Black history is filled with heroes who have overcome unspeakable obstacles in the fight for racial equality, civil rights, and social justice. Every day, and especially this month, these leaders serve as inspiration for the ongoing struggle in the Black community in the face of police brutality, economic disparities, and other inequities.

In this blog post, we use HeinOnline to explore five Black leaders who you may not have heard of, or know much about, to illustrate some of the rich and often untaught history of Black America.

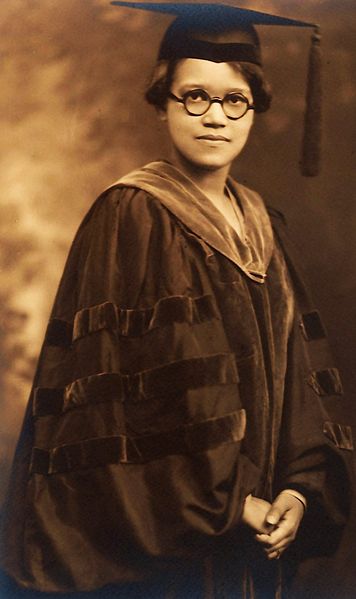

1. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

A Leader in Law

Born in Philadelphia in 1898, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander’s father was the first Black person to graduate from Penn’s Law School, a perfect foreshadowing of the strides that Alexander would make in the legal world during her own lifetime. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Education, Alexander then entered the graduate school there to study economics, and in 1921 she became one of only three Black women in the United States to have earned a Ph.D. —her dissertation was titled “The Standard of Living Among One Hundred Negro Migrant Families in Philadelphia.” Then, in 1924, Alexander entered the University of Pennsylvania’s law school, where she became the first Black woman to graduate the program as well as the first Black woman to be admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar.[1]Damon T. Hewitt, Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: The Legacy of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, A , 16 NAT’l BLACK L.J. 109 (1998). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

After graduating, Alexander joined her husband’s law practice, specializing in estate and family law. She went on to serve as Assistant City Solicitor for the City of Philadelphia, while also participating on a variety of boards and committees locally and nationally. She served as the national secretary of the National Bar Association in 1943, and was selected by President Truman for his Committee on Civil Rights[2]Charles Lewis Nier II., Sweet Are the Uses of Adversity: The Civil Rights Activism of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, 8 TEMP. POL. & CIV. Rts. L. REV. 59 (1998). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s … Continue reading in 1947, which would encourage him to federally outlaw lynching and protect the right to vote. Additionally, Alexander was part of the Commission on Human Relations in Philadelphia from 1953 to 1968, and she was named to the Court of Common Pleas in that city in 1959. President Jimmy Carter appointed her chair of the White House Conference on Aging in 1978, a little more than a decade before her death in 1989.

2. Howard Thurman

Inspiration to Martin Luther King, Jr.

Howard Thurman was born on November 18, 1899 in Daytona Beach, FL. After high school, he attended Morehouse College and Colgate Rochester Divinity School, and at both institutions he excelled in his studies. After graduating, he served as Director of Religions Life at Morehouse and Spelman Colleges in Atlanta, and he was the first dean of Andrew Rankin Chapel at Howard University. In 1935, Thurman and his wife led a Black delegation to Southeast Asia. It was on this trip that Thurman met Mohandas Gandhi, who taught him about nonviolent protest.[3]113 Cong. Rec. 23214 (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.

Thurman went on to cofound the interracial Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, before being recruited by Boston University to serve as the Dean of Marsh Chapel, making him the first Black dean at a mainly white university. It was at Boston University that Thurman would interact with other future Black leaders, including James Baldwin and Martin Luther King Jr.[4]Stewart Burns, Editor. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1997). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. In fact, Thurman was a friend and classmate of MLK Jr.’s father. Thurman deeply influenced the civil rights leader’s nonviolent approach during the Civil Rights movement. Additionally, Thurman wrote a number of renowned books, including Jesus and the Disinherited.[5]Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr., An Awakening: How the Civil Rights Movement Helped Shape My Life, 59 N.Y. L. Sch. L. REV. 59 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. He was recognized by many as a deeply influential spiritual and nonviolent leader.

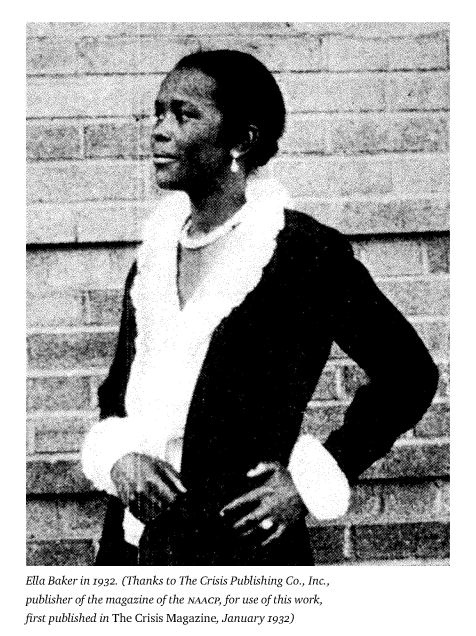

3. Ella Baker

Civil Rights Leader

Born on December 3, 1903 in Norfolk, VA, Ella Baker came from a grandmother who had been enslaved and brutally punished for refusing to marry the man selected for her by her slave owner. This brave resistance served as a constant inspiration for Baker. Her grandparents bought and lived on land that was part of the plantation where they had formerly been enslaved. Baker studied at Shaw University in Raleigh, NC,[6]Barbara Ransby. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database. and after graduating she moved to New York City, where in 1930 she joined the Young Negroes Cooperative League, along with several organizations focused on women’s issues. In 1940, Baker began working with the NAACP,[7]Barbara Ransby. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database. and she eventually earned a role as director of branches, in which she served from 1943 to 1946.

In 1955, she cofounded an organization committed to raising money to combat Jim Crow laws, and in 1957 she moved down to Atlanta and worked with Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[8]Barbara Ransby. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database. Eventually, she left the SCLC and organized the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC)[9]Barbara Ransby. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database. alongside the students who led the Greensboro sit-ins. With the SNCC, Baker worked with the Congress of Racial Equality to organize the 1961 Freedom Rides, as well as the Freedom Summer voter registration drive in Mississippi.

Because of her achievements and commitment to working with students and young people, Baker earned the nickname “Fundi,” which in Swahili means a person who teaches a skill to the next generation.

4. Marsha P. Johnson

LGBTQ+ Rights Advocate

Born Malcolm Michaels Jr. on August 24, 1945 in Elizabeth, NJ, Johnson began wearing dresses as a child, but suffered relentless bullying by local boys and was sexually assaulted when she was 13. After graduating high school, she relocated to New York City, taking only $15 and a bag of clothes with her. In the City, she relied on sex work to survive and was subsequently arrested several times. She soon became a drag queen, wearing extravagant outfits that she created from items she found in thrift stores. She renamed herself Marsha P. Johnson, with the P standing for “Pay It No Mind,” which was the retort she would give when asked about her gender. Johnson soon became a prominent figure in the LGBTQ community, as she worked to help support LGBTQ youth. She was also photographed by Andy Warhol as part of his “Ladies and Gentleman” series. Diagnosed with HIV, Johnson also became an advocate for those with AIDS.[10]Movement Lawyering in Moments of Crisis: Some Things White Allies (and Others) Can Do, 46 HUM. Rts. 22 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

You never completely have your rights, one person, until you all have your rights.

On June 28, 1969, police raided Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street, a safe haven for the gay community. Johnson has denied starting the uprising that soon followed,[11]Shana Marks, No Pride without Protest: How the Black LGBTQ Community Changed History, 10 Young Advocs. 4 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. but she did participate, and many credit her with being a primary figure in the gay liberation movement. She joined the Gay Liberation Front and marched in the first Gay Pride rally, and along with her close friend Sylvia Rivera, she cofounded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR)[12]Movement Lawyering in Moments of Crisis: Some Things White Allies (and Others) Can Do, 46 HUM. Rts. 22 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to help homeless transgender youth in big cities.

In 1992, Johnson’s body was found in the Hudson River, and her death was initially deemed a suicide, but those close to her denied that she was suicidal, and her case was reopened 25 years later and remains open today.

5. Jane Bolin

First Black Female Judge

Jane Bolin was born to an interracial couple on April 11, 1908, in Poughkeepsie, NY. After graduating high school early, she attended Wellesley College and was recognized as a top student. She went on to become the first Black woman to earn a law degree from Yale.[13]Willie J. Epps Jr. & Jonathan M. Warren, Sheroes: The Struggles of Black Suffragists, 59 Judges J. 10 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. After graduating, she worked at her family’s law practice, and she relocated to New York City after marrying. She served as an assistant corporate counsel in the City, becoming the first Black woman to hold that title. At the World’s Fair in 1939, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia surprised Bolin by swearing her in as a judge, making her the first Black female judge in the United States.[14]Willie J. Epps Jr. & Jonathan M. Warren, Sheroes: The Struggles of Black Suffragists, 59 Judges J. 10 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. She was assigned to family court, where she worked for four decades fighting against segregationist policies and supporting the welfare of children.[15]Patria Frias-Colon & Irwin Weiss, Judge Jane Bolin: Ahead of the Times, Part II: A Look at Her Child Support Cases, 55 FAM. L.Q. 281 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Additionally, she served on the board of the NAACP and the New York Urban League.

Further Your Research with HeinOnline’s Social Justice Suite

With databases including Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law as well as Civil Rights and Social Justice, HeinOnline’s perpetually free Social Justice Suite is the perfect resource for studying Black history and its heroes. To learn more about the Social Justice Suite and how you can register for this resource for your institution for free, check out our dedicated webpage.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Damon T. Hewitt, Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: The Legacy of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, A , 16 NAT’l BLACK L.J. 109 (1998). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Charles Lewis Nier II., Sweet Are the Uses of Adversity: The Civil Rights Activism of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, 8 TEMP. POL. & CIV. Rts. L. REV. 59 (1998). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | 113 Cong. Rec. 23214 (1967). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑4 | Stewart Burns, Editor. Daybreak of Freedom: The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1997). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. |

| ↑5 | Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr., An Awakening: How the Civil Rights Movement Helped Shape My Life, 59 N.Y. L. Sch. L. REV. 59 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6, ↑7, ↑8, ↑9 | Barbara Ransby. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law database. |

| ↑10, ↑12 | Movement Lawyering in Moments of Crisis: Some Things White Allies (and Others) Can Do, 46 HUM. Rts. 22 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | Shana Marks, No Pride without Protest: How the Black LGBTQ Community Changed History, 10 Young Advocs. 4 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s ABA Law Library Collection Periodicals database. |

| ↑13, ↑14 | Willie J. Epps Jr. & Jonathan M. Warren, Sheroes: The Struggles of Black Suffragists, 59 Judges J. 10 (2020). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15 | Patria Frias-Colon & Irwin Weiss, Judge Jane Bolin: Ahead of the Times, Part II: A Look at Her Child Support Cases, 55 FAM. L.Q. 281 (2021). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |