This year is the 100th anniversary of one of the United States’ most solemn monuments, the Tomb of the Unknown Solider at Arlington National Cemetery. The marble tomb, containing the bodies of three unidentified American servicemen, has remained continuously guarded since 1937 and serves as a poignant reminder of all those American servicemen and women who have given their lives for their country—and never returned home. In honor of this memorial’s monumental anniversary, let’s learn more about the Tomb with HeinOnline. We’ll be using resources from several HeinOnline databases to research this memorial, so make sure you are subscribed to the following to see all the content we’ve discovered:

- History of International Law

- Law Journal Library

- Military and Government

- U.S. Congressional Documents

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- U.S. Presidential Library

- U.S. Statutes at Large

- U.S. Treaties and Agreements

They Shall Not Grow Old

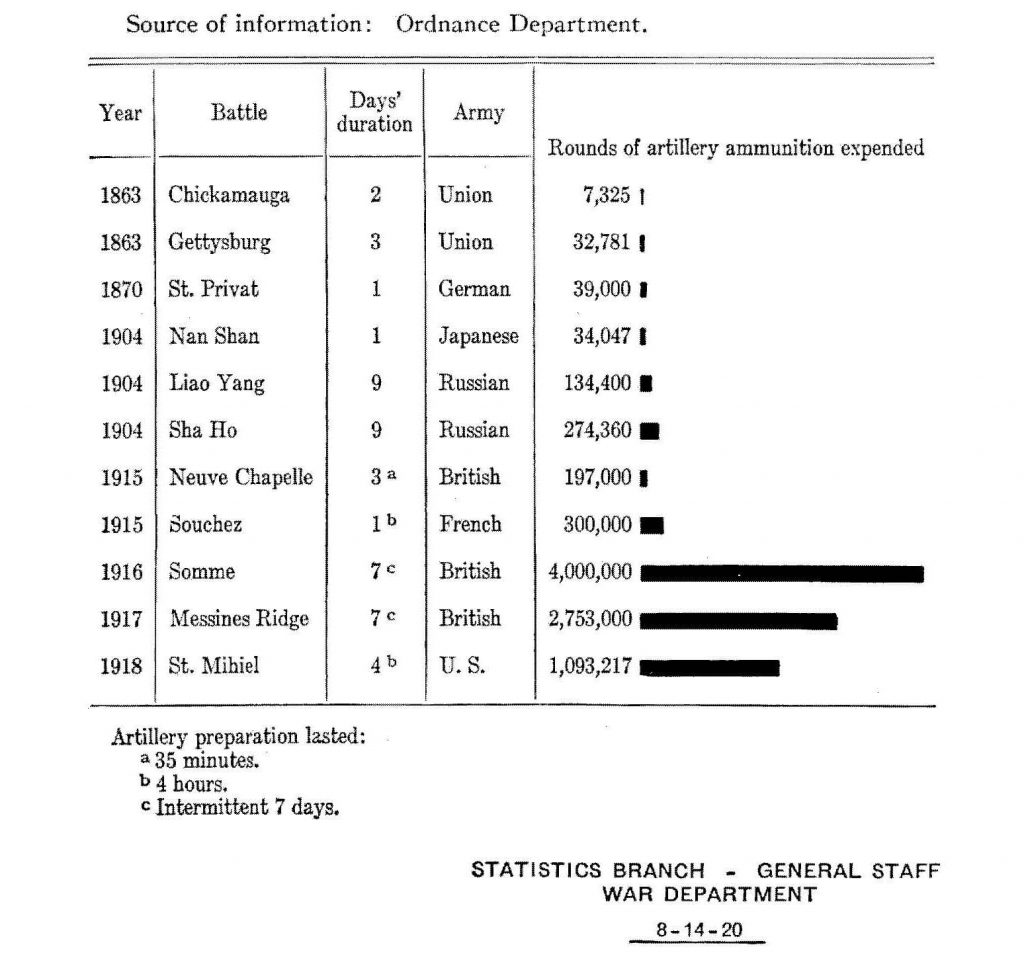

World War I’s destruction is almost incomprehensible: within four years, 15 to 22 million people—both military personnel and civilians—were killed, and approximately 20 million more were wounded. France mobilized 8.4 million men to fight; at the end of the war, 6 million of them were either dead, wounded, or missing. Russia mobilized 12 million; over 9 million of them were wounded or never returned home. 57,470 British soldiers—nearly the total number of American servicemen killed in the entire Vietnam War—were killed or wounded on the first day of fighting at the Battle of the Somme;[1]Charles F. Horne & Walter F. Austin, Great Events of the Great War (1923). This book is located in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. five months later, when the fighting there was done, one million men had been sacrificed in the name of advancing six miles into German-occupied territory. The totality of “the Great War” effectuated a generational trauma on a scale and severity the likes of which is hard for our modern minds to grasp.

The Armistice between Germany and the Allies was signed in the early morning hours of November 11, 1918, and by agreement the fighting stopped at 11:00AM on the same day. Although it would take nearly another year for the Treaty of Versailles,[2]William M. Malloy, Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocols and Agreements 1910-1923 (1919-1923). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. the official peace treaty that ended the state of war between Germany and the Allies, to be signed, the armistice signing, that euphoric moment when hostilities finally ceased, is today widely commemorated throughout the western world as Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, and Veterans Day. In 2018, the Imperial War Museum in London released a reconstruction of what that moment when the guns finally fell silent would have sounded like to the men on the front, using original sound ranging taken of artillery firing in the minute immediately preceding and following the armistice signing.

With the war over, millions of people struggled to make sense of the senseless. Because of the logistical challenges involved in repatriating so many dead, countless families were not able to recover the bodies of their loved ones. Britain and France had an official policy to not repatriate their fallen soldiers. British Army Chaplain David Railton, who had served on the Western Front, proposed a unique, cathartic idea to the dean of Westminster, that an unidentified British soldier buried on the battlefields of France be reinterred in Westminster Abbey—the burial site of Britain’s most prominent—to represent those war dead who had no known grave.

In Honored Glory

The Unknown Warrior was chosen from four anonymous servicemen exhumed from various battlefields in France, and arrived in London on November 11, 1920 to coincide both with Armistice Day and the unveiling of the Cenotaph[3]John W. Owens, Armistice Day in London, 88 ADVOC. PEACE 51 (1926). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in Whitehall. Hundreds of thousands turned out for the solemn occasion, “formed in triple lines”[4]John W. Owens, Armistice Day in London, 88 ADVOC. PEACE 51 (1926). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to pass by in “a ceaseless procession of pain.”[5]John W. Owens, Armistice Day in London, 88 ADVOC. PEACE 51 (1926). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. King George V and other ministers of state walked in the Unknown Warrior’s funeral procession to the Abbey, where an honor guard of 100 recipients of the Victoria Cross—the highest military honor in Britain—stood by as innumerable mourners filed past the casket. The ceremonies over, the Unknown Warrior’s grave was filled with soil brought from the major battlefields in France, and a temporary slab was installed reading “A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country. Greater love hath no man than this.” The following year, the United States awarded the Medal of Honor to the Unknown Warrior, delivered by General John J. Pershing,[6]John J. Pershing, My Experiences in the World War (1919). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Military and Government database. the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces on the Western Front; today it hangs on a pillar close to the tomb. A month after the Medal of Honor was awarded, the present black marble stone was installed. The final line of its inscription reads:

THEY BURIED HIM AMONG THE KINGS BECAUSE HE HAD DONE GOOD TOWARD GOD AND TOWARD HIS HOUSE

Across the Channel, coinciding with the ceremonies in Britain, France also buried its own unknown soldier on November 11, 1920. France’s Unknown Soldier is buried beneath the Arc de Triomphe at the center of Paris. An eternal flame keeps watch over his marble slab, which bears the inscription “Ici repose un soldat français mort pour la patrie 1914-1918” (“Here lies a French soldier who died for the fatherland 1914-1918”). As had also been done for the British Unknown, Congress bestowed the Medal of Honor[7]41 Stat. 1367 (1921). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. onto the French Unknown, and the Medal was again delivered[8]Robert C. Hall, Facing the Issue Squarely: A Plea for Supremacy of Law over Violence (1930). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. by General Pershing. Before this, mass burials of unidentified soldiers, such as the Civil War Unknowns[9]H.P. Caemmerer, Washington: The National Capital (1932). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. memorial at Arlington National Cemetery, were not uncommon, but the British and French Unknowns were something new; together, they are the first burial of a single unknown serviceman in a public setting.

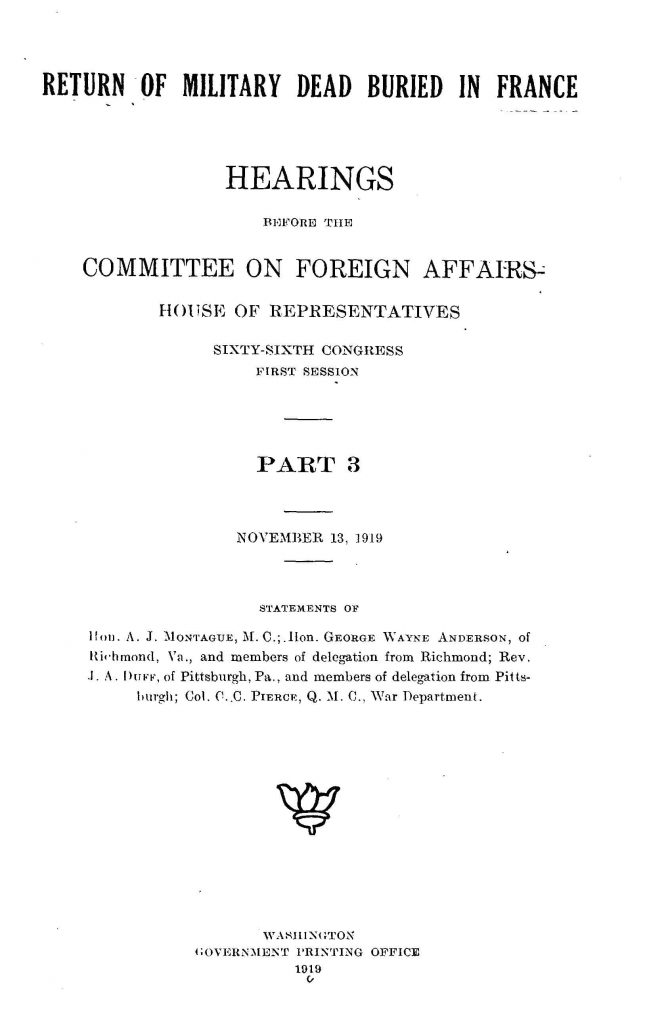

The United States officially entered World War I in 1917, with some 4 million American men eventually mobilizing for the war effort. Unlike France and Great Britain, the United States made a concerted effort to exhume and repatriate the bodies of fallen American soldiers.[10]Return of Military Dead Buried in France: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, First Session (1919). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. In 1919, the War Department estimated there were some 75,000 American soldiers buried in France across 829 cemeteries.[11]Authorizing the Appointment of a Commission to Remove the Bodies of Deceased Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, from Foreign Countries to the United States, and Defining Its Duties and Powers. Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of … Continue reading American soldiers had been issued aluminum identification discs, the precursors to modern “dog tags,”[12]Jan P. P. Ganschow, Identification of the Fallen: The Supply of Dog Tags to Soldiers as a Commandment of the Laws of War, 9 N.Z. ARMED F. L. REV. 21 (2009). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in hopes of identifying each fallen man and with a promise that his remains would be returned home unless objected to by the next of kin.[13]Return of Military Dead Buried in France: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, First Session (1919). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. But the practical reality was that identification and repatriation was not always possible.

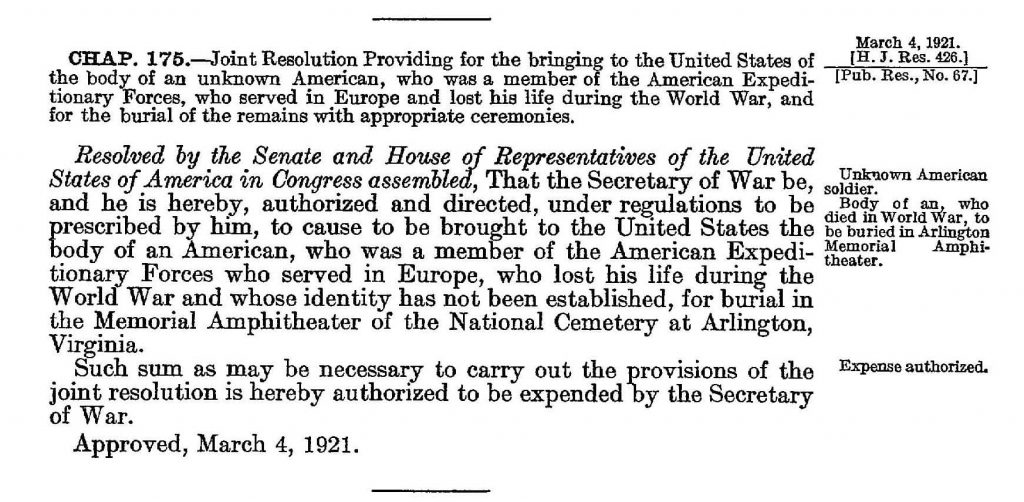

On December 21, 1920, Rep. Hamilton Fish III[14]J. T., Editor Salter, Public Men in and out of Office (1946). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. from New York introduced H.J. Res. 426,[15]60 Cong. Rec. 596 (1920). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. a joint resolution “providing for the bringing to the United States of the body of an unknown American killed on the battlefields of France, and for the burial of his remains with appropriate ceremonies.” A veteran of the war, Fish was no doubt inspired by the Unknown memorials in France and Britain. His bill was quickly reported on[16]H.R. Rep. 1292, 66th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1921). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. with an important change: that the unknown soldier be buried in the Memorial Amphitheater of Arlington National Cemetery. The bill passed[17]41 Stat. 1447 (1921). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. on March 4, 1921.

An Imperishable Soul Comes Home

Five months later, four unidentified American servicemen were exhumed from their wartime graves in France. They could have been soldiers, marines, or one of the first intrepid airmen; enlisted privates or non-commissioned officers; served in the infantry, artillery, or cavalry. Their unmarked, identical caskets were brought to the city hall at Châlons-sur-Marne[18]134 Cong. Rec. E1588 (1988). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. (now called Châlons-en-Champagne), a city approximately 166 miles west of Paris. On October 24, 1921, twenty-three-year-old Army Sergeant Edward Younger entered the room where the caskets lay, carrying a spray of white roses. A French military band was stationed outside, softly playing Chopin’s “Funeral March” as Sergeant Younger circled the four caskets three times. After his final circuit, he placed the white roses on the third casket from the left and saluted his unnamed fallen comrade. The unknown soldier to be interred at Arlington had been selected.

The Unknown then traveled by train to Le Havre, where he was placed aboard the USS Olympia,[19]H. Rep. 694, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. (1935). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. the flagship of Commodore George Dewey[20]Joseph L. Stickney. Admiral Dewey at Manila and the Complete Story of the Philippines: Life and Glorious Deeds of Admiral George Dewey, Including a Thrilling Account of Our Conflicts with the Spaniards and Filipinos in the Orient (1899). This book … Continue reading at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War. After arriving in Washington, D.C., the Unknown Soldier lay in state[21]H. G. Wells, Washington and the Riddle of Peace (1922). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. in the Capitol Rotunda. Almost 100,000 mourners passed by to pay their respects, including British author H.G. Wells.[22]H. G. Wells, Washington and the Riddle of Peace (1922). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. Despite so many assembled Americans, Wells contrasted the crowd with the ceaseless outpouring who turned out for the Unknown Warrior in London, a difference he partially attributed to the “remote distances of America.”[23]H. G. Wells, Washington and the Riddle of Peace (1922). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database.

On November 11, 1921, the Unknown Soldier was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.[24]Barbara Salazar Torreon, Defense Primer: Arlington National Cemetery (2021). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. Two minutes of silence was held nation-wide to mark the solemn moment. President Harding placed the Medal of Honor on the Unknown’s casket, and addressed the assembled crowd, saying, in part, “The name of him whose body lies here took flight with his imperishable soul … we know not whence he came, but only that his death marks him within everlasting glory of an American who died for his country.”[25]John A. Livingstone, Arlington, Mount Vernon and the White House—An Historic Pilgrimage, 37 COM. L.J. 535 (1932). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Foreign dignitaries who were present also conferred honors upon the Unknown Solider, including the Victoria Cross, reciprocating the honors bestowed by the United States onto other countries’ Unknowns. The ceremonies concluded, the Unknown Soldier’s grave was filled with soil from France,[26]134 Cong. Rec. E1588 (1988). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. as had been done for Britain’s Unknown Warrior.

A plain marble slab originally covered the Unknown Soldier’s grave, with the intention of adding a large tomb at a later date. The present tomb we see today was authorized by Congress on July 3, 1926[27]44 Stat. 914 (1926). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. and took nearly six years to complete, finally finishing on April 9, 1932. President Herbert Hoover officially dedicated[28]1932 Pub. Papers 808 (1932). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. the Tomb that same year on Armistice Day, November 11.

World War I may have been “the Great War,” but it was far from the last war; twenty years after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, World War II began. Congress considered adding another Unknown Soldier[29]H. Rep. 1799, 79th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1946). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. to the Tomb to represent the American lives lost in this new global conflict, and while the idea quickly passed,[30]60 Stat. 302 (1946). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. its execution was delayed. Ten years later, Congress again debated[31]H. Rep. 2503, 84th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1956). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. expanding the Tomb to include an Unknown from the Korean War.[32]70 Stat. 1027 (1956) This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. Both plans were finally put into action in 1958, with the Unknowns from World War II and Korea buried together with full honors in a joint ceremony on May 30, 1958.

Unknown No More

The conclusion of the Vietnam War naturally led to discussions of once again interring another anonymous American soldier at the Tomb. But revisions in military identification procedure had fundamentally changed the world into one of more certainty and closure than had existed in 1918. While President Nixon declared that all U.S. servicemen taken prisoner during the war had been accounted for after Operation Homecoming[33]Americans Missing in Southeast Asia: Hearings before the House Select Committee on Missing Persons in Southeast Asia, Ninety-fourth Congress, First Session (1975). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents … Continue reading in 1973, some 2,600 men were still either missing in action or killed in action and never recovered. That same year, the Department of Defense established the Central Identification Laboratory—Thailand[34]POW/MIA Affairs: Issues Related to the Identification of Human Remains from the Vietnam Conflict (1992). This report can be found in HeinOnline’s GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions database. to continue the work of recovering all American servicemen still in southeast Asia.

The possibility of adding an unknown American soldier killed in Vietnam was met with unease: the government could, and should, do its utmost to identify all “unknown” soldiers from the Vietnam War.

Despite these concerns, a Vietnam Unknown was selected and interred beside his Unknown comrades on May 28, 1984. But the efforts to identify him never ceased, thanks largely to the work of POW/MIA activists, who, using old-fashioned investigation techniques, narrowed in on a probable identity for the man buried in the Vietnam crypt. The advent and rise of DNA testing led to the Vietnam Unknown being positively identified[35]Eric A. Fischer, DNA Identification: Applications and Issues (2001). This report can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. in 1998 as Air Force 1st Lt. Michael Joseph Blassie, who had been killed in 1972 when his plane was shot down near An Lộc. Having been identified, Blassie was exhumed and reinterred by his family at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery. Rather than inter another unidentified Vietnam soldier, the inscribed slab previously covering the Vietnam Unknown’s crypt was replaced with one that reads “Honoring and keeping faith with America’s missing servicemen.” The crypt remains vacant, in hopes that there will be never be another “unknown”[36]Improving Recovery and Full Accounting of POW/MIA Personnel from All Past Conflicts: Hearing before the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session … Continue reading soldier to rest beneath the Tomb.

Home to History

We love history here at the HeinOnline Blog, and we bring it to life with millions of documents that show what the people who lived these moments thought and felt about the times they lived in. Bring your inbox to life by subscribing to the HeinOnline Blog and receiving more posts like this one directly to your email.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Charles F. Horne & Walter F. Austin, Great Events of the Great War (1923). This book is located in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | William M. Malloy, Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocols and Agreements 1910-1923 (1919-1923). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library. |

| ↑3, ↑4, ↑5 | John W. Owens, Armistice Day in London, 88 ADVOC. PEACE 51 (1926). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | John J. Pershing, My Experiences in the World War (1919). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Military and Government database. |

| ↑7 | 41 Stat. 1367 (1921). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑8 | Robert C. Hall, Facing the Issue Squarely: A Plea for Supremacy of Law over Violence (1930). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. |

| ↑9 | H.P. Caemmerer, Washington: The National Capital (1932). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑10, ↑13 | Return of Military Dead Buried in France: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, First Session (1919). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑11 | Authorizing the Appointment of a Commission to Remove the Bodies of Deceased Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, from Foreign Countries to the United States, and Defining Its Duties and Powers. Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, First Session, on H. R. 9227 (1919). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑12 | Jan P. P. Ganschow, Identification of the Fallen: The Supply of Dog Tags to Soldiers as a Commandment of the Laws of War, 9 N.Z. ARMED F. L. REV. 21 (2009). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14 | J. T., Editor Salter, Public Men in and out of Office (1946). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑15 | 60 Cong. Rec. 596 (1920). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑16 | H.R. Rep. 1292, 66th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1921). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑17 | 41 Stat. 1447 (1921). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑18, ↑26 | 134 Cong. Rec. E1588 (1988). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑19 | H. Rep. 694, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. (1935). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑20 | Joseph L. Stickney. Admiral Dewey at Manila and the Complete Story of the Philippines: Life and Glorious Deeds of Admiral George Dewey, Including a Thrilling Account of Our Conflicts with the Spaniards and Filipinos in the Orient (1899). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑21, ↑22, ↑23 | H. G. Wells, Washington and the Riddle of Peace (1922). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s History of International Law database. |

| ↑24 | Barbara Salazar Torreon, Defense Primer: Arlington National Cemetery (2021). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑25 | John A. Livingstone, Arlington, Mount Vernon and the White House—An Historic Pilgrimage, 37 COM. L.J. 535 (1932). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑27 | 44 Stat. 914 (1926). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑28 | 1932 Pub. Papers 808 (1932). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑29 | H. Rep. 1799, 79th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1946). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑30 | 60 Stat. 302 (1946). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑31 | H. Rep. 2503, 84th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1956). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑32 | 70 Stat. 1027 (1956) This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑33 | Americans Missing in Southeast Asia: Hearings before the House Select Committee on Missing Persons in Southeast Asia, Ninety-fourth Congress, First Session (1975). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑34 | POW/MIA Affairs: Issues Related to the Identification of Human Remains from the Vietnam Conflict (1992). This report can be found in HeinOnline’s GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions database. |

| ↑35 | Eric A. Fischer, DNA Identification: Applications and Issues (2001). This report can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑36 | Improving Recovery and Full Accounting of POW/MIA Personnel from All Past Conflicts: Hearing before the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session (2009). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |