The Medal of Honor is America’s highest military honor, awarded by the President in the name of Congress for extraordinary acts of valor. First presented in 1863 to the surviving Andrews Raiders, Union soldiers who volunteered to commandeer the Confederate train The General, the Medal of Honor has since been awarded more than 3,500 times. The criteria and design of the Medal has changed since 1863, and today three variants of the Medal exist: one for the Department of the Army (awarded to soldiers), one for the Department of the Navy (awarded to sailors, marines, and coast guardsmen), and one for the Department of the Air Force (awarded to airmen and Space Force guardians). Today, the greatest number of Medal of Honor recipients are from the American Civil War—including the only woman to date to receive the honor, Dr. Mary E. Walker. Join us during Women’s History Month, and just a week ahead of National Medal of Honor Day, as we explore history’s memory of this controversial figure.

Do you subscribe to the following databases? We’ll be using them throughout this post:

Humble Beginnings and a Looming Conflict

In 1832, on the shores of Lake Ontario in Oswego, NY, Mary Edwards Walker was born. Her parents were in many ways years ahead of their time. Abolitionists and advocates of women’s suffrage, the Walkers wanted their female children to have a full education equal to the one afforded to men, a radical idea for a time when women could not vote, and after marriage could not buy or sell their own property, keep their wages, sue, or gain legal custody of their own children. They also encouraged their daughters to dress however they saw fit, and young Mary adopted a hybrid wardrobe of men’s and women’s clothing.

Adulthood did not dampen Mary’s non-conformity. She continued to incorporate more pieces of men’s clothing into her everyday wardrobe until it completely supplanted dresses and corsets, a preference that would subject her to much ridicule for the rest of her life. In 1855, Mary graduated as a medical doctor from Syracuse Medical College, the only woman in her class. That same year, she married fellow medical student Albert Miller, but did not take his name; their subsequent medical practice, like their marriage, was short-lived, with the couple separating in 1859.

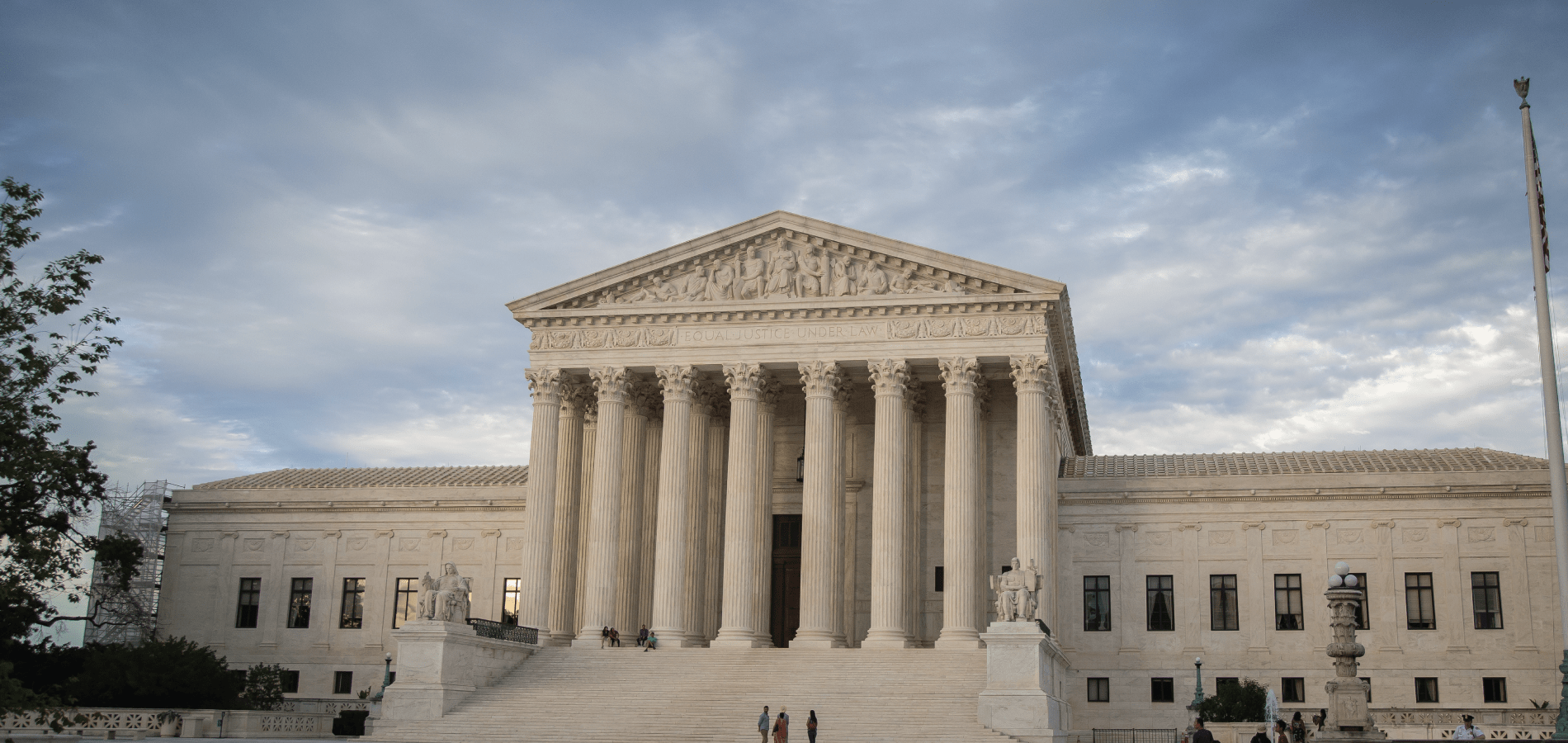

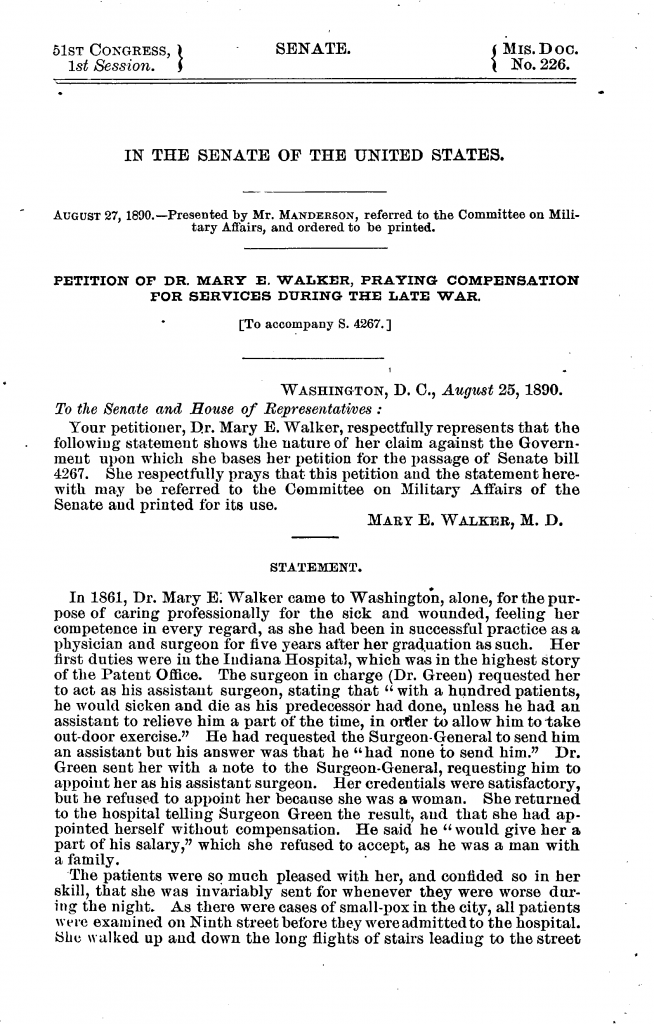

Fort Sumter fell to secessionists on April 13, 1861 and America fractured into the civil war it had been staving off fitfully for decades. With war officially declared between the states, Mary left her home and medical practice in Rome, NY and made the journey to Washington, D.C., where she applied to join the Union Army as a surgeon. Denied because of her sex, she stayed in the capitol working as an unpaid volunteer, first as a nurse and later as an assistant surgeon when the U.S. Patent Office was converted into a hospital, receiving a commendation from the head surgeon for being “an intelligent and judicious physician.”

Mary did not limit her work in Washington to only caring for the wounded warriors being transported in from the battlefield. As these injured men arrived in the city, so too did their wives, mothers, and sisters, all searching for loved ones. Often times, these women had nowhere to stay once they arrived in Washington, and so Mary began providing them what assistance she could, eventually establishing a home that provided them free food and lodging.

The War–and Mary–Persists

All while Mary worked in Washington, she continued petitioning the War Department to grant her a commission as a surgeon. When bureaucratic procedure wouldn’t let her work, she left Washington in 1862 and moved to Virginia to work at various field hospitals—again all unpaid—caring for wounded soldiers returning from the disastrous and ferocious Battle of Fredericksburg.

Nevertheless, she persisted in petitioning the Army for a commission as a surgeon, and her tenacity was finally rewarded in 1863 when she was employed as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon (civilian)” by the Army of the Cumberland, for the Union Army was collectively made up of multiple armies assigned to different fighting areas, such as the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Georgia. Within the Army of the Cumberland, Mary was assigned to the 52nd Ohio Infantry. She was held in high esteem by all her patients, and it was said that “they would ‘rather see her than any other lady, because she knew so much.”

Not restricting care to men in field hospitals, Mary frequently crossed battle lines to care for civilians. She was behind enemy lines in April 1864 when she was captured by Confederate troops. Suspected of being a spy because of her non-traditional clothing, she was imprisoned at Castle Thunder, a notoriously harsh Confederate prison within a converted tobacco warehouse in Richmond, Virginia. Mary was held at Castle Thunder for about four months until her release was secured in a prisoner exchange. A month after her release, she was back with the men of the 52nd Ohio, and later upon the recommendation of Major-Generals William T. Sherman and George Henry Thomas she was sent to work as an assistant surgeon at a women’s prison in Louisville, KY, where she stayed until May of 1865.

One War Ends, and Another Continues

The Civil War effectively ended on April 9, 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse, when Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant. With the war’s end, so too ended Mary’s time as a surgeon for the Army. Never afraid to speak up, Mary petitioned for the brevet rank of major, her previous contracted position being the modern equivalent of a lieutenant or captain. Her petition was denied.

But in “recognition of her services and sufferings,” President Andrew Johnson awarded her the “usual medal of honor for meritorious services” on November 11, 1865.

In some ways, the war had made Mary Walker as a doctor, elevating her out of little Rome, NY and onto the field of battle, with all its urgent and frightening need for quick, competent care, validating her skills and training. But the war had also ruined her health. Suffering from some kind of ocular atrophy or degeneration, attributed in her own opinion to the conditions she was subjected to as a prisoner of war, and now afflicted with poor health generally, Mary Walker struggled to provide for herself after the war. She petitioned the government multiple times from the 1870s into the 1890s, first for a war pension and then for subsequent increases to the pension with varying degrees of success; some reports found she had rendered “exceptionable services” while others claimed “her knowledge of medicine and surgery being very little, if any, more than that of the ordinary housewife.” Mary also assisted nurses and others in their petitions to the government for pensions, including testifying on behalf of a soldier she was imprisoned with at Castle Thunder.

Matters of Honor

In 1916, Congress established the Medal of Honor Review Board to review all previous medal recipients. Between 1861 and 1918, the Army had awarded 2,612 Medals of Honor and the Board was tasked with determining if all these recipients were worthy of the nation’s highest military honor. In the medal’s early days, criteria was less stringent, not codified, and in the absence of other decorations for valor, such as the Silver Star or Navy Cross, it was awarded more liberally. The Board’s recommendations helped form the basis of today’s criteria for awarding the Medal of Honor, emphasizing acts that risk life above and beyond the call of duty, barring civilians from being eligible, and instituting a time limit on when a recommendation for the medal can be made.

The Board’s final report to Congress in 1917 recommended revoking 911 medals—including Mary Walker’s on the grounds that she was not a member of the armed forces and because her services during the war did not involve any risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. Mary, however, refused to return her medal to Congress as instructed, and instead continued to wear it during all of her public appearances for the rest of her life. Mary Walker died two years later on February 21, 1919.

Some sixty years after her death, descendants of Mary Walker petitioned Congress to re-examine and restore her as a Medal of Honor recipient. At the urging of President Carter and some Members of Congress, the Department of Defense reviewed her case, with the Army Board for Corrections of Military Recordings ruling (with one dissent) that rescinding her award had been “unjust.” The Board noted that while no specific act of gallantry or heroism was noted in her award, had Mary been a man the Army certainly would have granted her a commission and her wartime service would have been considered that of a soldier. In 1977, Mary Walker’s Medal of Honor was officially restored, although not without continued controversy. Some have argued that rescinding the medal in 1917 had been the correct move, citing that she was not a member of the armed forces, had done nothing exceptional to warrant the award, and the government violated statutory time limits when it reinstated her medal. Women, of course, have always served their country, even when their country did not always formally acknowledge their service. Whether as camp nurses, hospital administrators, seamstresses, and even disguised to enlist as soldiers, they performed all these duties and more before their first formal integration into the military in 1901 with the creation of the Army Nurse Corps Auxiliary. As their roles within the modern armed forces continue to expand, it will only be a matter of time before Dr. Mary E. Walker is not the only woman to receive a Congressional Medal of Honor.

In Service of Knowledge

The HeinOnline Blog is a great place to learn about history’s famous and lesser-known figures, to get the scoop on political mishaps and misdeeds, and even go behind the scenes of our current pop culture moments. Check out our previous posts and subscribe to receive future posts straight to your inbox.