This past weekend our nation experienced a great, patriotic, unifying celebratory occasion. Step aside, Independence Day. On July 3rd, Hamilton was finally released on Disney+. Filmed across three performances in June 2016, the film version captures the stage production of the hit musical with its original cast and brings it into the comfortable and affordable living rooms of the masses. Now that we’ve all had a few days to rewatch it a couple or dozen times, let’s unpack this American musical with some supplementary materials from your favorite research database.

Don’t say no to this! Make sure you are subscribed to the databases we’ll be referencing so you can follow along:

- Legal Classics

- Taxation & Economic Reform in America Parts I & II

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

- World Constitutions Illustrated: Contemporary & Historical Documents and Resources

- World Trials

Farmer Refuted

Hamilton’s first political writings were two anonymous pamphlets, A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress (1774) and The Farmer Refuted (1775). As dramatized in the musical, Hamilton was responding to Bishop Samuel Seabury’s own series of pamphlets in which he promoted the Loyalist cause, which rejected revolution in favor of remaining part of the British Empire. Seabury wrote under the pen name “A. W. Farmer,” an abbreviation for ‘a Westchester farmer,’ hence the title of both the real-life pamphlet and the song. While not an in-the-streets confrontation, Hamilton does tear the dude apart with this savage 18th century takedown:

… [Seabury’s pamphlet] has been the source of abundant merriment to me. The spirit that breathes throughout, is so rancorous, illiberal, and imperious; the argumentative part of it is so puerile and fallacious; the misrepresentations of facts, so palpable and flagrant; the criticisms so illiterate, trifling, and absurd; the conceits so low, sterile, and splenetic; that I will venture to pronounce it one of the most ludicrous performances which has been exhibited to public view during all the present controversy. You have not even imposed on me the laborious task of pursuing you through a labyrinth of subtilty. You have not had ability sufficient, however violent your efforts, to try the depths of sophistry; but have barely skimmed along its surface.”

Ten Duel Commandments

Dueling is a custom of honor that spans cultures and centuries. Dating back to medieval times, by the 1600s duels were no longer contests fought by knights but were rather a privilege of the well-bred gentleman. In Hamilton’s time, Enlightenment thinkers in Europe began to attack dueling as a barbaric leftover of the past.

But across the sea in America, dueling was incredibly popular, especially in the chivalrous culture of the South and among military officers (“This is commonplace, especially among recruits / Most disputes die and no one shoots.”) Between 1798 and 1861, the United States Navy lost two-thirds as many officers to dueling as it did to combat.

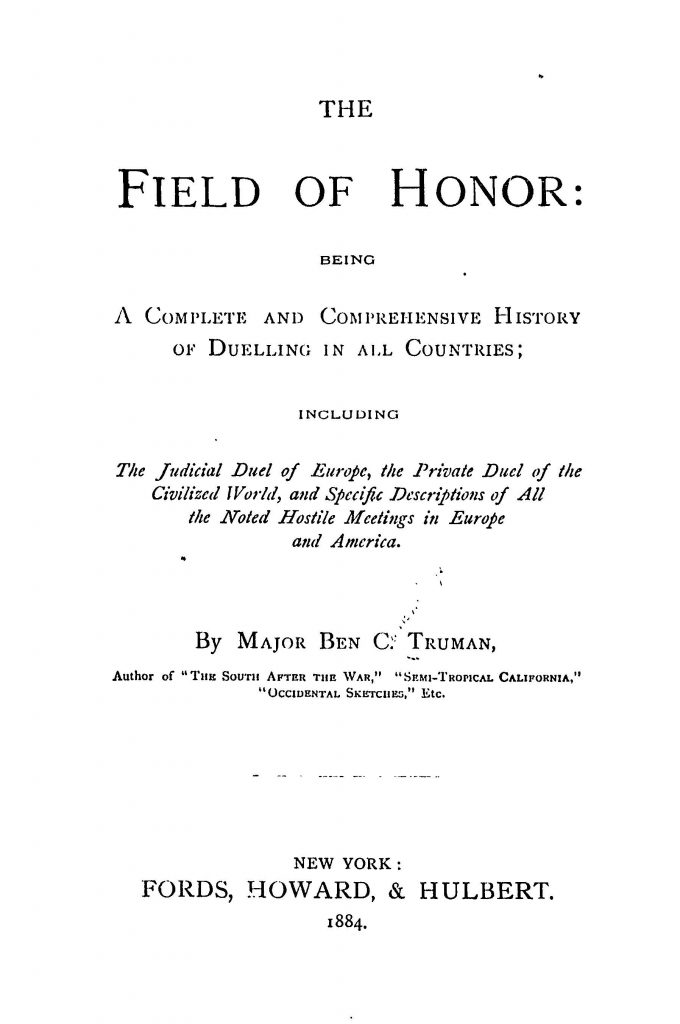

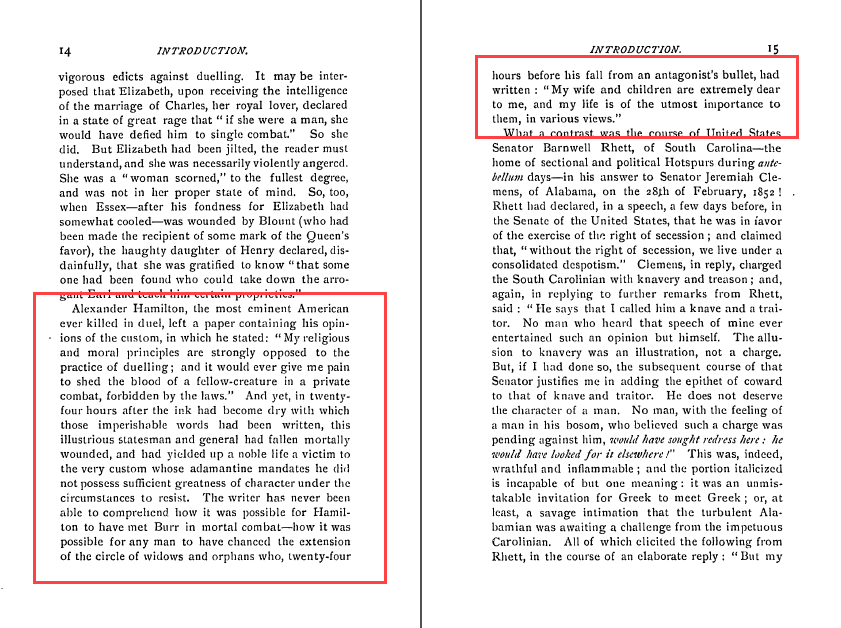

Hamilton was involved in or connected to three duels in his life: the duel between General Charles Lee and Colonel John Laurens, where he served as Laurens’ second; the duel in which his eldest son, Philip, was killed; and the duel with Aaron Burr that ended his own life. Hamilton wrote his own account of Laurens’ duel, but accounts of all three can be found in this interesting gem in our World Trials collection:

You may be surprised to learn from its account of Philip Hamilton’s duel a detail that did not make its way into the musical: there were two duels. Philip and his friend Stephen Price confronted George Eacker, who had insulted Alexander Hamilton in a Fourth of July speech. Eacker insulted both young men, and Price challenged Eacker to a duel. Price’s duel ended with four shots fired but no one injured, a result that the young Hamilton apparently found “so unsatisfactory” that he then challenged Eacker to a duel the next day, which was to prove a fatal appointment for Philip.

It’s worth paging back to the beginning of this particular work for its brief early commentary on Hamilton’s duel, including the author’s own condemnation of the ten-dollar founding father:

Man, the Man Is Nonstop!

Hamilton and Burr served as co-counsel in the trial of Levi Weeks, the first murder trial in America for which there is a formal record. While the musical plays around with timelines to serve its narrative arc and to fit in the phenomenal amount of historical knowledge it contains, Weeks’ trial actually occurred in 1800, long after Hamilton was appointed to the Constitutional Convention and relatively late in his career. Hamilton and Burr were not Weeks’ only lawyers; they represented him along with Henry Brockholst Livingston, who would eventually become an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Weeks’ trial was a cause célèbre in its day. In 1799, Levi Weeks was twenty-three years old and working as a carpenter for his brother Ezra, one of the most famous builders in New York at the time. Levi took lodgings at a boarding house on Greenwich Street, where he met fellow-lodger Gulielma “Elma” Sands. The two began a secret relationship until Elma mysteriously disappeared on December 22, 1799 after leaving the boarding house with Levi. Two days later Elma’s muff was discovered near the newly dug Manhattan Well; on January 2, her strangled body was recovered from the well.

The affair became known as the Manhattan Well Murder. Levi was able to retain such illustrious legal representation through his brother’s wealth and connections. Damning testimony was given against Weeks at trial, including a witness who saw Weeks taking measurements of the well prior to the murder. But Weeks was acquitted after five minutes of deliberation by the jury. Convicted in the court of public opinion, Weeks left New York and relocated to Mississippi, where he became a well-respected architect. Today, the well survives inside a COS clothing store in SoHo and is rumored to be haunted.

The Reynolds Pamphlet (have you read this??)

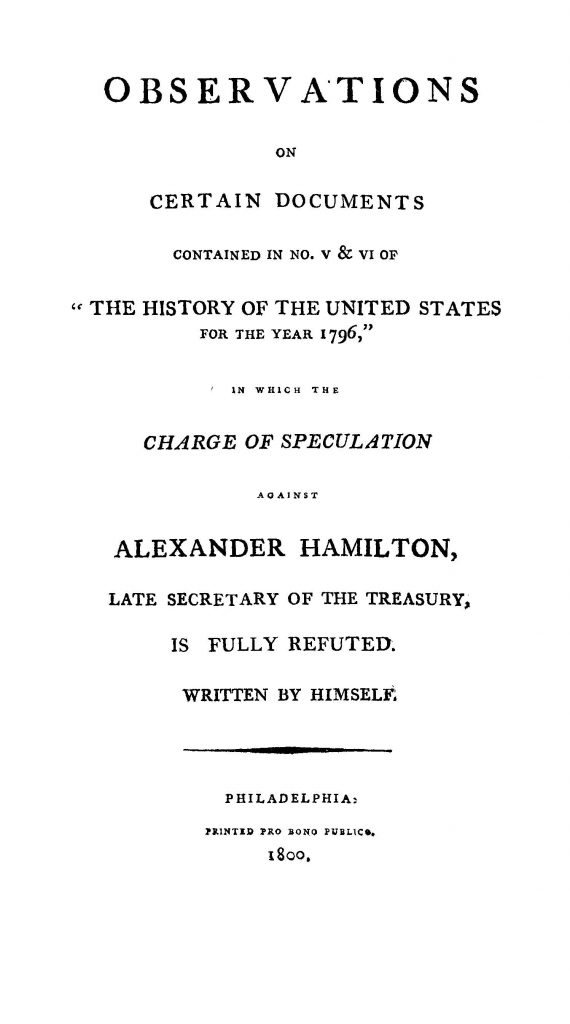

The start of the Hamilton-Reynolds affair, one of the first sex scandals in American politics, is detailed in the musical, although the real-life events took place over a much longer period of time than one might glean from the show. Public knowledge of the affair first came to light in 1792, when James Reynolds began blabbing about Hamilton’s affair with his wife, Maria, as a bargaining chip to get out of some legal trouble. Unlike as shown in the musical, James Monroe, Senator Abraham Venable, and Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg confronted Hamilton about the rumors, to which Hamilton confessed, turning over letters from the Reynoldses as proof. Monroe then sent the letters to Thomas Jefferson, who began circulating the rumors again five years later. At the same time, the letters had been leaked to journalist James Thomson Callender, who began publishing them in a series of pamphlets. Hamilton called out Monroe, to whom he had given the letters, and the two nearly dueled over the argument, which was only avoided after the intercession of Aaron Burr. The Reynolds Pamphlet, the colloquial name given to it, was published by Hamilton in 1797, in which he owned up to the affair but denied any corruption or abuse of his official office.

Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story

Eliza Hamilton, Alexander’s wife, lived a life deserving of her own musical. Born in 1757 into one of New York’s richest and most influential families, the Van Rensselaers, Eliza was the second of fourteen children. Her father, Philip Schuyler, was a general in the Continental Army and later a United States Senator representing New York. She met Alexander in 1780 and shortly afterwards the two were married; they would have eight children together and would also take in Fanny Antill, the orphaned daughter of Alexander’s friend Edward Antill. Eliza was an indispensable aid to her husband; she copied out his writings and letters, acted as a sounding board when Alexander was writing Washington’s Farewell Address, and was an intermediary between Alexander and his publisher for The Federalist Papers.

After Alexander’s death, Eliza reorganized her husband’s writings with the help of their son, John Church, and aided him as he was writing History of the Republic of the United States of America, as Traced in the Writings of Alexander Hamilton and His Contemporaries. John Church was a devoted biographer of his father. He worked with Congress to publish The Works of Alexander Hamilton; Comprising His Correspondence, and His Political and Official Writings, Exclusive of the Federalist, Civil and Military. He later commissioned a statue of his father, which was installed in Central Park and dedicated in 1880.

Eliza told not only her husband’s story. In her 90s, she joined forces with Dolley Madison and Louisa Adams to raise money to build the Washington Monument, whose construction took more than forty years. She was present at the laying of the Monument’s cornerstone in 1848.

Eliza lived another fifty years after the death of Alexander, dying in 1854 at the age of 97. The orphanage she helped found in 1806, the New York Orphan Asylum Society, still exists today as Graham Windham, the oldest non-profit in America.

Finally, one of Hamilton’s lasting achievements, his national bank, was created under the view that Congress had the power to do what is “necessary and proper” to enact provisions of the Constitution; in Hamilton’s view, Congress’s mandate to regulate interstate commerce and issue currency necessitated his bank as necessary and proper. Jefferson disagreed with Hamilton’s interpretation of the necessary and proper clause, but the dispute was settled in the 1819 Supreme Court decision McCulloch v Maryland, which upheld the legality of the national bank and ruled that the clause gave the federal government implied powers not explicitly stated in the Constitution.

Aaron Burr, Sir

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr’s fateful date in Weehawken was precipitated by Burr’s ill-fated run for governor of New York, not for Hamilton’s endorsement of Jefferson in the election of 1800, although the later certainly did nothing to improve relations between the two. After being dropped from Jefferson’s presidential ticket in the 1804 election, Burr hoped to return gloriously to New York politics but he instead was soundly and embarrassingly defeated by Morgan Lewis. Burr blamed the loss on a vicious smear campaign orchestrated notably by newspaper editor James Cheetham. The mudslinging escalated in April 1804, when the Albany Register published a letter from Alexander Hamilton in which he characterized Burr as “a dangerous man.”

The exchange of letters that followed between the two old friends only threw kindling on the fire, rather than stamping it out. On July 11, 1804, they took the field at Weehawken.

After the duel, Burr served out his role as Vice President. He was never formally charged for killing Hamilton, but Burr would soon find himself in another controversy. After leaving the vice-presidency, Burr went west, eventually leasing 40,000 acres of land from the Spanish government in present-day Louisiana and gathering together a small armed group of men. Skepticism swirled over the purpose of Burr’s armed expedition. His army could have been formed to overthrow Spanish holdings in Texas and Mexico and establish Burr the ruler of a new nation within the United States; after all, in 1804, Burr offered to work with England to force this secession within the United States.

Adding to the speculation, Burr had access to an island on the Ohio River, from which he planned to base his forces, and an alliance with General James Wilkinson, senior brigadier general of the army and governor of the Louisiana Territory. Wilkinson eventually turned on Burr, notifying President Jefferson what his former vice president was up to. In 1807, Burr was arrested for treason. He was found not guilty, but with his reputation ruined Burr exiled himself to Europe. He returned to the United States in 1813. Dogged by creditors and plagued by money troubles for the rest of his life, Burr died at the age of 80 in 1836.

Don’t Throw Away Your Shot!

Let us tell you more stories by subscribing to the blog so you’ll have posts just like this delivered straight to your inbox.