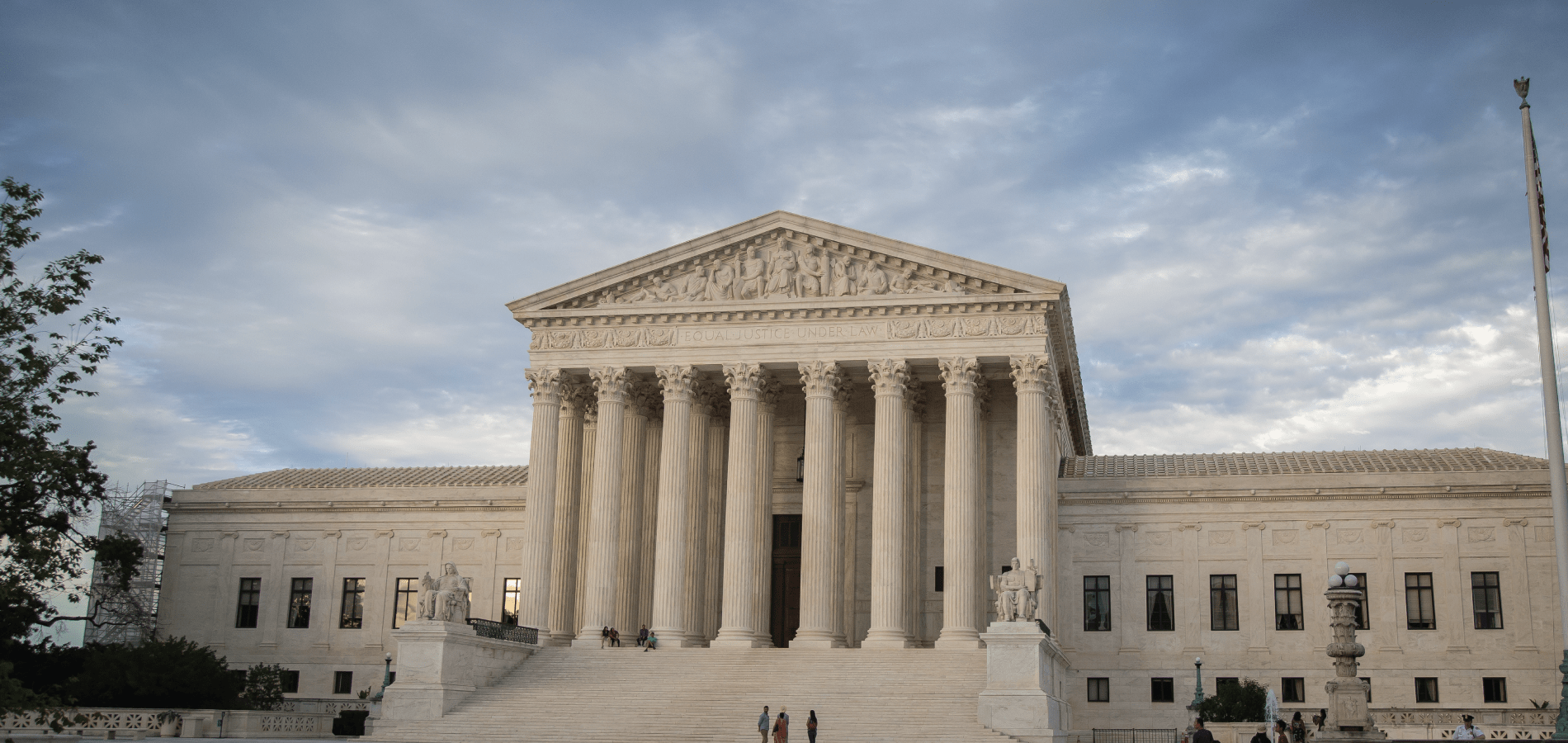

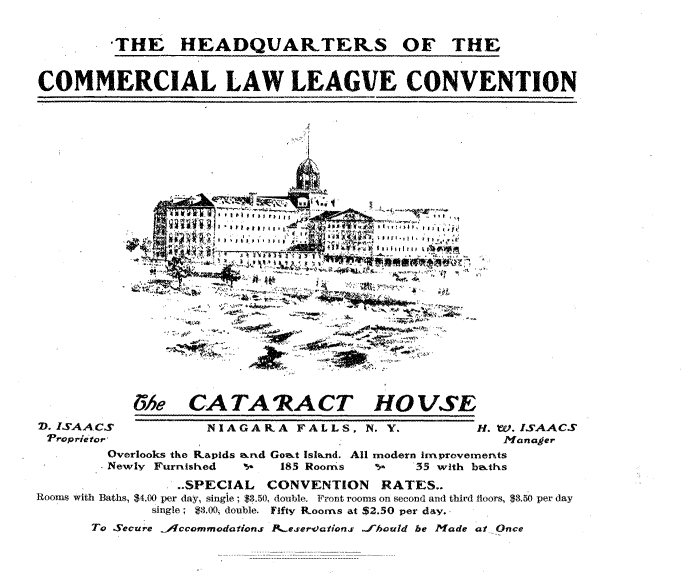

One of the most famous and glamorous hotels in Niagara Falls was the Cataract House. Between its construction in 1825 and its destruction by fire in 1945, the Cataract House hosted thousands of guests, including such celebrities and political figures as Abraham Lincoln and two separate Kings of England (although one was a prince at the time). The Cataract House was an impressive building, originally constructed in the neoclassical Federal style, and expanded upon with a series of renovations. It contained hundreds of guest rooms (many with their own baths, a luxury for the time!), fine dining rooms, and ballrooms.

But the Cataract House was not merely a luxury hotel. It was also a major stop on the Underground Railroad whose staff helped dozens of enslaved people escape across the Niagara River to Canada. From the back door of the Cataract House, Canada—and the freedom it offered people fleeing enslavement—was only eight minutes away for a boat with a skilled oarsman.

Niagara Falls and the Underground Railroad

The wealthy white owners of the Cataract House were quiet sympathizers with the abolitionist cause. In the 1840s and 1850s they employed almost exclusively Black men in the dining rooms and kitchens of their hotel. These men, many of whom had escaped enslavement in the South, have come to be known as the “Secret Agents of the Underground Railroad.”

Accounts of Underground Railroad activity at the Cataract House can be found as early as 1841, when a slave owner lamented in a letter to the New Orleans Times-Picayune that waiters at the Cataract House had helped his “servant,” a fourteen-year-old girl, escape across the river to Canada. Unable to believe that she had chosen to escape of her own volition, he pursued her to Canada where he discovered that she very much did not wish to return with him. He was chased off by the free Black population of the Canadian side and returned to New York empty-handed. He warned Southerners visiting Niagara Falls to avoid the Cataract House, as “the proprietors…keep in their employ, as servants, a set of free negroes, many of whom have wives and relatives in Canada, and they have an organized plan of taking off all slaves that come to the house.”[2]The full text of the letter can be viewed as part of the excellent exhibit, One More River to Cross, at the Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center in Niagara Falls, NY. He advised Southerners visiting the Falls to instead stay at the Eagle Hotel, whose owners were not abolitionists.

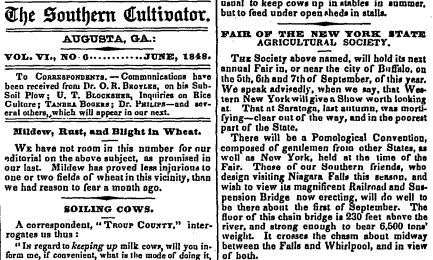

Despite these warnings, Niagara Falls continued to be a popular destination for Southern tourists, with pro-slavery publications recommending the Falls as a place of interest for those visiting the North. For instance, this bulletin[3]Fair of the New York State Agricultural Society. 6 S. Cultivator 81 (1848). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. in an 1848 issue of The Southern Cultivator, a pro-slavery newspaper, recommends that “Southern friends” attending an agricultural convention in Buffalo pay a visit to Niagara Falls to view the construction of the international railway suspension bridge to Canada. Intriguingly, the author expresses some reservations about attending the convention, indicating that the previous year’s event in Saratoga was “mortifying.”

Thwarted Rescues and Daring Escapes

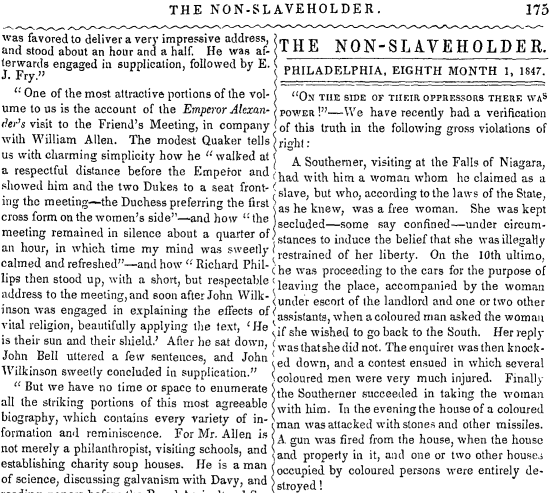

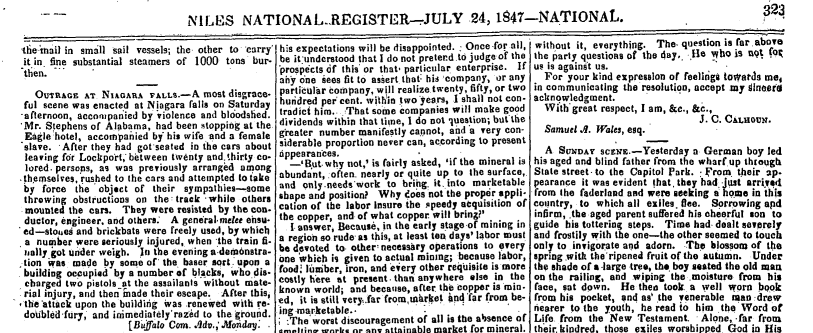

Intriguing, and occasionally conflicting, accounts of the escapades of the staff of the Cataract House are scattered throughout the newspapers of the time. One particularly noteworthy incident, which was widely reported, was the attempted rescue of an unnamed young woman in 1847. As The Non-Slaveholder—an abolitionist newspaper active in the years prior to the American Civil War—reported, a local free Black man approached the young woman as she (escorted by her captors) was preparing to board a train back South. He asked her if she wanted to go back to the South. She replied that she did not.[4]2 The Non-Slaveholder (Abm. L. Pennock, et al.) 169 (1847). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. One of the woman’s captors assaulted the man, pushing him to the ground. A brawl then broke out, as dozens of workers rushed out of the Cataract House and nearby businesses to try to rescue the woman. They fought with the woman’s captors, engineers on the train, and bystander who intervened on the other side, pelting them with stones and bricks. Tragically, the young woman was forced on to the train, which was able to depart the station. She was not heard from again.

The violence continued later that evening when a white mob descended upon the Black quarter of Niagara Falls, attacking a local Black-owned grocery store. The people inside the store fired on the crowd with pistols, allowing them to escape. Further enraged, the mob rioted and set fire to the building and other Black-owned properties in town.

Despite the danger, the staff of the Cataract House were undaunted in their efforts to ferry fugitives to freedom. They were well-organized and connected to an international network of informants in the Underground Railroad network. Oftentimes, word would reach the waitstaff ahead of time about the impending arrival of an enslaved person who wished to escape. One such case was documented in 1846, when Cecelia Jane Reynolds, a young girl enslaved by a wealthy Kentucky family, secretly informed an Underground Railroad operative in Louisville of her desire to escape to Canada. Word was passed through networks of Black workers employed on Great Lakes freighters, first reaching Toronto and then Niagara Falls. When Cecelia arrived at the Cataract House in May 1846, the waitstaff was ready and waiting to ferry her across the river. Two days after her arrival, Cecelia escaped to Canada, ultimately settling in Toronto.

In 1853, the case of Patrick Sneed attracted the attention of the national press. Sneed, who had escaped from enslavement in 1849, was working as a waiter at the Cataract House in August 1853, when two armed marshals arrested him—not for escaping slavery, but for charges of murder. Waiters at the Cataract House rushed to Sneed’s aid and fought with the police and a mob of white vigilantes. Despite their efforts, however, Sneed was ultimately taken into custody.

Sneed did not deny escaping enslavement, but he denied the charges of murder. Using his wages from his job at Cataract House, he hired a lawyer and filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus[6]The Fugitive Slave Law, and Its Victims. 1 Anti-Slavery Tracts 1 (1855-1856). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. before a judge in Buffalo. Sneed and his lawyer produced convincing evidence that the murder charges against him were a fabrication and, in September, Sneed was found innocent and released. He immediately departed for Canada.

It is certain that the written evidence of the exploits of the Cataract House staff represents only a small fraction of successful escapes. In fact, continued success meant ensuring that the Cataract House and its staff stayed out of the news as much as possible. The waiters at the Cataract House continued quietly ferrying people to freedom up until the very start of the American Civil War, as evidenced by the account of Rachel Smith, a Quaker and abolitionist who visited Niagara Falls in 1859. The head waiter, John Morrison,[7]R. C. Smedley. History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania (1883). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. approached Smith and indicated that he knew her father, whose home was a stop on the Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania.

Smith indicated that during her stay Morrison “ferried some across the river during two of the nights she was there.”

Legacy of the Cataract House

Following the end of the American Civil War, the Cataract House ceased to function as a stop on the Underground Railroad. However, it remained an important part of the cross-border Black community on the Niagara frontier until the turn of the twentieth century, when the practice of hiring Black waiters declined in Northern hotels and resorts.

The Cataract House was gutted by a fire in 1945, and demolished entirely in 1946. The site where it once stood is now part of Niagara Falls State Park. In recent years, researchers at the University at Buffalo have undertaken a number of archaeological studies of the area.

Further Research

HeinOnline has an entire collection devoted to the study of the institution of slavery and the continuing impact of the practice upon the contemporary world: Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture, and Law. The database is included in all core HeinOnline subscriptions, and is also available free of charge to any interested organizations and individuals as part of our Social Justice Suite.

If you are local, or happen to be visiting the Falls, you should pay a visit to the Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center. Their thoughtfully curated and impactful exhibit, One More River to Cross, provided valuable information and inspiration for the research that went into this post.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | An Act for the gradual abolition of slavery. Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature (1797-1800). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library collection. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The full text of the letter can be viewed as part of the excellent exhibit, One More River to Cross, at the Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center in Niagara Falls, NY. |

| ↑3 | Fair of the New York State Agricultural Society. 6 S. Cultivator 81 (1848). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. |

| ↑4 | 2 The Non-Slaveholder (Abm. L. Pennock, et al.) 169 (1847). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. |

| ↑5 | Outrage at Niagara Falls. 72 NILES’ NAT’l REG. 321 (1847). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | The Fugitive Slave Law, and Its Victims. 1 Anti-Slavery Tracts 1 (1855-1856). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. |

| ↑7 | R. C. Smedley. History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania (1883). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World collection. |

| ↑8 | 6 BULL. COM. L. LEAGUE AM. 1 (1902). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |