2023 marks the 160th anniversary of not only the most famous battle of the American Civil War, but one of the most famous military conflicts in all of American history: the Battle of Gettysburg. Fought over three days across Pennsylvania farmland, Gettysburg was the war’s turning point and its single bloodiest battle. Using HeinOnline, let’s unlock this pivotal moment in military history.

Before the Battle

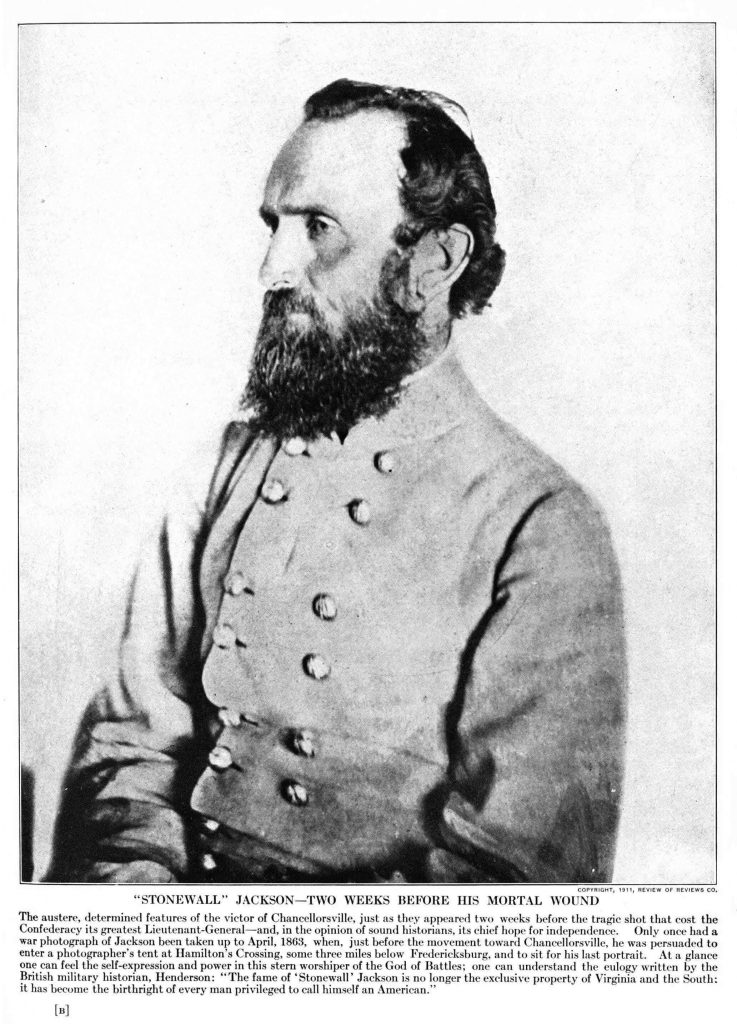

Confederate general Robert E. Lee was riding high after his victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville[1]Bradford A. Wineman. Chancellorsville Campaign, January-May 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. in May, 1863. Chancellorsville is considered to be Lee’s “perfect battle” because of his risky but successful tactic to divide his much-smaller Army of Northern Virginia against Union general Joseph Hooker’s massive Army of the Potomac. But victory came at a high price. At the battle’s end, more than 30,000 Confederate and Union soldiers were dead or wounded, including Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Lee considered Jackson to be “the right arm of the whole army,”[2]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. and his death was an unquantifiable loss.

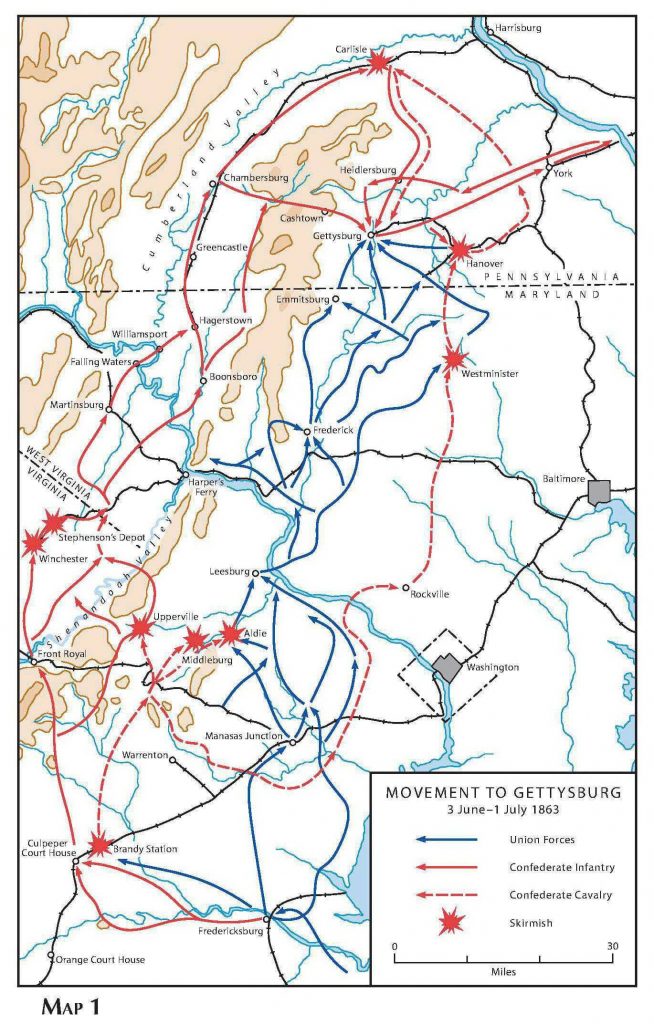

Despite Jackson’s death, Lee’s victory emboldened him to once again attempt to invade the North. Aside from the obvious advantage of a successful Northern invasion, it was also hoped it would redirect Union forces away from the port city of Vicksburg, Mississippi,[3]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. which was currently under siege by Union general Ulysses S. Grant.

By mid-June, the Confederates had crossed the Potomac River and entered Maryland. They raided and looted civilian homes for supplies along the way. Between 40 to 60 free Black men, women, and children were rounded up by Confederate troops and marched southward into slavery. On June 26, 1863, Lee’s army arrived in the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

On June 28, President Abraham Lincoln removed Hooker as the commander of the Army of the Potomac and replaced him with Maj. General George G. Meade. The change was so abrupt[4]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. that Meade wasn’t even provided with intelligence on where Lee and his troops were located. Still, he sent the Union army across the Potomac after Lee’s general direction, with Union cavalry arriving south of Gettysburg on June 30.

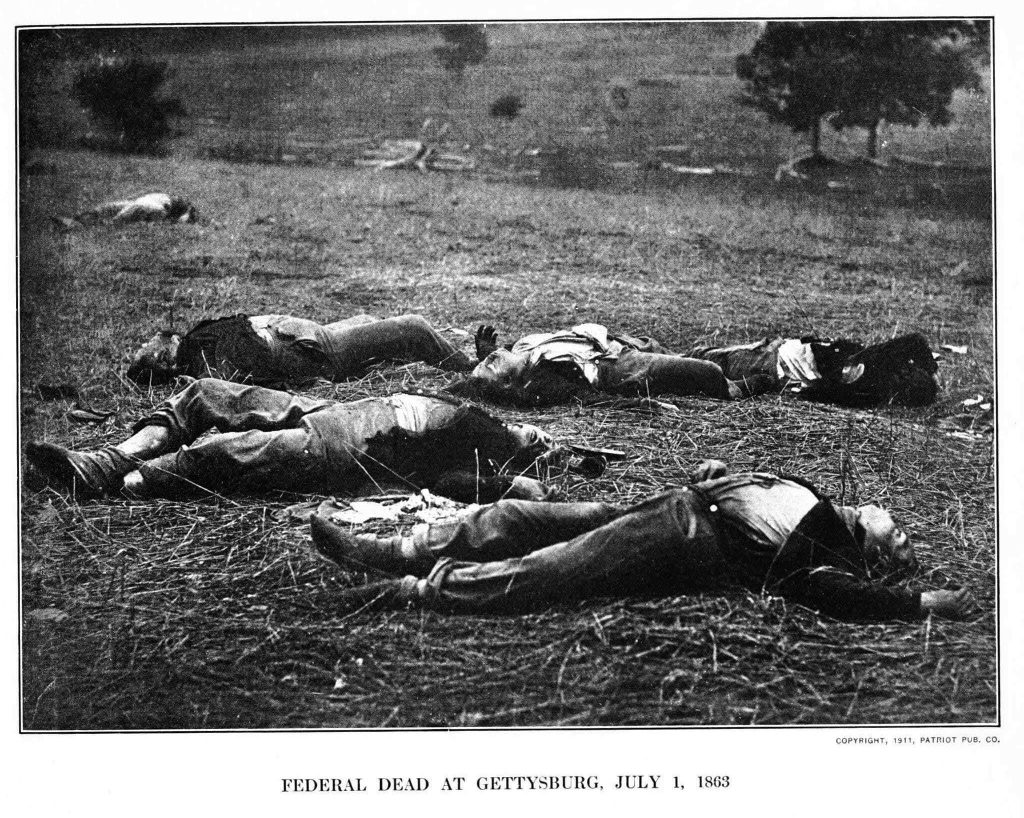

The First Day: July 1, 1863

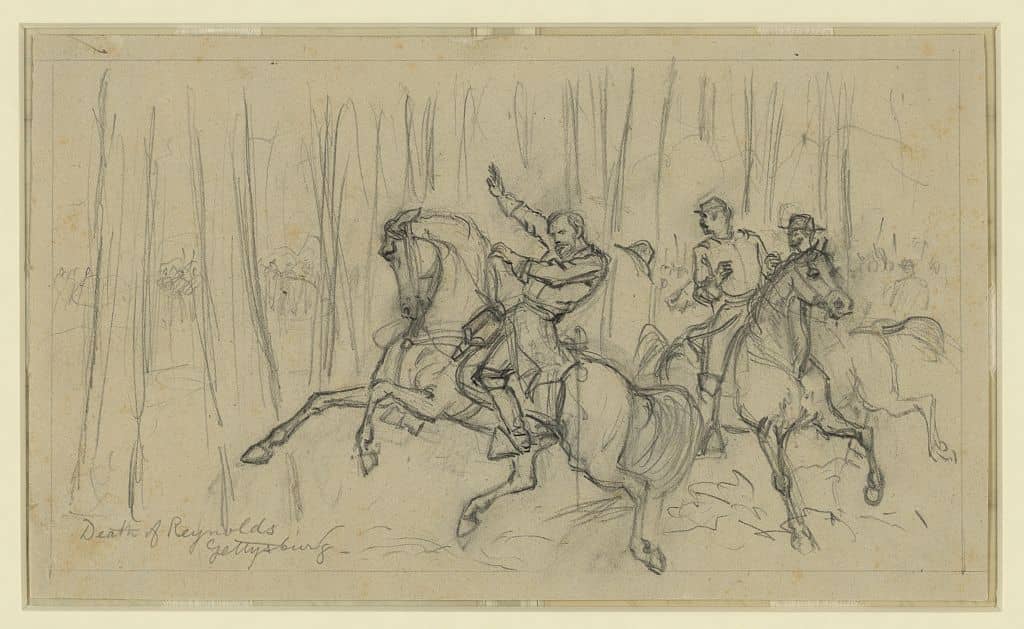

Tradition credits Union Lt. Marcellus Jones[5]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. with firing the first shot of the battle of Gettysburg. Jones was serving in Brig. General John Buford’s division, and Buford immediately sent word to Meade about the 14,000 Confederate troops moving towards Buford’s 2,800 cavalrymen. Buford’s cavalry skirmished and retreated, holding back the Confederates and buying time until reinforcements could arrive. This sparring dance continued until Buford’s troops stopped atop McPherson Ridge, just as reinforcements from Maj. General John F. Reynolds’ I Corps arrived. Reynolds was killed in action later that morning in the brutal fighting around McPherson’s Ridge.

Upon hearing that Reynold’s had been killed, Meade sent in Maj. General Winfield Scott Hancock to take command.[6]John William Draper. History of the American Civil War (1870). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World. Hancock rallied the dispersed and retreating Union troops, who were badly outnumbered thanks to arriving Confederate reinforcements under Lt. Generals Richard Ewell and Ambrose Hill. But Hancock managed to consolidate his soldiers into strong defensive positions atop Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill.

Lee ordered Ewell to attack Cemetery Hill, but Ewell thought such an attack was unwise and did not. By nightfall, Meade himself had arrived in Gettysburg, and so too had Confederate Lt. General James Longstreet. Crucially for the Confederates, J.E.B. Stuart and his 10,000 cavalrymen still had not arrived in Gettysburg.[7]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government.

July 2, 1863: The Second Day

Both armies spent the night of July 1, 1863 moving their troops into position for a new day of fighting. Lee was still missing both Stuart’s cavalry and Maj. General George Pickett’s division. Meade’s army was in a strong defensive position atop Cemetery Hill, Culp’s Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and the two hills at the end of Cemetery Ridge, known as Big and Little Round Tops.

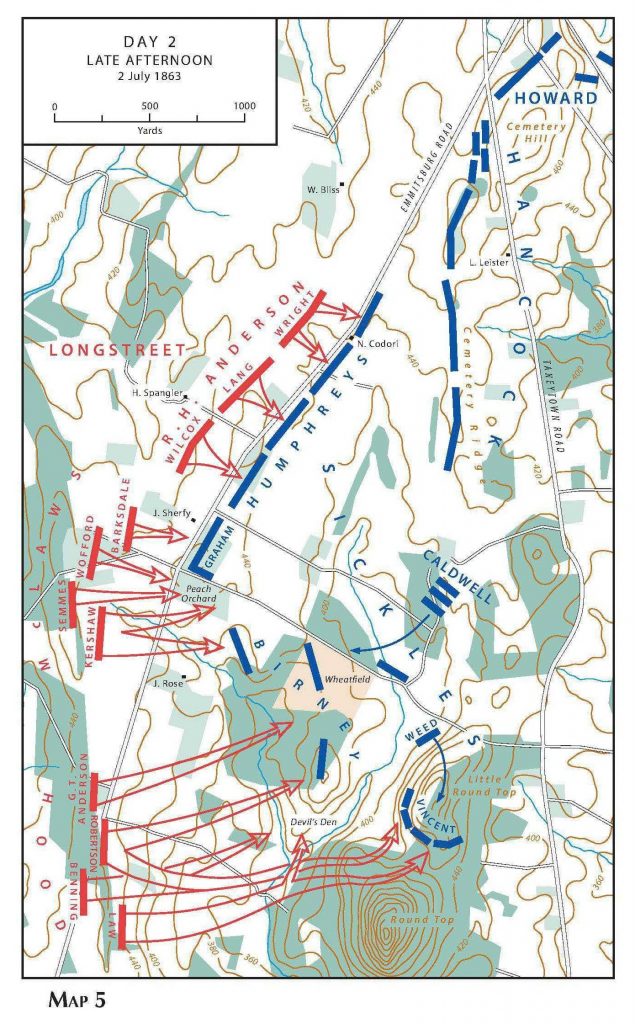

Lee ordered Longstreet to attack the left flank of the Union army at 11am, but Longstreet had strong reservations[8]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. about this strategy. Consequently, fighting that day did not start until almost 4pm, when additional divisions in Longstreet’s corps were finally moved into place. Despite the late start, the day would see some of the most notorious fighting of the entire war.

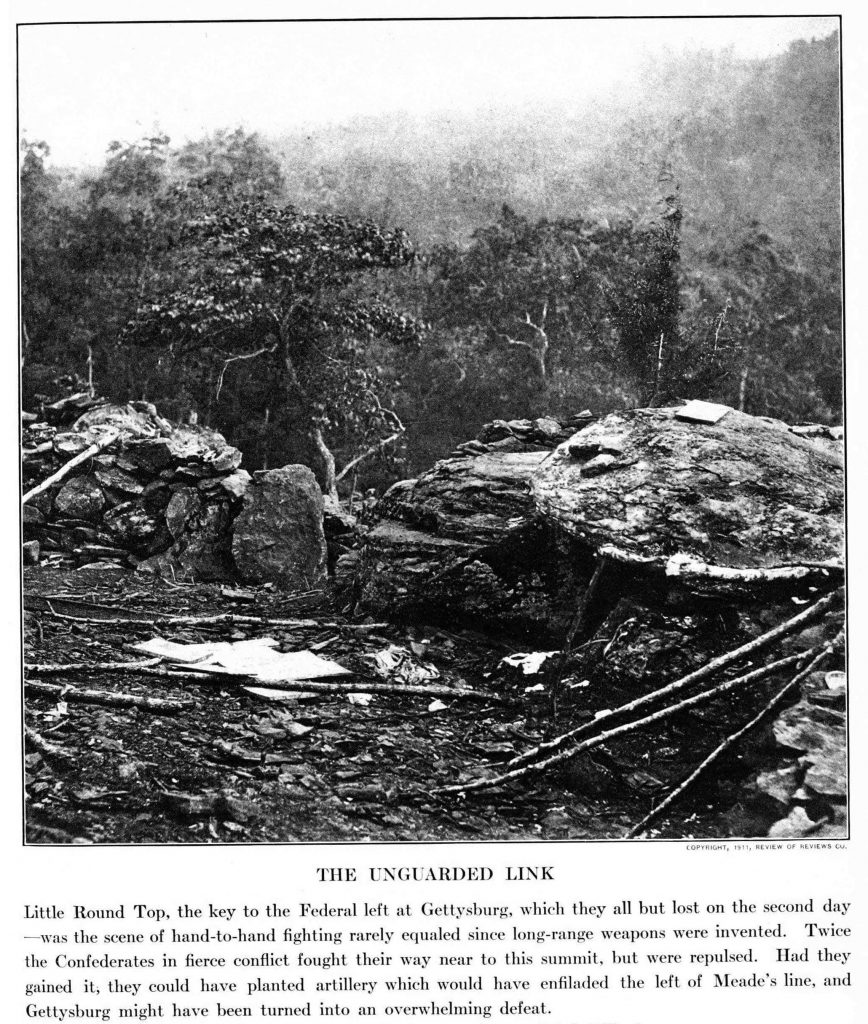

Little Round Top

Amidst the widespread fighting across Gettysburg, Confederate Maj. General Hood was assaulting the extreme left of Union Maj. General Daniel Sickles’ troops[9]Charles F. Horne. Great Events by Famous Historians: A Comprehensive and Readable Account of the World’s History, Emphasizing the More Important Events, and Presenting These as Complete Narratives in the Master-Words of the Most Eminent … Continue reading with artillery fire, pushing around to flank the Union line. His objective was to take unprotected Little Round Top. Little Round Top had been left undefended when Sickles moved his troops out of position from Meade’s original orders, leaving his troop line too thin to properly repulse any attack.

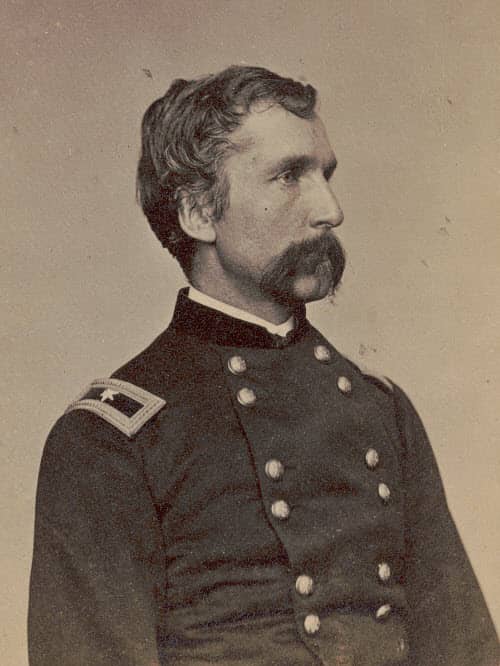

It was a potentially fatal mistake. If Little Round Top fell, the Confederates would have an open path to the Union line along Cemetery Ridge. Meade later said of Cemetery Ridge, “If the enemy had gained it, I could not have held my line.”[10]John William Draper. History of the American Civil War (1870). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World..}} Meade sent Brig. General Gouverneur K. Warren with a small signal detachment to defend Little Round Top.

Atop the hill, Warren could see what the Confederates were threatening to do, and redirected arriving reinforcements to occupy and defend the hill. Among the four Union regiments tasked with holdinging Little Round Top[11]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government.Military and Government.}} was the 20th Maine, led by Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Before the war, Chamberlain had been a professor at Bowdoin College. Now, Chamberlain and the 20th Maine were at the far left end of the Union line, staring down an approaching Alabama regiment.

The 20th Maine fought until they ran out of ammunition, and when they did Chamberlain ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge. Elsewhere on Little Round Top, the 44th New York was also engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat. At the far right of the Union flank, charging Confederates had nearly overpowered the 16th Michigan, when Brig. General Stephen Weed’s V Corps brigade arrived. Seeing the precariousness of their situation, Colonel Patrick O’Rorke immediately led his 140th New York in a daring charge. Many of his men had no time to load their rifles or fix bayonets,[12]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. using their rifles instead as clubs. Thanks to these valiant combined efforts, the Union held Little Round Top, but Colonel O’Rorke, General Weed, and one third of the 20th Maine were killed doing so.

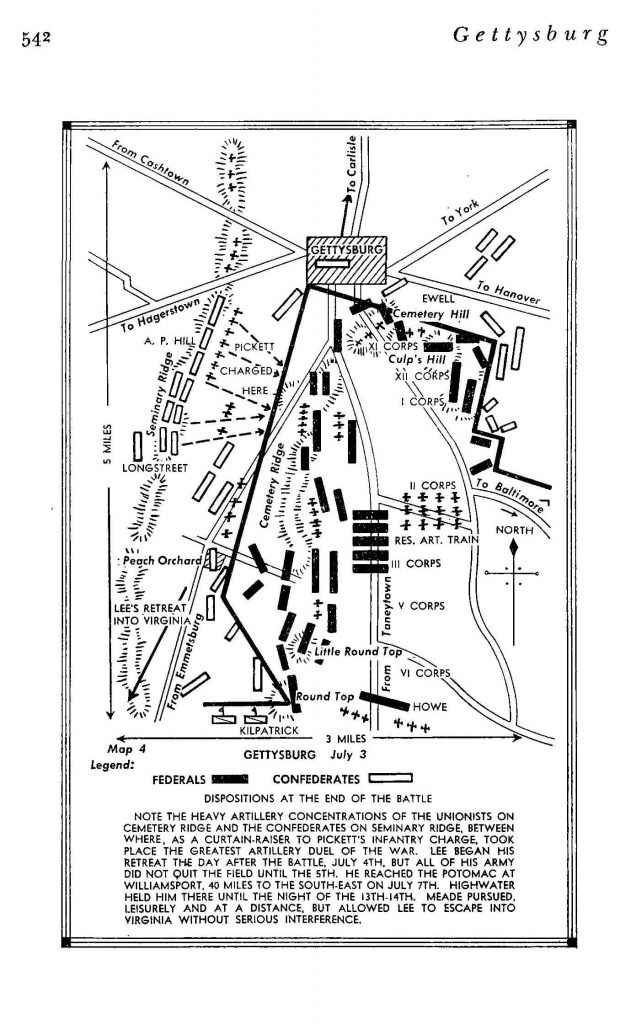

The Third Day: July 3, 1863

While Meade’s Army of the Potomac had averted disaster at Little Round Top, he had not escaped the day without strategic losses. The Peach Orchard had fallen to the Confederates, and Sickles himself lost a leg when he was hit by artillery fire in the Orchard. But the Union line held at Cemetery Ridge.

Lee’s plan for the final day of fighting was to attack the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Stuart’s cavalry had finally arrived, along with Maj. General George Pickett’s division. Lee’s plan called for three divisions—commanded by Generals Isaac Trimble, James Johnston Pettigrew, and George Pickett—to charge and break the Union center. Moving under the cover of artillery fire, they would drive the Union troops off the Ridge and out of Gettysburg. Again, Longstreet objected to his superior’s battleplan, and again his concerns were overruled.[13]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government.

Around 1pm on July 3rd, approximately 150 Confederate cannons[14]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. began their thunderous assault on the Union line. Some shot over their intended target, smashing apart supply wagons and even hitting Meade’s headquarters,[15]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. killing horses by the dozen. Eighty Union cannons fired back.[16]Charles F. Horne. Great Events by Famous Historians: A Comprehensive and Readable Account of the World’s History, Emphasizing the More Important Events, and Presenting These as Complete Narratives in the Master-Words of the Most Eminent … Continue reading The unceasing artillery fire continued for two hours until the Union cannons suddenly stopped firing. Lee believed their silence was evidence of their destruction; in reality, the Union troops were saving their ammunition[17]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. for the Confederate attack they knew had to be coming.

Pickett’s Charge

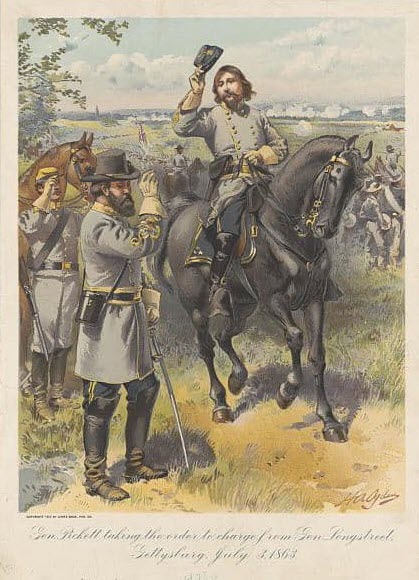

With the guns silent, Longstreet was now expected to order Trimble’s, Pettigrew’s, and Pickett’s divisions to charge across a mile of open ground to the Union line. Pickett’s division, made up of soldiers from Virginia, was to lead the charge. But Longstreet hesitated to give the order. Pickett asked Longstreet if he should advance. Longstreet simply nodded his head.[18]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. Longstreet told artillery commander General Edward Alexander, “I do not want to make this charge. I do not see how it can succeed. I would not make it now, but that General Lee has ordered it and is expecting it.”[19]Edward Shepherd; Murray Creasy, Robert Hammond, Editor. Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World (1943). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated.

15,000 Confederates began advancing towards Cemetery Ridge. As they marched, 100 Union cannons rained down shot and shell, tearing their ranks apart. Protected behind the ridge’s stone wall, Union soldiers fired off volley after volley of musket fire, shouting “Fredericksburg!” in reference to the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg,[20]John S. C. Abbott. History of the Civil War in America: Comprising a Full and Impartial Account of the Origin and Progress of the Rebellion, of the Various Naval and Military Engagements, of the Heroic Deeds Performed by Armies and Individuals, … Continue reading when it had been Union soldiers in an open field who were shot down by well-fortified Confederates. Many Confederates who managed to reach Cemetery Ridge realized the folly and futility of their position and simply surrendered.[21]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government.

After a futile hour, the Confederate troops retreated. Lee watched from Seminary Ridge and met the retreating men, telling them, “It was all my fault.”[22]Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. Still determined or deluded to succeed, Lee then ordered Pickett to rally his division for the counterattack. “I have no division,”[23]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. Pickett allegedly responded. He didn’t; sixty percent[24]Colin R. Ballard. Military Genius of Abraham Lincoln (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. of Pickett’s men were killed in the ill-conceived attack. Pettigrew’s brigade, who had also participated in the charge, had begun the battle of Gettysburg with 2,800 men; after the charge, only 835 were still alive.[25]John William Draper. History of the American Civil War (1870). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World.

Pickett’s Charge was last major assault of the battle of Gettysburg. The next day, July 4, Lee and his army retreated into Virginia. That same day, thousands of miles away, Vicksburg surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant, giving the Union control of the Mississippi River and cutting off valuable supply and trade routes for the Confederates.

Remembering Gettysburg

Gettysburg was the deadliest battle of the American Civil War. In three days of fighting,[26]Colin R. Ballard. Military Genius of Abraham Lincoln (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. the Union suffered 23,049 casualties; the Confederates are estimated to have endured a similar loss, with between 23,000–28,000 casualties, representing a loss of one third of Lee’s total army.[27]Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. For perspective, 58,220 Americans were killed over eight years of fighting in the Vietnam War.

The Gettysburg Address

On November 19, 1863, 15,000 people gathered in Gettysburg for the dedication of a new national cemetery. The star attraction at the dedication was former Massachusetts Governor, President of Harvard, and orator Edward Everett. Some two weeks before the event,[28]Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address – The True Story of Its Delivery, 31 Com. L. League J. 48 (1926). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. someone thought it might be nice to invite President Abraham Lincoln to deliver “a few appropriate remarks.”[29]Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics.

Everett spoke for over two hours at the dedication. When he was finished, President Lincoln gave his “few appropriate remarks,” reciting just 272 words. Today, of course, we know Lincoln’s words as the Gettysburg Address,[30]Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. one of the most famous speeches in all of American history—and arguably in the English language.

When Lincoln had finished speaking, Edward Everett approached him and said, “Ah, Mr. President, how gladly would I exchange all my hundred pages to have been the author of your twenty lines.”[31]Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address – The True Story of Its Delivery, 31 Com. L. League J. 48 (1926). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Lincoln, as indicated by the red arrow, at the Gettysburg National Cemetery dedication, where he delivered the Gettysburg Address. From the Library of Congress.

75th Reunion

The 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg took place in 1938. At the time of the reunion, it was estimated that there were approximately 14,000 Union and 9,000 Confederate veterans still living.[32]Establishment of commission in commemoration of 75th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg in 1938 (1936). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. The average age of these survivors was 93 years old.[33]Appropriation to aid in defraying expenses of observance of 75th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg (1938). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.

Perhaps recognizing the reality that the time for such reunions was passing, the federal government stepped in to make the 75th reunion possible, minting and selling a commemorative silver coin in 1936 to help raise funds.[34]49 Stat. 1524 (1919-1936) (1936). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. Congress extended an invitation[35]Appropriation to aid in defraying expenses of observance of 75th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg (1938). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. to every surviving veteran of the war and covered all their travel costs.[36]52 Stat. 354 (1938). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. President Roosevelt attended to dedicate the new Eternal Light Peace Memorial. Gettysburg’s 75th reunion would be the last battle anniversary to host Civil War veterans. Reporters captured the reunion, and you can view video footage of veterans at the reunion on YouTube.

Gettysburg Today

Private efforts to conserve Gettysburg’s battlefield began even before the war was over. In 1864, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association[37]James N. Gilbert, Crime in the National Parks: An Analysis of Actual and Perceived Crime within Gettysburg National Military Park, 12 Just. Prof. 471 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. was formed to preserve the battlefield and deter looters from cutting bullets from trees. In 1895, the Association transferred its lands to the federal government for its newly established national military park.[38]28 Stat. 651 (1885-1895) (1895). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. Today, the battlefield park is administered by the National Parks Service and an estimated 2 million people visit its hallowed ground every year.

Learn More with HeinOnline’s Military and Government

This post relied heavily on both modern and contemporaneous histories of the American Civil War, particularly the incredible ten-volume Photographic History of the Civil War. Looking for a one stop-shop that contains gems such as these? HeinOnline’s Military and Government database features more than 21,000 volumes and more than 3 million pages of content that tell the story of America’s fighting men and women.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Bradford A. Wineman. Chancellorsville Campaign, January-May 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑7, ↑11, ↑14, ↑17, ↑22 | Francis Trevelyan; Lanier, Robert S., Editors Miller. Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

| ↑3, ↑4, ↑5, ↑8, ↑12, ↑13, ↑15, ↑18, ↑21, ↑23, ↑27 | Carol Reardon and Tom Vossler. Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863 (2013). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

| ↑6, ↑10, ↑25 | John William Draper. History of the American Civil War (1870). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World. |

| ↑9, ↑16 | Charles F. Horne. Great Events by Famous Historians: A Comprehensive and Readable Account of the World’s History, Emphasizing the More Important Events, and Presenting These as Complete Narratives in the Master-Words of the Most Eminent Historians (1905). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑19 | Edward Shepherd; Murray Creasy, Robert Hammond, Editor. Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World (1943). This book is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑20 | John S. C. Abbott. History of the Civil War in America: Comprising a Full and Impartial Account of the Origin and Progress of the Rebellion, of the Various Naval and Military Engagements, of the Heroic Deeds Performed by Armies and Individuals, and of Touching Scenes in the Field, the Camp, the Hospital, and the Cabin (1866). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

| ↑24, ↑26 | Colin R. Ballard. Military Genius of Abraham Lincoln (1952). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

| ↑28, ↑31 | Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address – The True Story of Its Delivery, 31 Com. L. League J. 48 (1926). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑29, ↑30 | Glenn R. Capp. Famous Speeches in American History (1963). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑32 | Establishment of commission in commemoration of 75th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg in 1938 (1936). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑33, ↑35 | Appropriation to aid in defraying expenses of observance of 75th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg (1938). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑34 | 49 Stat. 1524 (1919-1936) (1936). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑36 | 52 Stat. 354 (1938). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑37 | James N. Gilbert, Crime in the National Parks: An Analysis of Actual and Perceived Crime within Gettysburg National Military Park, 12 Just. Prof. 471 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑38 | 28 Stat. 651 (1885-1895) (1895). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |