What is a child? It may seem like a silly question, but the answer is more nuanced than one might think. In biology, the term refers to the state of the human being between birth and puberty. Legally, itrefers to a person younger than a predetermined age of majority—the point in time when a person can take legal control over their actions and decisions. Symbolically, children have become much more. Over the past several hundred years, the child has become not only an allegory for innocence and the embodiment of freedom, but also a shining beacon of hope for future generations widely considered in need of adult protection.

Pre-20th Century Children

Though this view of the child is one we’re all familiar with now, it wasn’t always the case. In antiquity, children were seen as equal to adults, yet incomplete, and often spent the biological period of “childhood” learning the skills required of them later in life. The concept of childhood as a period of innocence and freedom did not truly exist until the 1600s, when philosophers such as John Locke deeply considered the concept of the “self” and its development. Locke, in particular, posited the tabula rasa in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding—the theory that the human mind is empty at birth and shaped by experience.

This understanding of the human being became particularly influential in the Western world with the rise of religious movements such as Puritanism and economic theories such as capitalism. A new family ideology was born, centered around the proper upbringing of children in a way that would guide them toward successful physical and spiritual lives. It was around this period that children were recognized to have inherent rights, namely the right to sustenance and proper education.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, artists and authors began to romanticize childhood in their fine art, poetry, and prose, associating young people with freedom, spontaneity, creativity, and emotion. However, despite this romantic notion of youth, many young people found themselves forced into labor, and even indentured servitude, for much of their adolescence. As the Western world industrialized, much of this labor meant working long hours in dangerous factory or mining jobs.

Toward the end of the 19th century, dissonance between the idealistic notion of childhood and the reality of child exploitation culminated in social movements for change. The first campaigns for legal protection for children appeared, leading to legislation such as the 1833 Ten Hours Act in Great Britain. The act placed a restriction on the age and working hours of children in certain industries.

At around the same time, the state of Massachusetts passed the first state child labor law, stating that children under 15 years of age working in factories were required to attend school for at least 3 months out of the year. Massachusetts continued to be the first in protecting the rights of children, limiting young people to 10 working hours a day in 1842, and then requiring fit adoptive parents in 1851. In the following decades, compulsory schooling was introduced state by state, transitioning children out of the workplace and into the classroom. Read an overview of the history of U.S. education in this blog post.

Children in the 20th and 21st Centuries

Much more consideration has been given to protecting the rights of children in both U.S. and international law since 1900. See the timeline below for an overview.

Early 20th Century

1909: Theodore Roosevelt held the first White House Conference on Children to discuss eliminating the institutionalization of dependent or neglected children. In response to the conference, the United States Children’s Bureau was formed by Congress, the first federal agency in the country (and world) dedicated solely to improving the lives of children.

1916: The first federal child labor law prevented the transfer of goods across state lines if minimum age laws were violated, but the law was declared unconstitutional in Hammer v. Dagenhart.

1919: The White House Conference on Standards of Child Welfare created the most comprehensive report on the needs of children ever written.

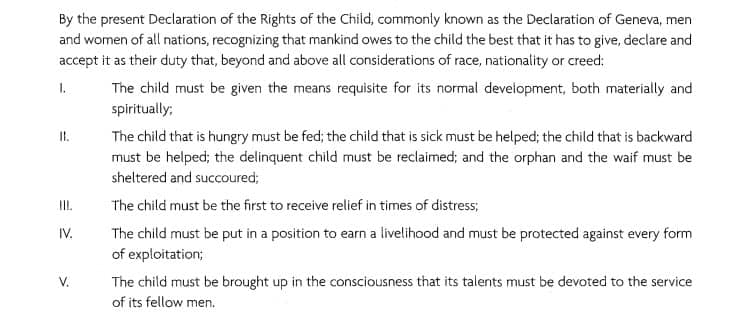

1924: The League of Nations adopted the historic Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child, the first human rights instrument approved by an international institution.

A precursor to the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child, the document was the first recognition of rights specific to children. The enumerated rights included: the right of a hungry child to be fed; the right to a name; the right to health care; and the right to education, among others.

In the same year, Congress attempted to pass a constitutional amendment authorizing a national child labor law, but the attempt was blocked and the bill was dropped.

1938: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, part of his New Deal, outlawing many forms of child labor. Read more about FDR’s New Deal programs in this blog post.

1944: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Prince v. Massachusetts that parental authority can be limited by the government in the interest of a child’s welfare.

1948: The UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Consisting of 30 articles that detail individual rights such as the right to life, prohibition of slavery, and freedom of thought (among others), the document has since been invoked in several international treaties, national constitutions, and regional human rights instruments. Importantly, the declaration also mentions that special care should be given to both mothers and children.

Mid-to-Late 20th Century:

1959: The United Nations adopted an extended form of the previous Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child.

That same year, the declaration was endorsed by the 1959 White House Conference on Children and Youth. Read President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s address to the conference.

1965: The U.S. Supreme Court welcomed Abe Fortas, a long-time advocate of children’s rights. While on the Court, Fortas focused heavily on U.S. juvenile justice, and wrote the majority decision in Kent v. United States, the first case evaluating juvenile court procedure.

1967: The landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision for In re Gault was delivered, stating that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause applies to juvenile defendants.

1969: Tinker v. Des Moines was another landmark decision from the Supreme Court, defining the First Amendment rights of students in public schools.

1974: The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act was passed by Congress, defining the terms “child abuse” and “neglect,” while also establishing the National Center on Child Abuse, the Office on Child Abuse and Neglect, and the National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect Information.

1978: Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, providing tribal governments the exclusive jurisdiction over children living on their reservations.

1980: President Bill Clinton signed into law the Adoption and Safe Families Act, the most sweeping change in the U.S. adoption care system in decades. Importantly, the act encouraged timely permanency planning to speed up foster children’s paths to permanent homes, either with relatives or adoptive parents, while promoting the importance of children’s safety and well-being during the process.

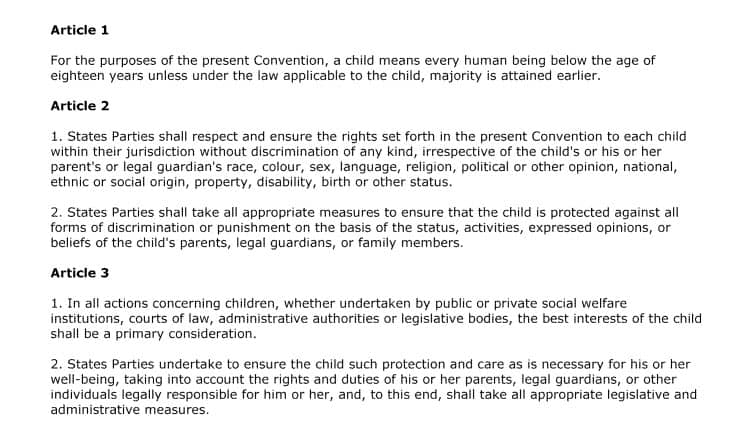

1989: The United Nations put forth the Convention on the Rights of the Child, a binding international legal instrument that established the definition of a child and enumerated the particular rights of children.

Countries that have ratified the treaty are routinely evaluated on their progress toward advancing child rights in their nation. As of 2020, the treaty has been ratified by every country in the world except for the United States of America; most of the ratifying countries have done so with “reservations and declarations.”

1999: The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act was passed, mandating that websites must include a privacy policy and take on certain responsibilities regarding the protection of children under 13 using their platform. Following the passage of the act, many operators have taken steps to prohibit children under 13 from using their websites due to the inherent costs of complying with the legislation.

In the same year, the International Labour Organization adopted the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, ratified by all countries, including the United States. The convention requires ratifying countries to immediately prohibit and eliminate the worst forms of child labor, defined as: all forms of slavery or similar practices; the commercial sexual exploitation of children; the use of children for illegal activities; or work that could potentially harm the health, safety, or morals of children.

The 21st Century

2002: The U.S. Senate unanimously consented to ratifying two optional protocols to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, even though it still did not ratify the convention itself. The two protocols were:

- the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography

- the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict

The U.S. did not sign the third, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a Communications Procedure.

2007: For the ninth time since the 106th Congress, Senator Dianne Feinstein introduced the Unaccompanied Alien Child Protection Act. The legislation would create an Office of Children’s Service within the U.S. Department of Justice, and amend an immigration system previously designed with adults in mind.

2011: Another landmark decision was handed down by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, a case regarding California law that prohibited the sale of violent video games to young people without the consent of their parents. In a win for the video game industry, the Court ruled that games were protected just like other media as a form of speech under the First Amendment.

Want to Learn More About Human Rights?

At the HeinOnline Blog, we love to research subjects of all shapes and sizes, including the immensely important topic of human rights. Check out our previous blogs on this topic, and then subscribe to the blog to receive posts like these right to your inbox.