With former president Donald Trump currently under investigation for keeping classified documents from his presidency in his Mar-a-Lago home, you might wonder if a major American politician has ever been suspected of conspiring against the United States before. Well, it isn’t exactly unprecedented: Aaron Burr, vice president to Thomas Jefferson and infamously known as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel, was charged with treason in 1807. Though found not guilty, Burr’s actions and the subsequent trial ruined his political career and reputation. Let’s dive into the drama in this month’s Secrets of the Serial Set edition.

Desperate for Power

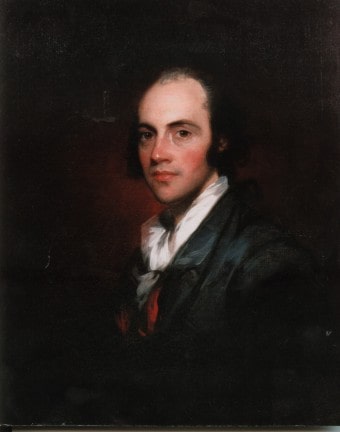

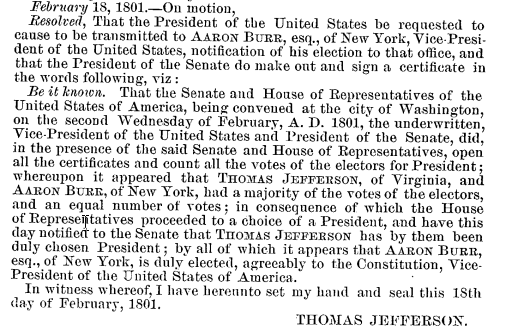

Aaron Burr had once been a respected name in the United States. After all, he was a hero of the Revolutionary War, during which he served with distinction as a Continental Officer. He went on to become a United States Senator and New York State Attorney General and Assemblyman. His last major position was as Thomas Jefferson’s vice president[1]“Examining and counting electoral votes for President and Vice-President of United States.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1872, pp. 1-36. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20441&i=343. … Continue reading—at the time, presidents and vice presidents didn’t run together, but rather the vice presidency was filled by the person who came in second during the presidential election. Therefore, Jefferson was not a big fan of Burr, especially after Burr fatally shot Alexander Hamilton in a duel.[2]“Alexander Hamilton Bicentennial final report.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1958, pp. I-84. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22594&i=684. This document can be found in … Continue reading Left without hopes of ever gaining the presidency, Burr began desperately searching for an opportunity to rebuild his political fame and fortune.

The Wild West of Opportunity

During the early 1800s, the Louisiana Purchase territory was still mainly unsettled, and the settlers who had moved out there supported secession from the United States, so Burr decided to capitalize on this opportunity, allegedly to create his own country with himself in charge. It is still debated amongst historians how much land he wanted to take—whether it was just parts of Texas and Louisiana, or if he wanted to take parts of Mexico as well. However, regardless of his ultimate goal, Burr, still serving his term as vice president, met with Anthony Merry, British Minister to the U.S.,[3]“Instructions to the British Ministers to the United States – Volume III of the American Historical Association Report, 1936.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1937, p. I-403. HeinOnline, … Continue reading several times throughout 1804 and 1805. In exchange for money and weapons, Burr would “lend his assistance to His Majesty’s Government in any manner in which they may think fit to employ him, particularly in endeavoring to effect a separation of the Western part of the United States from that which lies between the Atlantic and the mountains.” Merry let the British government know of Burr’s intentions, but the Crown never sent any support or assistance to him, and Merry was eventually recalled to Britain.

Burr proceeded to travel along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers in search of people willing to back him on his scheme. His key supporter-turned-snitch was James Wilkinson, the commanding general of the United States Army who was notoriously known for his previous attempt to secede Kentucky and Tennessee from the Union[4]“Brigadier General James Wilkinson: inquiry into his conduct and dealings with Spain, Aaron Burr, and others (11-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 38, 1809, pp. 79-127. HeinOnline, … Continue reading (he also ended up being a paid agent for Spain[5]“Brigadier General James Wilkinson: inquiry into his conduct and dealings with Spain, Aaron Burr, and others (11-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 38, 1809, pp. 79-127. HeinOnline, … Continue reading). Wilkinson’s access to troops and weapons made him an important partner for Burr—at first. Burr managed to persuade President Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson governor of the Louisiana Purchase, which would give Wilkinson access to the territory without garnering any suspicion.

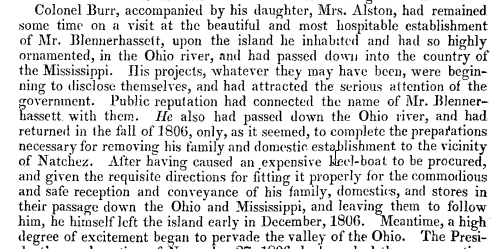

Another important supporter in Burr’s mission was Harman Blennerhassett,[6]“Memorial of heirs of Harman Blennerhassett, conspirator with Aaron Burr, for indemnity for destroyed property.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1851, pp. 1-16. HeinOnline, … Continue reading a wealthy Irish immigrant who possessed an entire island on the Ohio River, where he had built a mansion. Burr and his supporters began using the island to stock men and supplies. However, the governor of Ohio became suspicious of what was going on over on Blennerhassett Island, and he ordered the state militia to raid the island, resulting in the destruction of Blennerhasset’s home,[7]“Memorial of heirs of Harman Blennerhassett, conspirator with Aaron Burr, for indemnity for destroyed property.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1851, pp. 1-16. HeinOnline, … Continue reading although he managed to escape and met Burr on the Cumberland River,[8]“Natchez Trace Parkway survey.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1940, p. I-[i]. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset23273&i=52. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading where he and his posse were heading toward New Orleans to meet up with the troops that Wilkinson had promised to send.

Burr’s Capture and Trial

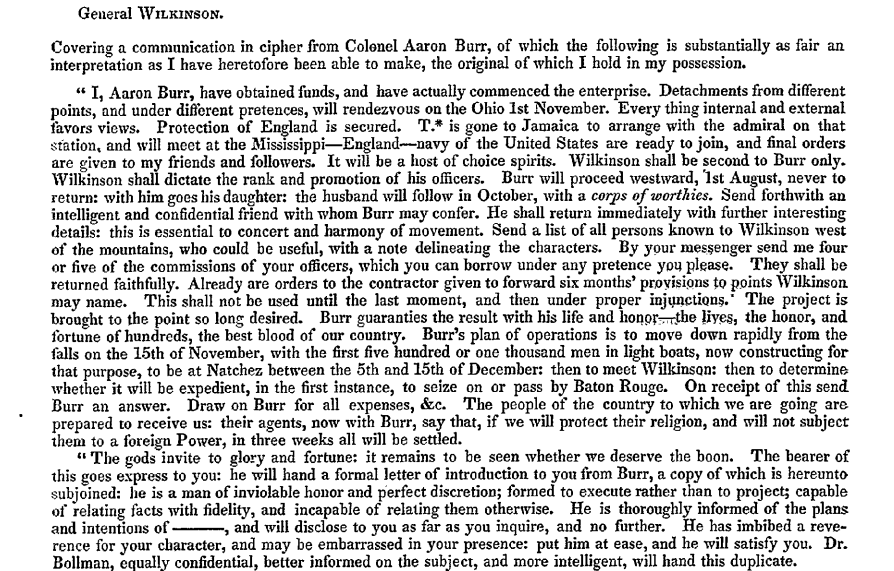

By early 1806, Joseph Hamilton Daveiss, the federal attorney for Kentucky, had become suspicious of Burr’s actions and wrote multiple times to President Jefferson to warn him that Burr was planning a rebellion in the Southwest.[9]“Calendar of correspondence of Thomas Jefferson in State Department, pt. 2: Letters to Jefferson.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1901, p. I-576. HeinOnline, … Continue reading However, Jefferson ignored the letters, believing them to be politically motivated. But by the middle of 1806, Jefferson noticed that something was stirring in the Louisiana Purchase territory, and his suspicions were confirmed by none other than Wilkinson himself. Burr had sent a coded letter to Wilkinson—now known as the Cypher Letter—outlining his intentions.[10]“Burr’s conspiracy, no. 2; arrests of Samuel Swartwout, Peter V. Ogden and James Alexander (9-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1806, pp. 471-473. HeinOnline, … Continue reading Wilkinson, suspecting that Burr’s plan was bound to fail, decided to turn the letter in to Jefferson, but not before making significant edits to the letter to avoid any incrimination of himself.

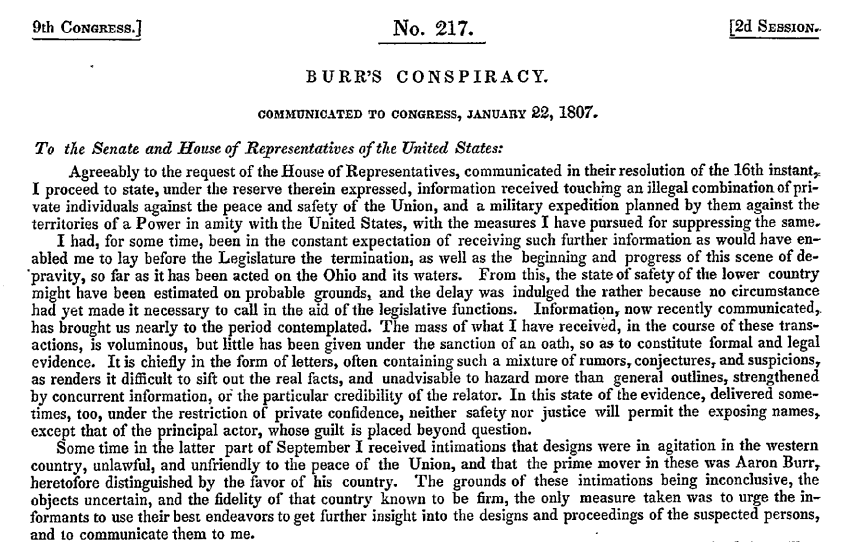

Jefferson subsequently warned Congress of Burr’s plan and ordered the arrest of any of his conspirators,[11]“Burr’s conspiracy, no. 1; Presidential message with letters from General James Wilkinson and Erick Bollman (9-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1806, pp. 468-471. HeinOnline, … Continue reading while also alerting authorities in the West to be on the lookout. Jefferson also ordered Burr’s arrest, and Burr was taken into custody in New Orleans. He managed to temporarily escape into the wilderness, but he was found on February 1, 1807, and was sent back to Virginia for trial.

On trial, Burr was charged with treason.[12]“Burr’s conspiracy, no. 6; trial at Richmond, Virginia, pt. 1: Proceedings (10-1).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1807, pp. 486-645. HeinOnline, … Continue reading Jefferson, desperate to get Burr convicted, offered a pardon to any witnesses who agreed to testify against him. However, the case called into question the very specific definition of “treason” in the Article III, Section III of the Constitution, where it is defined specifically as “levying War” against the United States.[13]Text of the Constitution up to Amendment [XXVII], with analytical index 9 (1789)

Article V [Concerning Amendments]. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. Were Burr’s intentions enough to qualify as treason, even if he hadn’t actually succeeded in taking any action to bring about a mutiny and secession of the Southwest territories? The judge presiding, Chief Justice John Marshall, much to Jefferson’s fury, decided that mere intention wasn’t enough to convict Burr of treason,[14]“Burr’s conspiracy, no. 6; trial at Richmond, Virginia, pt. 1: Proceedings (10-1).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1807, pp. 486-645. HeinOnline, … Continue reading and he was acquitted.

The Aftermath

Although Burr went free, the rest of his life would be marred by his conspiracy. After his trial, effigies of Burr were hanged across the country. As a result, in order to protect himself, he went on a self-imposed exile to Europe,[15]“Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789-1993.” Congressional Serial Set, , 1996, pp. 1-619. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset51421&i=67. This document can be found in … Continue reading where he proceeded to request support from England and France for a revolution in Mexico, but he was denied. With his tail between his legs, he returned to the United States in 1811, where he changed his name and resumed his law practice in New York. Deeply in debt, Burr died on September 14, 1836.

After Burr’s vice presidency, the 12th Amendment was passed, which would require presidents and vice presidents to be elected by separate electoral votes.[16]“Constitutional amendment concerning term of office of President, Vice-President, Senators and Representatives.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1909, pp. 1-6. HeinOnline, … Continue reading

Today, historians disagree on many details of Burr’s conspiracy. What was his true goal? How many supporters did he actually have? These are questions that may remain unanswered.

Help Us Complete the Project

Secrets of the Serial Set is an exciting and informative blog series from HeinOnline dedicated to unveiling the wealth of American history found in the United States Congressional Serial Set. Documents from additional HeinOnline databases have been incorporated to supplement research materials for non-U.S. related events discussed.

If your library holds all or part of the Serial Set, and you are willing to assist us, please contact Steve Roses at 716-882-2600 or sroses@wshein.com. HeinOnline would like to give special thanks to all of the libraries that have provided generous contributions which have resulted in the steady growth of HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | “Examining and counting electoral votes for President and Vice-President of United States.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1872, pp. 1-36. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20441&i=343. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Alexander Hamilton Bicentennial final report.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1958, pp. I-84. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset22594&i=684. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑3 | “Instructions to the British Ministers to the United States – Volume III of the American Historical Association Report, 1936.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1937, p. I-403. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset36449&i=18. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑4 | “Brigadier General James Wilkinson: inquiry into his conduct and dealings with Spain, Aaron Burr, and others (11-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 38, 1809, pp. 79-127. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0002&i=101. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑5 | “Brigadier General James Wilkinson: inquiry into his conduct and dealings with Spain, Aaron Burr, and others (11-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 38, 1809, pp. 79-127. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0002&i=91. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑6, ↑7 | “Memorial of heirs of Harman Blennerhassett, conspirator with Aaron Burr, for indemnity for destroyed property.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1851, pp. 1-16. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset37451&i=496. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑8 | “Natchez Trace Parkway survey.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1940, p. I-[i]. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset23273&i=52. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑9 | “Calendar of correspondence of Thomas Jefferson in State Department, pt. 2: Letters to Jefferson.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1901, p. I-576. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset30050&i=146. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑10 | “Burr’s conspiracy, no. 2; arrests of Samuel Swartwout, Peter V. Ogden and James Alexander (9-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1806, pp. 471-473. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0001&i=477. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑11 | “Burr’s conspiracy, no. 1; Presidential message with letters from General James Wilkinson and Erick Bollman (9-2).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1806, pp. 468-471. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0001&i=474. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑12 | “Burr’s conspiracy, no. 6; trial at Richmond, Virginia, pt. 1: Proceedings (10-1).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1807, pp. 486-645. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0001&i=648. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑13 | Text of the Constitution up to Amendment [XXVII], with analytical index 9 (1789) Article V [Concerning Amendments]. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑14 | “Burr’s conspiracy, no. 6; trial at Richmond, Virginia, pt. 1: Proceedings (10-1).” American State Papers: Miscellaneous, 37, 1807, pp. 486-645. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.congrec/aspmsc0001&i=647. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑15 | “Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789-1993.” Congressional Serial Set, , 1996, pp. 1-619. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset51421&i=67. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑16 | “Constitutional amendment concerning term of office of President, Vice-President, Senators and Representatives.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1909, pp. 1-6. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset25537&i=186. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |