Top o’ the morning to ya! Are you feeling lucky? Because today we’re going to shamrock your world with some St. Patrick’s Day facts that will make you feel like you’ve struck gold. From leprechauns to corned beef, get ready to jig your way into a wealth of information about this beloved Irish holiday. So grab a pint of Guinness and let’s dive into some unforgettable St. Patrick’s Day knowledge.

1. St. Patrick Wasn’t Irish

Contrary to what most people think, St. Patrick was not actually born in Ireland. While his life is a blend of mythology and folklore, most historians believe he was born near the end of the 4th century in Britain.[1]Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland (1850). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. In fact, St. Patrick was captured and sold into slavery in Ireland. He eventually escaped back to Britain, but returned years later as a Christian missionary. Here, he even visited his former owner, Milcho.[2]Martin Haverty. History of Ireland, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (1867). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. After spending years preaching Christianity and becoming a bishop, he eventually died in Ireland on March 17. A.D. 493.

2. St. Patrick’s Name Wasn’t Patrick

Not only was St. Patrick not Irish, but his name wasn’t actually Patrick. His name, as recorded at his baptism, was Succoth,[4]Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland (1850). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. which signifies valiant in war. In the year 432, after becoming a priest, he changed his name to Patricius,[5]John Laurence; Murdock Von Mosheim, James, et al., Editors, Translators. Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern (1863). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. otherwise known as Patrick, which in Latin means “father.”

3. Leprechauns Are Fairies

The iconic image of the red-haired, green-clad leprechaun is one we often find associated with St. Patrick’s Day, or on the box of our Lucky Charms. However, leprechauns are believed to have originated from the Celtic belief in fairies,[6]James; et al. Hastings, Editors. Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics (1962). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. which were thought to be tiny beings with magical abilities to cause mischief or perform good deeds. In Celtic folklore, leprechauns were portrayed as grumpy individuals whose job was to fix the shoes of other fairies. What’s more, the infamous Irish leprechaun has said to have been heard wailing “a cry of piercing sorrow“[7]George Potter. To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database when a person was nearing death as a notice to the family.

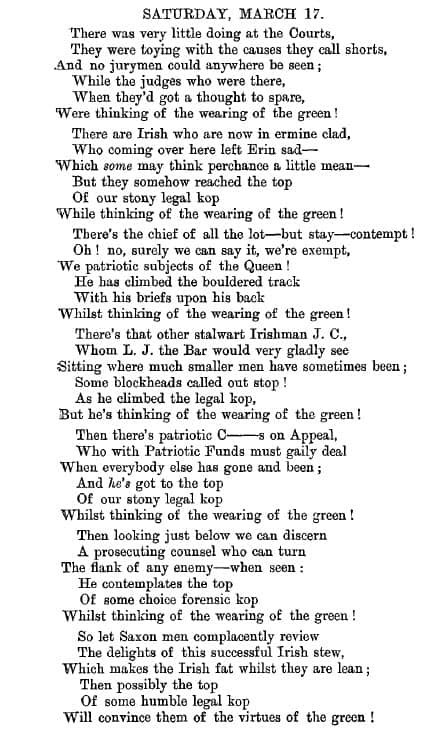

4. Green Is the New Blue of Ireland

This St. Patrick’s Day you’ll find swarms of people wearing various colors of green even though the official color of Ireland is blue, azure blue to be exact. Today as it stands, Ireland’s coat of arms is colored azure blue with a gold harp and silver strings.[8]John Rooney. Genealogical History of Irish Families, with Their Crests and Armorial Bearings (1900). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics library. It wasn’t until later that green became the color of Ireland. The color green can be contributed to a few different pieces of history. It was first used to show support for Ireland during the Great Irish Rebellion in 1641, when Catholic landowners and bishops were forced out by the English government. “The Wearing of the Green” is an Irish folk song that mourns the repression of Irish Rebellion of 1798 and highlights the fact that people were being executed for simply wearing the color green, which was the chosen hue of the revolutionary Society of United Irishmen, whose members adorned themselves with green clothing, ribbons, or cockades.[9]William Edward Hartpole Lecky. History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (1913). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database.

5. The Shamrock Was a Sacred Plant

The shamrock is often attributed to St. Patrick because while in Ireland he used it as an illustration of the Holy Trinity:[11]Thos. W. H. Fitzgerald. Ireland and Her People: A Library of Irish Biography Together with a Popular History of Ancient and Modern Erin (1910). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. the belief that God the Father, Jesus the Son, and the Holy Spirit are one and the same. Shamrocks are also the reason Ireland has often been referred to as the “Emerald Isle“[12]Portions of Information, on Some of the Most Important Parts of the English Constitution; and upon Prominent Events in British History (1834). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. due to its green landscape. Furthermore, it was a custom of Irish soldiers to conceal on their bodies bunches of shamrock[13]James Grant. Mysteries of All Nations: Rise and Progress of Superstition, Laws against and Trials of Witches, Ancient and Modern Delusions, Together with Strange Customs, Fables and Tales (1880). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s … Continue reading in hopes of securing success. And forget engagement rings—in old Irish times, people exchanged shamrocks as a sign of commitment to their lover.

6. Corned Beef Originated in New York City

In Ireland, ham and cabbage were more often consumed; however, corned beef was a cheaper solution for Irish immigrants living in Manhattan in the late 19th century. Irish immigrants largely purchased their meat from kosher butchers, resulting in what is now commonly known as Jewish corned beef.[14]William V. Shannon. American Irish (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database. Jewish immigrants prepared corned beef using brisket, a kosher meat cut from the front of the cow, which, due to its toughness, required salting and cooking to transform it into the incredibly tender and flavorful corned beef we enjoy today.

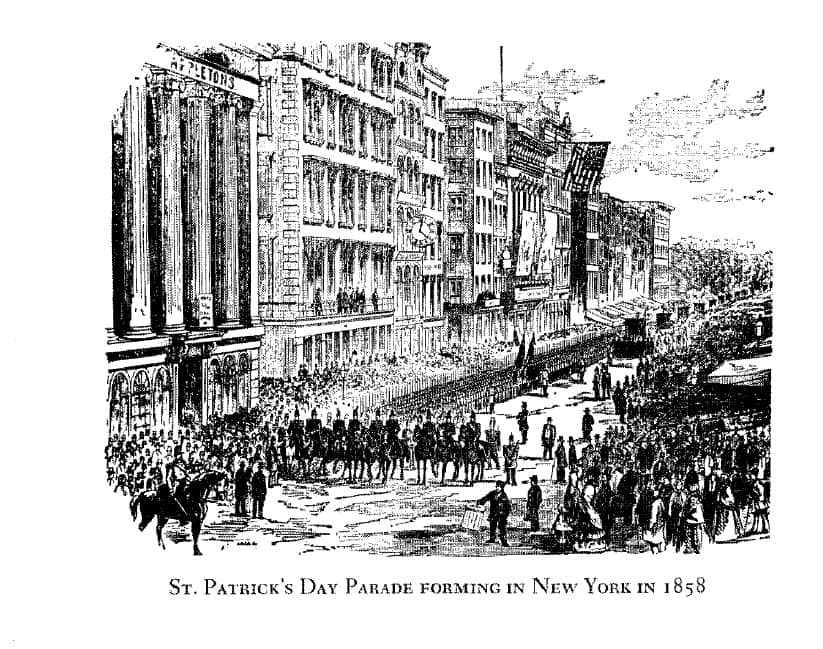

7. The First St. Patrick’s Day Parade Was Held in Florida

Okay, so at the time it wasn’t Florida, but the first recorded parade[15]1 12 (2021)

Brief Amici Curiae of City and County of San Francisco, et al. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases honoring the Catholic feast day of St. Patrick was held on March 17, 1601 in a Spanish colony which is now considered St. Augustine, Florida. Then, in 1797, the first parade in the first thirteen colonies[16]George Potter. To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database was held in Boston. By 1848, the St. Patrick’s Day parade became the largest parade not only in the United States, but the world.

May your knowledge grow and your research be sound,

May you always find what needs to be found.

May your HeinOnline subscription be a valuable tool,

And may our blog help you to never be a fool.

Sláinte!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1, ↑4 | Life of Saint Patrick, Apostle of Ireland (1850). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3 | Martin Haverty. History of Ireland, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time (1867). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. |

| ↑5 | John Laurence; Murdock Von Mosheim, James, et al., Editors, Translators. Institutes of Ecclesiastical History, Ancient and Modern (1863). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. |

| ↑6 | James; et al. Hastings, Editors. Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics (1962). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. |

| ↑7, ↑16 | George Potter. To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America (1960). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database |

| ↑8 | John Rooney. Genealogical History of Irish Families, with Their Crests and Armorial Bearings (1900). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics library. |

| ↑9 | William Edward Hartpole Lecky. History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (1913). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. |

| ↑10 | https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/lawtms108&i=501. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | Thos. W. H. Fitzgerald. Ireland and Her People: A Library of Irish Biography Together with a Popular History of Ancient and Modern Erin (1910). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. |

| ↑12 | Portions of Information, on Some of the Most Important Parts of the English Constitution; and upon Prominent Events in British History (1834). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitution Illustrated database. |

| ↑13 | James Grant. Mysteries of All Nations: Rise and Progress of Superstition, Laws against and Trials of Witches, Ancient and Modern Delusions, Together with Strange Customs, Fables and Tales (1880). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Religion and the Law database. |

| ↑14 | William V. Shannon. American Irish (1963). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. database. |

| ↑15 | 1 12 (2021) Brief Amici Curiae of City and County of San Francisco, et al. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases |