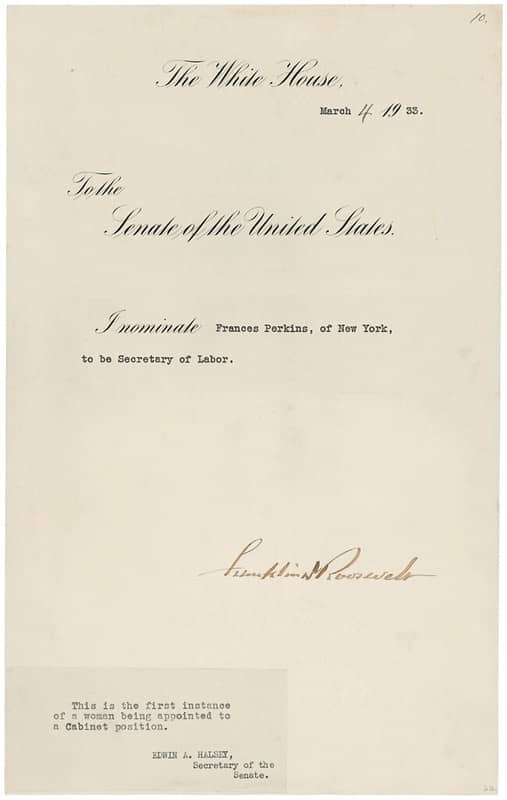

In honor of Women’s History Month, we are exploring the pioneering career of Frances Perkins, who became the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet when Franklin D. Roosevelt made her the fourth Secretary of Labor in 1933. Perkins’ remarkable career shaped the current social safety net and labor market that Americans live and work in today.

Early Life and Call to Service

Frances Perkins was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1880. She earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and physics from Mount Holyoke College[1]H.R. Rep. 96-665 (1979). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. in 1902. While attending Mount Holyoke, Perkins became involved in the women’s suffrage movement and took an American history class taught by Annah May Soule. As part of Soule’s class, Perkins and her fellow classmates were given an assignment where they had to tour a textile factory and paper mill to study their working conditions.[2]Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. It changed Perkins’ life.

After graduation, Perkins’ career shifted to social work. She moved to Chicago to work at the well-known Chicago Commons,[3]Jeanine Ferris Pirro, Reforming the Urban Workplace: The Legacy of Frances Perkins, 26 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 1423 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. a settlement house, where as part of her job duties she visited tenements and sweatshops. While in Chicago, Perkins lived at Hull House[4]Jane Addams. Twenty Years at Hull-House with Autobiographical Notes (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. and met its founders, Jane Addams[5]Jane Addams: A Centennial Reader (1960). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). and Ellen Gates Starr.

Perkins later moved to New York City to attend Columbia University and in 1910 she became the general secretary of the National Consumers’ League,[6]Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. which lobbied for safer industrial conditions. It was in New York City that Perkins’ life would once again change.

Frances Perkins in New York

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

On March 25, 1911, Frances Perkins was one of the many eyewitnesses[7]Virgilia Sapieha. Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.[8]Marcia L. McCormick, Consensus, Dissensus, and Enforcement: Legal Protection of Working Women from the Time of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire to Today, 14 N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y 645 (2011). This … Continue reading The factory employed predominately immigrant women and young girls who labored in sweatshop conditions. The fire started near closing time on the building’s 8th floor and quickly consumed the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors. Workers were unable to escape due to locked exit doors (to prevent unauthorized breaks) and broken, flimsy fire escapes. 146 workers died in the fire, mostly girls and young women between 16 and 23 years old.[9]Marcia L. McCormick, Consensus, Dissensus, and Enforcement: Legal Protection of Working Women from the Time of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire to Today, 14 N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y 645 (2011). This … Continue reading Many jumped to their deaths to escape the flames.

The New York State Factory Commission

In the fire’s deadly wake, New York State formed the New York State Factory Commission to review working conditions throughout the Empire State. Perkins worked as an investigator for the Commission. But she didn’t just write reports for the commissioners; she took them with her into the field[10]Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to see first-hand what workers dealt with on a daily basis and urged Albany to restrict women’s workweek to a “mere” 54 hours.[11]Virgilia Sapieha. Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy).

The New York State Factory Commission issued its final report, in thirteen volumes, in 1915. As a result of its work, the New York State legislature enacted 36 laws[12]Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. over the next two years that focused on safety, sanitation, workers’ compensation, and limiting working hours for women and children, at a time when such federal protections were non-existent. This legislation, borne from Perkins’ investigations, would later become the model for similar federal laws.[13]Jeanine Ferris Pirro, Reforming the Urban Workplace: The Legacy of Frances Perkins, 26 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 1423 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

In 1919, Perkins was appointed to the New York State Industrial Commission, which oversaw the state’s industrial code. She spent more than a decade working in state government, eventually becoming chairwoman of the New York State Industrial Board.[14]Virgilia Sapieha. Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). When Franklin D. Roosevelt became New York State Governor in 1929, he appointed Perkins as the New York State Industrial Commissioner. This working relationship with FDR would once again change Perkins’ life.

Frances Perkins in Washington, DC

FDR was elected president in 1933 and assumed responsibility over a country wrecked by the Great Depression. In 1933, nearly 13 million people were unemployed, almost 25% of the nation’s workforce. To help with the monumental task of repairing the country’s economy and getting Americans back to work. FDR nominated Perkins to be his Secretary of Labor. Perkins, however, had a condition for the president:[15]103 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 2 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. she would only join his cabinet if she had his support for major labor reforms, including unemployment relief, minimum wages, maximum work hours, child labor prohibitions, and the creation of a nationwide social safety net. Roosevelt agreed and Frances Perkins became the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet.

The first 100 days of Roosevelt’s administration were devoted to passing sweeping legislation to combat the Great Depression. Today, we know this group of laws as part of the New Deal. And because so much of the New Deal focused on relief for the unemployed and recovering the economy, Frances Perkins was in the midst of this legislative activity.

Most importantly, Perkins chaired the committee that drafted what would become the Social Security Act of 1935,[16]49 Stat. 620. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. which “helped remove the threat of starvation, eviction, and destitution from every worker’s doorstep”[17]103 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 2 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. by fundamentally changing America’s economic and social structure. After years of advocating for a minimum wage, maximum work hours, and the prohibition of child labor, these were finally achieved with the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act[18]52 Stat. 1060. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. in 1938.

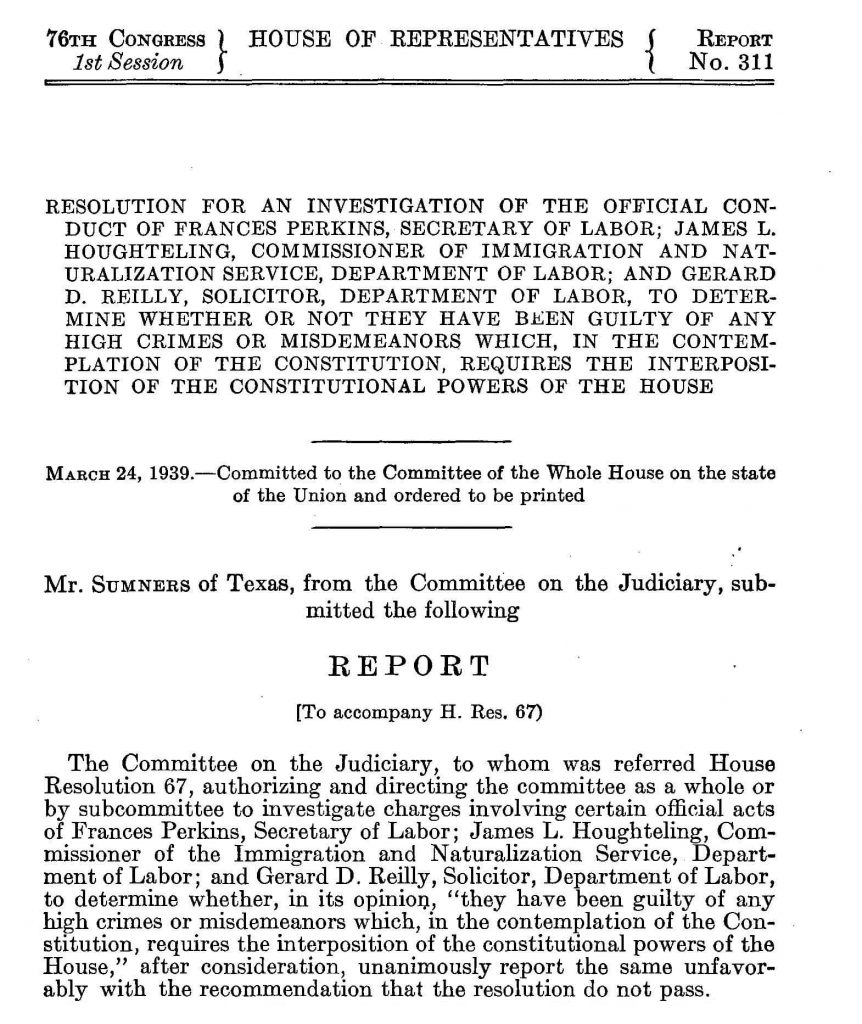

In 1939, an impeachment resolution[19]H. Rep. 79-311 (1939). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. was brought against Perkins by the House Un-American Activities Committee. At the time, the Bureau of Immigration was part of the Department of Labor. In 1937, Perkins refused to deport Harry Bridges, an Australian-born longshoreman, union leader, and suspected communist. The impeachment, and Bridges’ deportation, were ultimately unsuccessful.

Later Life and Legacy

Frances Perkins was the longest-serving Secretary of Labor, serving for 12 years. She resigned in 1945,[20]Harry S. Truman, Letter Accepting Resignation of Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor – May 23, 1945, 1945 Pub. Papers 63 (1945). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. shortly after Harry Truman assumed the presidency after FDR’s death. She remained in government, serving as a commissioner on the Civil Service Commission for seven years.[21]64 Ann. Rep. U.S. Civil Service Comm’n [i] (1946-1947). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Federal Agency Documents, Decisions, and Appeals. After leaving government, Perkins joined the faculty of Cornell University’s School of Industrial Labor Relations. She remained at Cornell until her death in 1965. Today, the Department of Labor headquarters is named the Frances Perkins Building.[22]1980 Pub. Paper 624 (1980). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library.

Every man and woman in America who works at a living wage, under safe conditions, for reasonable hours, or who is protected by unemployment insurance or social security is her debtor.

Keep Working with Labor and Employment: The American Worker

Interested in learning more about labor conditions in America? Our Labor and Employment: The American Worker collection is the perfect resource to learn about the rich history and current landscape of America’s workforce. In addition to books, reports, congressional documents, periodicals, and legislative histories, this collection also features a chart of landmark court cases that have shaped labor law in the United States, as well as an interactive timeline that features documents, photographs, and videos, a perfect resource for visual learners.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | H.R. Rep. 96-665 (1979). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑6 | Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | Jeanine Ferris Pirro, Reforming the Urban Workplace: The Legacy of Frances Perkins, 26 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 1423 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | Jane Addams. Twenty Years at Hull-House with Autobiographical Notes (1930). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑5 | Jane Addams: A Centennial Reader (1960). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). |

| ↑7, ↑14 | Virgilia Sapieha. Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). |

| ↑8, ↑9 | Marcia L. McCormick, Consensus, Dissensus, and Enforcement: Legal Protection of Working Women from the Time of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire to Today, 14 N.Y.U. J. Legis. & Pub. Pol’y 645 (2011). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑10, ↑12 | Gordon Berg, Frances Perkins and the Flowering of Economic and Social Policies, 112 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 28 (1989). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | Virgilia Sapieha. Eminent Women: Recipients of the National Achievement Award (1948). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Women and the Law (Peggy). |

| ↑13 | Jeanine Ferris Pirro, Reforming the Urban Workplace: The Legacy of Frances Perkins, 26 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 1423 (1999). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15, ↑17 | 103 MONTHLY LAB. REV. 2 (1980). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑16 | 49 Stat. 620. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑18 | 52 Stat. 1060. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑19 | H. Rep. 79-311 (1939). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑20 | Harry S. Truman, Letter Accepting Resignation of Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor – May 23, 1945, 1945 Pub. Papers 63 (1945). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑21 | 64 Ann. Rep. U.S. Civil Service Comm’n [i] (1946-1947). This report is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Federal Agency Documents, Decisions, and Appeals. |

| ↑22 | 1980 Pub. Paper 624 (1980). This paper is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |