It was an unremarkable Independence Day in equally unremarkable Westbury, New York, a sleepy suburban village of approximately 15,000 souls in Long Island’s Nassau County. Westbury was a community prototypical of the post-war boom, a quiet place where everyone knew their neighbors, children played safely outside, and no one locked their doors at night. On that afternoon in 1956, Betty Weinberger sat on the patio of her modest ranch-style home with her one-month-old son, Peter, enjoying the summer air. She placed her sleeping son in his carriage on the patio and briefly stepped inside the house. But when she returned just a few minutes later, Peter was gone. Panicked and bewildered, she picked up a handwritten note that had been left behind.

Attention. I’m sorry this had to happen, but I am in bad need of money, and couldn’t get it any other way.

Don’t tell anyone or go to the police about this, because I am watching you closely. I am scared stiff, and will kill the baby, at your first wrong move.

Just put $2000 in small bills in a brown envelope and place it next to the sign post at the corner of Abermarle Road and Park Ave. at exactly 10 o’clock tomorrow (Thursday) morning. If everything goes smooth, I will bring the baby back and leave him in the same corner “safe and happy” at exactly 12 noon.

No excuses, I can’t wait!

The note was ominously signed, “Your baby sitter.”

Don’t miss out on the rest of the case. Follow the evidence found in these databases:

- History of Capital Punishment

- Law Journal Library

- U.S. Statutes at Large

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

- World Trials

A History of Crime

Peter Weinberger was certainly not the first child in America to be kidnapped for ransom. Twenty-four years prior, in 1932, the world had been shocked by the nighttime kidnapping of 20-month-old Charles Lindbergh, Jr. from the second floor of his parents’ home in East Amwell, NJ. A ransom note was left behind demanding $50,000 for the return of the famous aviator’s son. Despite a massive manhunt, worldwide attention, and complying with the kidnapper’s demands, the remains of Charles Lindbergh, Jr. were discovered some two months later. Bruno Richard Hauptmann was ultimately convicted as the perpetrator of the Crime of the Century, and was executed on April 13, 1936.

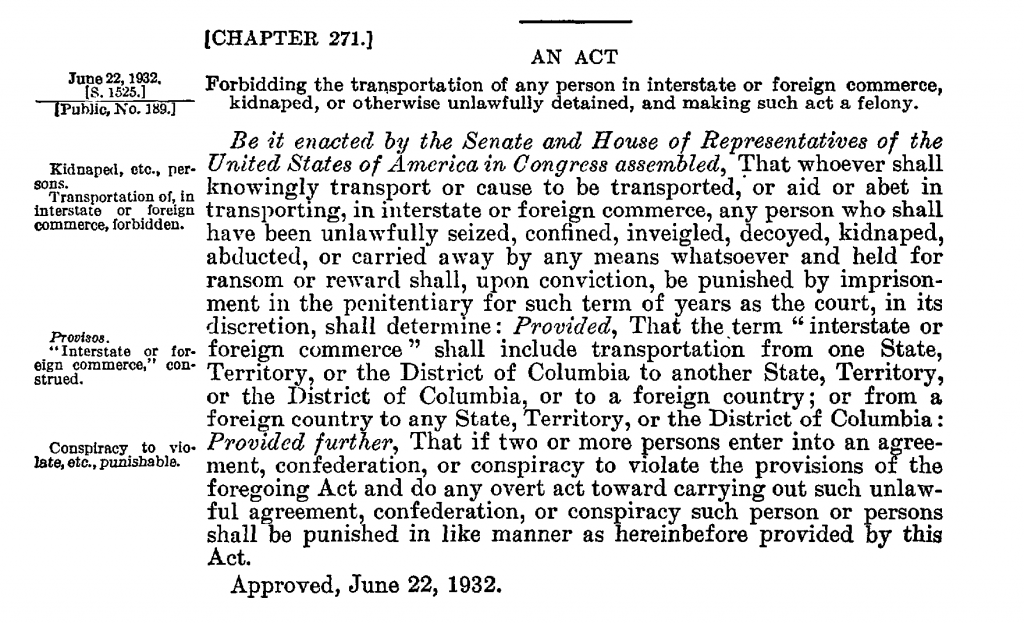

Spurred into action, Congress passed the Federal Kidnapping Act approximately three months after baby Lindbergh’s abduction. Popularly known as the Little Lindbergh Law, the Act allowed federal law enforcement to intervene in kidnapping cases once the parties had crossed state lines. Amendments to the law in 1934 added two important provisos to the Act’s reach: first, it changed the maximum penalty for kidnappers from life imprisonment to death, and secondly, it stated that if a kidnapped victim was not returned within seven days, the law would presume they had been trafficked across state lines, and federal authorities could intervene.

Unlike Lindbergh, Jr. and other famous kidnapped children, such as Adolphus Busch Orthwein, great-grandson to legendary brewer Adolphus Busch, or Charley Ross, the son of a prominent Philadelphian whose kidnapping had been a different century’s biggest criminal sensation, Peter Weinberger was not the progeny of famous or wealthy parents. His father, Morris, was a humble pharmacist. The amount demanded for Peter’s safe return, $2,000, is today roughly equivalent to $20,000: certainly a high ask for a middle-class family like the Weinbergers, but nowhere near the exorbitant sum demanded for Lindbergh, Jr. (equivalent to nearly $1 million in today’s currency). Who would risk the ultimate judicial punishment to kidnap an ordinary child from an ordinary family in a scheme to gain so little?

The Search—and Panic—Intensifies

Defying the kidnaper’s warning, the Weinbergers contacted law enforcement. Police asked the press to withhold coverage of Peter’s kidnapping for one day, until after the ransom had been paid, fearing front page headlines would scare off the perpetrator—or worse, drive him to harm Peter. The newspapers cooperated—except for the New York Daily News, which ran the story of Peter’s kidnapping in its evening edition. By the next morning, Peter’s kidnapping was on the front pages of all the New York papers. The shock of such a crime perpetrated on such ordinary people soon spread the story nationally; after all, if it could happen to the Weinbergers, if it could happen in the suburbs, in the middle of the afternoon, it could happen anywhere, to anyone.

Despite dropping the ransom at the appointed place and time, the money was never collected and, more importantly, Peter was not returned. Police held a press conference in which Betty Weinberger made an emotional appeal for her son’s return. Hoax calls began clogging the Weinbergers’ telephone line, but six days later, the kidnapper made contact. He ordered Morris to drive to a specific exit off Northern State Parkway, a major thoroughfare servicing Westbury and wider Nassau County, and leave the ransom there. When no one arrived to collect the money, the kidnapper again called the Weinbergers, changing the drop point to another exit down the parkway.

Waiting at the exit was a blue duffel bag with a second handwritten note containing instructions on where Peter could be found. But the note offered only false hope; Peter was not there. Police monitored the exit, hoping to catch the kidnapper as he collected the money, but no one arrived.

The discovery of the second note aligned with the end of the seven-day waiting period required by the Federal Kidnapping Act, and the FBI took over the case from the Nassau County Police Department. With the two ransom notes as their primary evidence, handwriting experts from the Bureau arrived on Long Island. They examined nearly 2 million public records from the New York area, such as motor vehicle and voter registrations, before stopping at a probation report filled out by Angelo John LaMarca, a 31-year-old taxi driver who had previously been arrested for bootlegging.

As had been the case in the “Crime of the Century,” the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., handwriting analysis was vital in identifying Peter Weinberger’s kidnapper. After comparing LaMarca’s known handwriting with the two ransom notes, FBI agents concluded LaMarca was their man, and he was arrested on August 23, 1956. After being taken into custody, LaMarca confessed, stating he had kidnapped and ransomed baby Peter in desperation after falling behind on his mortgage and into debt with a loan shark. He also revealed that the day after the first failed drop, scared by coverage in the press, he had abandoned Peter alive in heavy brush near another Northern State Parkway exit. The day after LaMarca’s arrest, agents found Peter’s remains in the spot LaMarca had indicated.

Peter’s Legislative Legacy

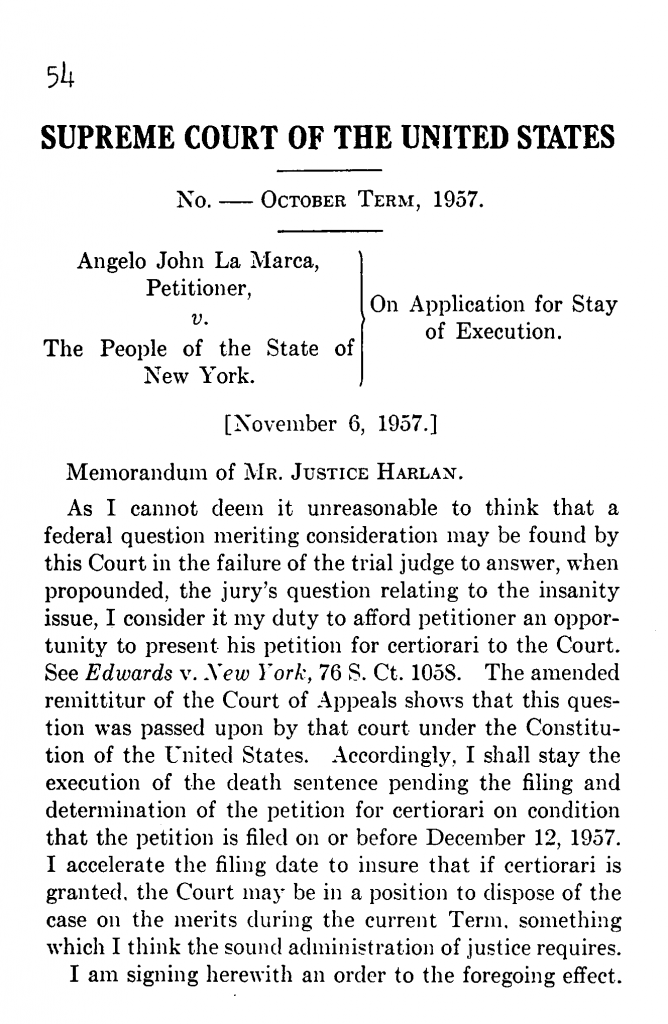

With LaMarca’s confession, investigators now knew that Peter had never been transported across state lines; therefore, with no jurisdiction, the FBI turned the case back over to local authorities. On December 14, 1956 LaMarca was found guilty of kidnapping and murder. He was sentenced to the same fate as Bruno Richard Hauptmann before him, to die in the electric chair. LaMarca vigorously appealed his conviction, eventually petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay of execution that was ultimately denied. Angelo LaMarca was executed at Sing Sing Prison on August 7, 1958.

As a direct result of the Peter Weinberger case, the Federal Kidnapping Act was amended in 1956 to allow the FBI to enter kidnapping investigations within 24 hours, as opposed to waiting seven days. Further reduction to this waiting period came in 1998 as part of the Protection of Children from Sexual Predators Act, which allowed federal involvement prior to the end of the 24-hour waiting period. In 1968, part of the Federal Kidnapping Act was declared unconstitutional in United States v. Jackson, when the Court held that the Act’s de facto punishment of death precluded a defendant’s right to a fair trial. While the punishment was altered, the Court did not strike down the entire Act, and it is still in force today.

Here at the HeinOnline blog, we strive to inspire researchers on myriad ways to use HeinOnline and its resources, whether the topic is strictly academic or ripped from the headlines. Subscribe now and never miss a post.