It’s not easy being a Swiftie. After a four-year break from touring, on November 1, 2022, Taylor Swift announced that she would again be hitting the road in her much-anticipated Eras Tour. Tickets would be sold via Ticketmaster, with special presales for registered Verified Fans and Capital One credit card holders.

The entire sale was, in short, a disaster on a scale similar to the Three Mile Island meltdown. Users attempting to buy tickets were sent to a virtual waiting room where they were told 2,000+ people were ahead of them in the queue. Tech-savvy Swifties were able to use a source code hack to reveal their true place in line, which was often 20,000 or more places back.

This was only the start of users’ frustrating experience. Less than an hour after presale began, Ticketmaster’s servers crashed, unable to handle the traffic demand; Ticketmaster later revealed traffic during the sale was 4x their previous peak. Accounts circulated on social media of users being booted from the frozen queue or being unable to complete the purchase of tickets in their cart.

Ticketmaster postponed the next day of presale to address these issues. Eventually, Ticketmaster canceled the public onsale “due to extraordinarily high demands on ticketing systems and insufficient remaining ticket inventory.” The company later reported that it sold 2 million tickets on the first day of presale, the most ever sold for an artist in a single day.

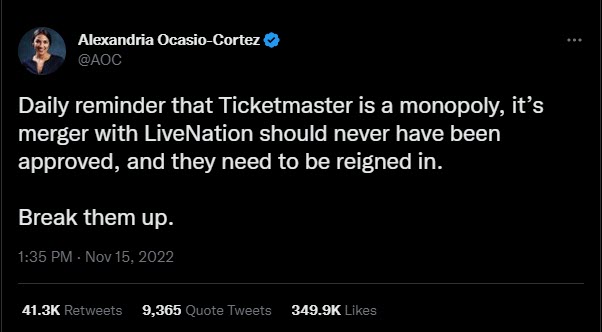

Outrage against Ticketmaster for its botched handling of Taylor’s tour was…swift. The bad blood wasn’t just limited to fans on Twitter; Capitol Hill took note of the fiasco, with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeting:

Days after the fiasco, the Department of Justice opened an investigation into Ticketmaster’s parent company, Live Nation Entertainment. Senators Amy Klobuchar and Mike Lee, who both serve on the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights, announced a congressional hearing would be held on the lack of competition in the ticketing industry. The hearing is set to take place on January 24th. Outside the federal government, the Attorneys General for Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Nevada, and North Carolina all announced investigations into the fiasco.

This isn’t the first time Ticketmaster has found itself in hot water. Using HeinOnline, let’s explore past Ticketmaster controversies to potentially gain insight into the current situation.

I Knew You Were Trouble

Anyone who has attempted to buy tickets to a popular event is familiar with how frustrating the process can be: you log in promptly at the onsale time, only to see the show is already sold out. If lucky enough to secure tickets, you are charged ridiculous “facility charges” and “service and convenience fees” that can nearly equal the ticket’s face value, leaving you wondering what, exactly, about this process was convenient.

Desperate ticketless fans may turn to the secondary market for a chance to score seats at the hottest show in town. Scalpers are hardly a modern invention; back in 1860,[1]Debra Parma, At Ticketmaster, Scalpers Score and Fans Come Last, 38 J.L. & Com. 463 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. when the hottest act in town was Charles Dickens’ speaking tour, scalpers resold tickets for ten times their face value.

But thanks to the internet, today scalpers armed with bots are able to buy thousands of tickets in minutes. At the height of Broadway smash hit Hamilton‘s popularity, for example, a single scalper managed to buy 30,000 tickets[2]Debra Parma, At Ticketmaster, Scalpers Score and Fans Come Last, 38 J.L. & Com. 463 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to the show off Ticketmaster; it was later revealed that 30–40% of Ticketmaster’s Hamilton inventory was bought by bots.

In the case of Taylor Swift | The Eras Tour, Ticketmaster claimed that less than 5% of tickets sold ended up on the secondary market. Ticketmaster has been accused of using its own bots to double dip on the secondary market, buying its own tickets to resell and getting paid on the convenience fees attached to the tickets on both their primary and secondary sale; Ticketmaster has always denied this practice.

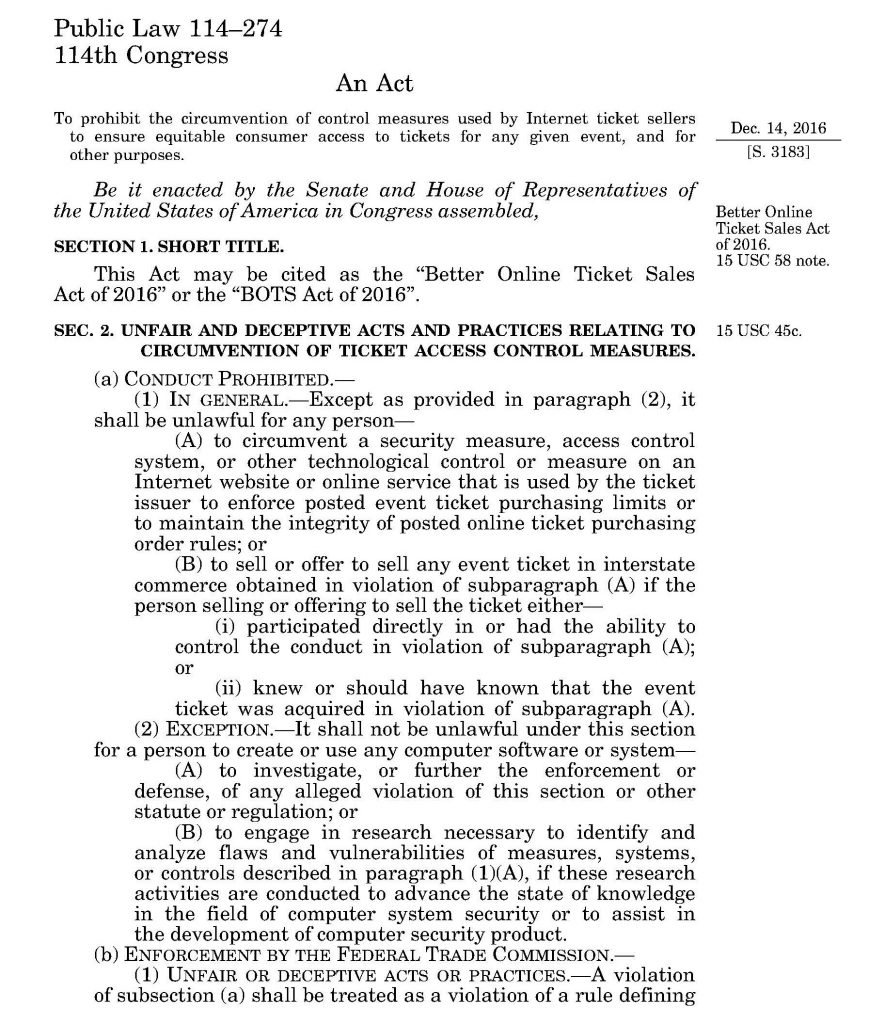

To try and address the bot problem, in 2016 Congress passed the Better Online Ticket Sales (BOTS) Act.[3]130 Stat. 1401. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. The Act makes it a crime to use “unfair and deceptive” means to circumvent security measures or purchase limits on online ticket sales. The Federal Trade Commission is charged with investigating any violations; since its enactment, the BOTS Act has been enforced three times.[4]Irini Christina Tsounakas, Fan to Fan, They’re Cheating You: American Fans’ Collective Nightmare and the Need for Uniform Regulation of America’s Secondary Ticketing Market, 50 Hofstra L. Rev. 969 (2022). This … Continue reading

But bots aren’t the only problem. In the case of the Taylor Swift | The Eras Tour controversy, many fans were shocked when the public ticket onsale was cancelled due to “insufficient inventory” and then bemused when Ticketmaster announced it would be selling a limited number of tickets to fans enrolled in the Verified Fans program who had been unable to buy tickets during the presale. Where had these tickets come from? And how had Ticketmaster managed to sell nearly its entire inventory during presale?

Band-Aids Don’t Fix Bullet Holes

Selling out in presale is not a uniquely Taylor Swift problem. In October 2021, mega boy band BTS immediately sold out its four shows at SoFi Stadium during fan presale.[5]Irini Christina Tsounakas, Fan to Fan, They’re Cheating You: American Fans’ Collective Nightmare and the Need for Uniform Regulation of America’s Secondary Ticketing Market, 50 Hofstra L. Rev. 969 (2022). This … Continue reading For reference, SoFi stadium has 70,240 seats and can expand its capacity to up to 100,240 for major events.

But venue size is not necessarily an indicator of how many tickets are available for sale. The concert promotor will hold back a certain number of tickets for presales, fan clubs, industry people, and dedicated credit card holder sales. Fans may be shocked to learn how many of these tickets are actually held back; a 2016 investigation by New York’s Attorney General found that, on average, 16% of available tickets are held aside for insiders, with another 38% held for presale.

An investigation by New Jersey’s Attorney General into Ticketmaster’s disastrous handling of Bruce Springsteen’s Working on a Dream Tour—where fans attempting to use Ticketmaster to purchase tickets were instead redirected to Ticketmaster’s resale subsidiary, TicketNow, to purchase tickets at four times their face value[6]Erik Holmstrom, Dancing in the Dark: An Analysis of the Live Entertainment Industry and the Deceptive Market Practices of Ticketmaster and Live Nation, 9 W. J. Legal Stud. 1 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law … Continue reading—uncovered similarly alarming statistics. The report concluded that “of the 38,788 seats made available for the two shows…only 6,000 people were able to buy tickets.” 10,494 tickets were set aside for insiders and the remaining inventory was sent to secondary ticketing sites.[7]Erik Holmstrom, Dancing in the Dark: An Analysis of the Live Entertainment Industry and the Deceptive Market Practices of Ticketmaster and Live Nation, 9 W. J. Legal Stud. 1 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law … Continue reading

To attempt to regulate the secondary ticket market, in 2019 the Better Oversight of Secondary Sales and Accountability in Concert Ticketing Act was introduced in the House of Representatives. Among other things, the act would require ticket vendors to disclose the total number of tickets offered for sale for a given event and require that secondary ticket marketplaces disclose any associations with the primary seller, artist or venue. The 2019 iteration of the act is the latest version of a bill that has been kicking around Capitol Hill for a decade. It has yet to be passed.

It’s Me, Hi. I’m the Problem, It’s Me

Event goers looking to circumvent a terrible ticket-buying experience may want to patronize another vendor for all their ticketing needs. Competition in this area, however, is lacking, and people often have no choice but to use Ticketmaster.

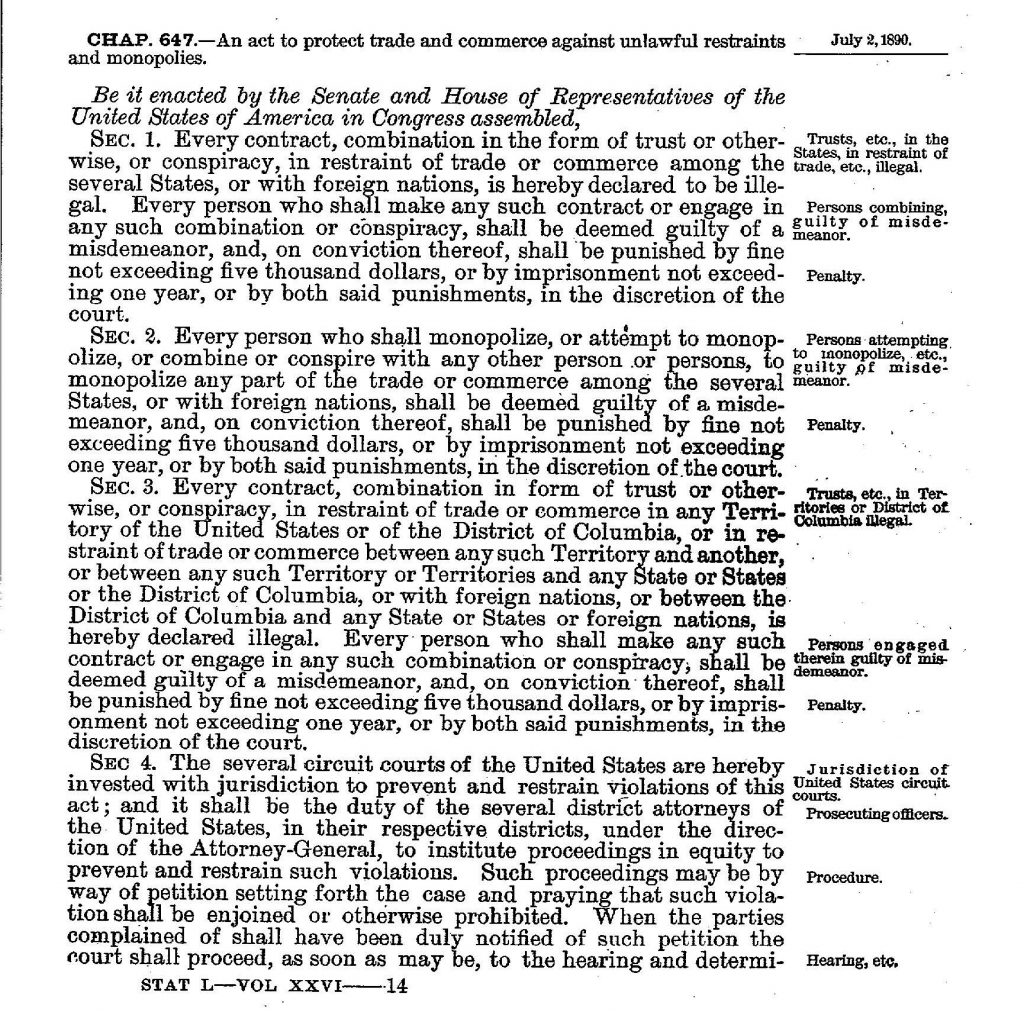

Readers may remember from their high school history classes learning about the Sherman Anti-trust Act.[8]26 Stat. 209 (1890). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. Passed in 1890, it was the first antitrust act passed in the United States. Its purpose was to “protect trade and commerce against unlawful restraints and monopolies” and punish those who engage in the “restraint of trade or commerce.” The act was dubbed by one scholar as “the Magna Carta of free enterprise.”[9]Joycelyn Stevenson, Changes in the Ticket Distribution Industry: Is This the Beginning of the End for Ticketmaster, 3 Vand. J. Ent. L. & Prac. 53 (2001). Particularly astute students might remember that the Sherman Anti-trust Act was invoked by the U.S. Supreme Court to dissolve mega-monopoly Standard Oil Company in Standard Oil Co. v. United States.[10]221 U.S. 1. This case is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library.

The Sherman Anti-trust Act received additional regulatory teeth from the Clayton Act, passed in 1914. The Clayton Act was intended to prevent unlawful corporate mergers and acquisitions, enforced by the then newly created Federal Trade Commission. Both Acts are still in effect today.

In 2010, Ticketmaster and Live Nation merged to create Live Nation Entertainment, Inc. America’s leading ticketing company and the world’s largest concert promotor—and itself a ticket seller—were one. The merger brought together ticket sales, concert promotion, venue management, and other live event ventures under one mega umbrella. In a 2009 hearing on the proposed merger, it was estimated that Ticketmaster controlled roughly 70-80%[11]The TicketMaster/Live Nation merger : what does it mean for consumers and the future of concert business? : hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States … Continue reading of all concert ticket sales prior to the merger.

Despite concerns from lawmakers and artists alike over what such a merger would mean for the business, it was ultimately approved by the Justice Department. No artists appeared before Congress to testify against the merger.[12]Competition in the Ticketing and Promotion Industry: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Courts and Competition Policy of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session. This hearing is found in … Continue reading

It was hardly the first controversal acquisition in Ticketmaster’s history. In 1991, the company purchased Ticketron, then its closest competitor; one of Ticketmaster’s first moves was to dramatically increase Ticketron’s standard $1 service fee.

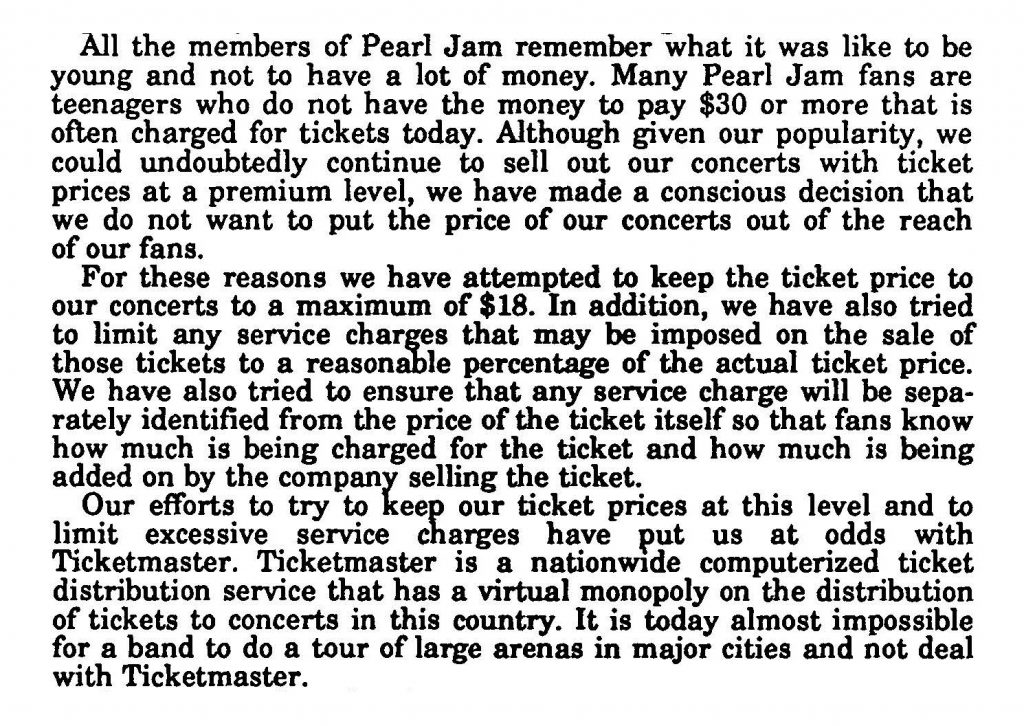

For Pearl Jam’s 1993 summer tour, the band requested Ticketmaster separately list its service fees on tickets,[13]Joycelyn Stevenson, Changes in the Ticket Distribution Industry: Is This the Beginning of the End for Ticketmaster, 3 Vand. J. Ent. L. & Prac. 53 (2001). to help fans better differentiate the cost the band was charging for tickets versus the fees Ticketmaster was appending. The band also took umbrage with Ticketmaster’s exclusivity deals with major venues and promotors. Unable to compromise, the band canceled its tour, filed a complaint against Ticketmaster with the Justice Department, and took its grievances before the House Committee on Government Operations.[14]Pearl Jam’s Antitrust Complaint: Questions about Concert, Sports, and Theater Ticket Handling Charges and Other Practices. This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. Stone Gossard, the band’s guitarist, and Jeff Ament, the band’s bassist, pled the band’s case before Congress.

Also testifying before the House Committee were representatives from Aerosmith, R.E.M., and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Aerosmith’s manager, Tim Collins, relayed to the Committee that Steven Tyler, the band’s lead singer, said of Ticketmaster, “Mussolini may have made the trains run on time, but not everyone could get a seat on the train.”[15]Pearl Jam’s Antitrust Complaint: Questions about Concert, Sports, and Theater Ticket Handling Charges and Other Practices. This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. Despite pressure from Pearl Jam, ultimately nothing meaningful was done at the federal level about Ticketmaster’s business practices.

Only time will tell if the righteous fury of aggrieved Swifties and the Justice Department’s current probe into Ticketmaster will have any impact on the current ticketing landscape. If you failed to buy tickets to the Eras Tour, at the time of this writing there were still dozens of tickets available on StubHub. The median price to sit in the 300 level at MetLife Stadium, for example, was $1,000 per ticket.

BLASE a Trail through HeinOnline

Did you know HeinOnline has an entire collection devoted to sports and entertainment law? Our Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment database (or BLASE as we fondly call it) won the prestigious Joseph L. Andrews Legal Literature Award and features more than 9,000 topically-arranged periodical articles. Learn more about all the great content in BLASE by visiting its dedicated LibGuide.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑2 | Debra Parma, At Ticketmaster, Scalpers Score and Fans Come Last, 38 J.L. & Com. 463 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | 130 Stat. 1401. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑4, ↑5 | Irini Christina Tsounakas, Fan to Fan, They’re Cheating You: American Fans’ Collective Nightmare and the Need for Uniform Regulation of America’s Secondary Ticketing Market, 50 Hofstra L. Rev. 969 (2022). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6, ↑7 | Erik Holmstrom, Dancing in the Dark: An Analysis of the Live Entertainment Industry and the Deceptive Market Practices of Ticketmaster and Live Nation, 9 W. J. Legal Stud. 1 (2019). This article is in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | 26 Stat. 209 (1890). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑9, ↑13 | Joycelyn Stevenson, Changes in the Ticket Distribution Industry: Is This the Beginning of the End for Ticketmaster, 3 Vand. J. Ent. L. & Prac. 53 (2001). |

| ↑10 | 221 U.S. 1. This case is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑11 | The TicketMaster/Live Nation merger : what does it mean for consumers and the future of concert business? : hearing before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, first session, February 24, 2009. This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑12 | Competition in the Ticketing and Promotion Industry: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Courts and Competition Policy of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session. This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑14, ↑15 | Pearl Jam’s Antitrust Complaint: Questions about Concert, Sports, and Theater Ticket Handling Charges and Other Practices. This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |