On February 27, 1973, hundreds of Indigenous activists arrived in the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, site of the massacre in 1890, in which the US Army killed 300 people, mostly unarmed civilians. The occupation of the symbolically rich village sparked a two-month long siege where Indigenous activists from the Pine Ridge Reservation and the American Indian Movement confronted hundreds of armed federal agents.

The legacy of the siege at Wounded Knee is one of continued inspiration and controversy. The causes of the event are deeply intertwined with the history and politics of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, and with centuries of federal policy toward the Indigenous peoples of North America. Keep reading to learn more about the history of the siege of Wounded Knee, and the influence this event continues to have on present federal policy toward Indigenous nations.

A Note on Names and Terminology

Oceti Sakowin refers to the confederation of seven groups that make up the Indigenous nation often referred to as the Sioux. Many activists contend that the term “Sioux,” although commonly used in many popular and official contexts, is pejorative in origin. The Oglala Lakota are one of the seven sub groups that make up the Oceti Sakowin.

The American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement (AIM), much like the Black Panther Party, was founded in the inner city by young activists as a community defense organization. AIM, as it is commonly known, was founded by young Indigenous, primarily Ojibwe, activists in Minneapolis in 1968. Their initial actions were local, consisting of community patrols in which they observed police and reported on abuses.[1]Fay G. Cohen, The Indian Patrol in Minneapolis: Social Control and Social Change in an Urban Context, 7 LAW & SOC’y REV. 779 (1973). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Chapters were soon established in cities across the nation, and as AIM’s activism began to take on a more national character, activists began to stage more high-profile protests. In November 1972, activists seized and occupied the headquarters of the Bureau of Indian Affairs[2]Revolutionary Activities within the United States: The American Indian Movement (1976). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. in Washington, D.C., confiscating documents and reclaiming artifacts. In 1973, local activists among the Oglala Lakota in Pine Ridge called upon AIM for assistance[3]E. Ann Gill, An Analysis of the 1868 Oglala Sioux Treaty and the Wounded Knee Trial, 14 COLUM. J. TRANSNAT’l L. 119 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in the midst of a virtual civil war that was tearing their community apart.

Pine Ridge and the Wilson Regime

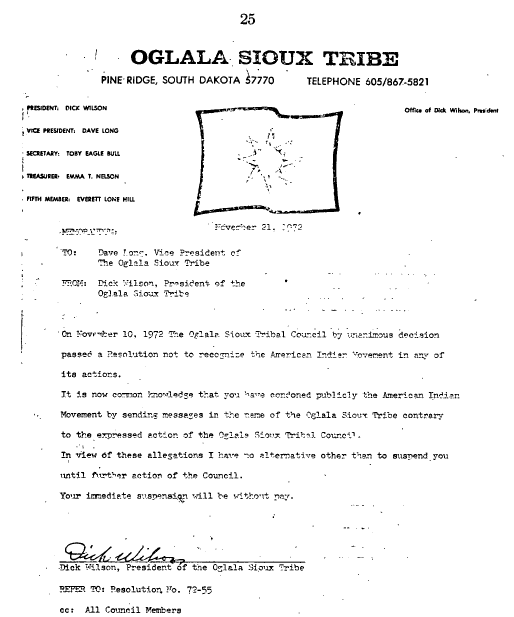

Tensions had been high on the Pine Ridge Reservation for months prior to the siege at Wounded Knee, in the aftermath of the election of Dick Wilson as tribal chairman of the Oglala Lakota of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Wilson, who allegedly came to power with the financial backing of white landowners surrounding the reservation, quickly gained a reputation for authoritarian rule. As tribal chairman, Wilson controlled the majority of paying jobs on the Pine Ridge Reservation. He purged the tribal government of any perceived supporters of AIM, even firing his own vice-president, and established a private militia, which he called the “Guardians of the Oglala Nation,”[4]Gregory K. Frizzell & Blaine G. Frizzell, Kent Frizzell: Lawyer, Public Servant, Law Professor 1929-2016, 53 TULSA L. REV. vii (2018). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. but most residents referred to as the “Goons.”

Wilson’s Goons supported the regime on the Pine Ridge Reservation with intimidation and violence. Outside the reservation, things were no safer for the Oglala Lakota. In the year prior to the siege at Wounded Knee, two tribal members—Raymond Yellow Thunder[5]5 AM. INDIAN L. NEWSL. [xiv] (1972). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. and Wesley Bad Heart Bull[6]E. Ann Gill, An Analysis of the 1868 Oglala Sioux Treaty and the Wounded Knee Trial, 14 COLUM. J. TRANSNAT’l L. 119 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.—were murdered by white men in towns just outside the borders of the reservation. In both cases, the defendants were charged with manslaughter, avoiding more serious murder charges, and released with no or very low bail.

By February 1973, conditions on the reservation had deteriorated to the extent that three members of the tribal council initiated proceedings to impeach Wilson and remove him from office. As E. Ann Gill, editor at the Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, wrote three years after the siege: “It was at this point that Wilson allegedly called for United States Marshal support on the reservation. Wilson managed to dominate his own impeachment hearings with the aid of a large federal force which had gathered on the reservation. As Gladys Bissonette, a member of the Sioux Civil Rights Organization on the reservation put it, “‘Dick Wilson acted as Chairman of the Tribal Council, and his own attorney, and his own prosecutor.’”[7]E. Ann Gill, An Analysis of the 1868 Oglala Sioux Treaty and the Wounded Knee Trial, 14 COLUM. J. TRANSNAT’l L. 119 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

The failed impeachment proceedings, followed soon thereafter by the murder of Wesley Bad Heart Bull, provided the impetus for the occupation of Wounded Knee. On February 27, a convoy of local activists and AIM members—many of whom were armed—entered the hamlet of Wounded Knee, site of the infamous massacre in 1890, and set up a protest camp.

Boarding Schools and Broken Treaties

Many of the participants in the actions at Wounded Knee cited grievances beyond those pertaining to Dick Wilson’s regime. In particular, leaders of the movement cited the United States’ violation of the terms of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie,[8]Sioux Indians: Treaty between the United States of America and different tribes of Sioux Indians, 15 Stat. 635 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties & Agreements Library. the second of two treaties of that name concluded between the Oceti Sakowin and representatives of the federal government.

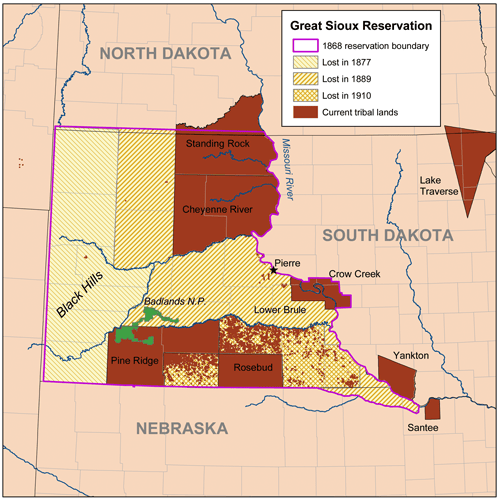

The second Treaty of Fort Laramie set aside a large reservation for the Oceti Sakowin—albeit one greatly reduced in size from that established by the first treaty in 1851[9]Charles J. Kappler. Indian Affairs Laws and Treaties (1904). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection.—including the Black Hills, which they hold to be sacred. The United States broke the terms of the treaty almost immediately; following the discovery of rich gold deposits in the Black Hills, the government dispatched a military expedition into the region in 1874, under the command of George Custer. This was followed by an influx of white settlers and miners. Over the course of the ensuing years, Congress made multiple modifications to the terms of the treaty, each time taking away more land from the initial reservation. By 1910, only a fraction of the land originally promised to the Oceti Sakowin remained.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie was hardly an anomaly. Quite the opposite—it was emblematic of all treaties signed between the United States and Indigenous nations in the 18th and 19th centuries, virtually all of which were violated.[10]Hannah Friedle, Treaties as a Tool for Native American Land Reparations, 21 NW. U. J. INT’l HUM. RTS. 239 (2023). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. In addition to the taking of Indigenous lands, the United States made a policy of eliminating Indigenous cultures by forcing the English language and European cultural and religious practices upon Indigenous nations. One of the primary vehicles for forced assimilation was the network of Indian residential schools that proliferated in the late 19th century.

The network of residential schools had their basis in the 1819 “Indian Civilization Act,”[11]Making provision for the civilization of the Indian tribes adjoining the frontier settlements., Chapter 85, 15 Congress, Public Law 15-85. 3 Stat. 516 (1819). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. which authorized the government to instruct Indigenous children in the “habits and arts of civilization.” Captain R.H. Pratt, of the United States Army, characterized this philosophy of education in much more brutal terms in 1892: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” From the late 19th century up until the 1970s, thousands of children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in residential schools, which were run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and a number of Christian missionary organizations. A similar, and longer-lasting, network of schools was established in Canada during this same time period.

The speaking of native languages and Indigenous religious and cultural practices were all forbidden in the school. Physical abuse and psychological torture was widespread and well documented.[12]Kimbirlee E. Sommer Miller, Truth and Reconciliation: Restorative Justice, Accountability, and Cultural Violence, 24 OR. REV. INT’l L. 195 (2023). Many of the elders on the Pine Ridge reservation, along with many leaders of AIM, were subjected to the residential school system. Their experiences there as children provided further impetus for their actions at Wounded Knee in 1973. This was a struggle not just for land, but for culture.

The Siege

Between 200 and 250 Oglala activists and AIM supporters set up camp in the village of Wounded Knee on February 27. Within a day, armed federal agents and militants from GOON had cut off all access to the town. Within a week, the village was surrounded by a thousand federal agents and troops, equipped with armored personnel carriers,[13]Kenneth E. Tilsen, U S Courts and Native Americans at Wounded Knee, 31 GUILD PRAC. 61 (1974). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. air support, and other heavy weaponry.

The siege would ultimately last more than two months, with life on the front lines falling into a curious pattern, with negotiations between the activists and federal forces alternating with periods of fierce fighting. Two Indigenous activists in the AIM camp, Frank Clearwater and Buddy Lamont, were killed in gunfights, and many more were wounded. Two federal agents were also wounded.

In the meantime, the confrontation was extensively covered in the media, and public opinion was moved in favor of the activists. AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Russel Means rose to fame as spokespeople for the activists, before the federal government—sensing the shift in public opinion—cut off media access to the camp 30 days into the siege.

After the death of Frank Clearwater in fierce fighting at the end of April, the Oglala leadership of the camp convened and resolved to end their occupation of the site. By May 5, they had reached an agreement to end the siege, and laid down their arms after more than two months.

The Aftermath

The end of the siege was followed by an intense crackdown on dissidents, with the federal government arresting more than 1,200 AIM activists[14]Zia Akhtar, Pine Ridge Deaths, Mistrials, and FBI Counter Plo Operations, 24 CRIM. JUST. STUD. 57 (2011). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and perceived supporters nationwide. Two of the most high-profile arrests were Russell Means and Dennis Banks, who had served as de facto spokespersons for AIM and the Oglala activists over the course of the occupation. In United States v. Banks,[15]United States v. Banks. 383 F. Supp. 368. This case can be found in FastCase. Banks and Means were tried on 10 counts each in federal court in Minneapolis. All charges against the two were dismissed on grounds of misconduct by the FBI over the course of its investigation, including perjury on the stand. In a scathing address, the federal judge overseeing the case referred to the government’s conduct as “sordid and misleading” and declared that the prosecution had “polluted the waters of justice.”[16]Ronald J. Bacigal, Judicial Reflections upon the 1973 Uprising at Wounded Knee, 2 J. CONTEMP. LEGAL ISSUES 1 (1988). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Of the more than 1,200 people arrested, only 15 would ultimately be convicted of any offense and, even then, the charges were mostly petty.[17]Zia Akhtar, Pine Ridge Deaths, Mistrials, and FBI Counter Plo Operations, 24 CRIM. JUST. STUD. 57 (2011). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

However, more than 50 AIM supporters and family members would die under suspicious circumstances[18]Zia Akhtar, Pine Ridge Deaths, Mistrials, and FBI Counter Plo Operations, 24 CRIM. JUST. STUD. 57 (2011). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.in Pine Ridge in the years following the siege, with homicide rates on the reservation climbing to a rate of 170 per 100,000, nearly 20 times the national average. Activists continue to allege FBI collusion with Wilson’s “goons” in the murders; the FBI disputes these facts and contends that the majority of deaths were accidental. The narrative of the siege and its aftermath remains fiercely contested at present.

On the national level, the years following the siege saw reforms to federal policy toward Indigenous nations. In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act,[19]To provide maximum Indian participation in the Government and education of the Indian people; to provide for the full participation of Indian tribes in programs and services conducted by the Federal Government for Indians and to encourage the … Continue reading which gave Indigenous nations greater control over the allocation and distribution of government funding. This increased the autonomy of Indigenous nations with respect to the federal government, and represented a departure from the policy of termination that had characterized the preceding decades, in which the federal government sought to decrease the power of tribes, and even eliminate them as governing bodies altogether.

Seven years after the siege, the Oceti Sakowin achieved a major victory in the United States Supreme Court in the case United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians,[20]United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians et al. , 448 U.S. 371, 437 (1980). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in which the Court ruled that tribal lands, including the sacred Black Hills, were illegally seized without compensation by the federal government. The Court awarded the Oceti Sakowin $17 million in compensation for the land seized in the 1870s, plus 100 years of interest, amounting to more than $100 million. However, the Black Hills were not returned, and the Oceti Sakowin declined the payment, on the grounds that accepting it would amount to relinquishing their land claims. The award has remained in trust, accumulating interest through the present day. Current estimates place its value at over $1 billion.

Further Research

To learn more about the history of Indigenous peoples in North America, and to stay up to date with the ever-changing relationship between Indigenous nations and state and federal governments, make sure you are subscribed to HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. The collection includes landmark cases and legislation, hearings, and a curated selection of scholarly articles updated monthly. One of its most useful features is the Treaty Search Tool, a searchable index of more than 400 treaties concluded between the United States government and dozens of Indigenous nations and tribes.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Fay G. Cohen, The Indian Patrol in Minneapolis: Social Control and Social Change in an Urban Context, 7 LAW & SOC’y REV. 779 (1973). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Revolutionary Activities within the United States: The American Indian Movement (1976). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. |

| ↑3 | E. Ann Gill, An Analysis of the 1868 Oglala Sioux Treaty and the Wounded Knee Trial, 14 COLUM. J. TRANSNAT’l L. 119 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | Gregory K. Frizzell & Blaine G. Frizzell, Kent Frizzell: Lawyer, Public Servant, Law Professor 1929-2016, 53 TULSA L. REV. vii (2018). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | 5 AM. INDIAN L. NEWSL. [xiv] (1972). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. |

| ↑6, ↑7 | E. Ann Gill, An Analysis of the 1868 Oglala Sioux Treaty and the Wounded Knee Trial, 14 COLUM. J. TRANSNAT’l L. 119 (1975). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Sioux Indians: Treaty between the United States of America and different tribes of Sioux Indians, 15 Stat. 635 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Treaties & Agreements Library. |

| ↑9 | Charles J. Kappler. Indian Affairs Laws and Treaties (1904). This document is available in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. |

| ↑10 | Hannah Friedle, Treaties as a Tool for Native American Land Reparations, 21 NW. U. J. INT’l HUM. RTS. 239 (2023). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | Making provision for the civilization of the Indian tribes adjoining the frontier settlements., Chapter 85, 15 Congress, Public Law 15-85. 3 Stat. 516 (1819). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑12 | Kimbirlee E. Sommer Miller, Truth and Reconciliation: Restorative Justice, Accountability, and Cultural Violence, 24 OR. REV. INT’l L. 195 (2023). |

| ↑13 | Kenneth E. Tilsen, U S Courts and Native Americans at Wounded Knee, 31 GUILD PRAC. 61 (1974). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14, ↑17, ↑18 | Zia Akhtar, Pine Ridge Deaths, Mistrials, and FBI Counter Plo Operations, 24 CRIM. JUST. STUD. 57 (2011). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15 | United States v. Banks. 383 F. Supp. 368. This case can be found in FastCase. |

| ↑16 | Ronald J. Bacigal, Judicial Reflections upon the 1973 Uprising at Wounded Knee, 2 J. CONTEMP. LEGAL ISSUES 1 (1988). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑19 | To provide maximum Indian participation in the Government and education of the Indian people; to provide for the full participation of Indian tribes in programs and services conducted by the Federal Government for Indians and to encourage the development of human resources of the Indian people; to establish a program of assistance to upgrade Indian education; to support the right of Indian citizens to control their own educational activities; and for other purposes., Public Law 93-638, 93 Congress. 88 Stat. 2203 (1975). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑20 | United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians et al. , 448 U.S. 371, 437 (1980). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |