In the 17th and 18th centuries, the vast overseas colonial empires of Britain, France, and Spain were connected to Europe by way of an expansive network of maritime trade routes. Transporting people and goods back and forth between the colonies and Europe was a lucrative business for the thousands of merchant mariners who sailed the seas. So too was piracy.

Piracy was also a dangerous business, and many pirates found themselves at the mercy of the English and colonial Courts of Admiralty. Keep reading as we use HeinOnline’s World Trials Library to explore the exploits and untimely ends of four infamous pirates.

William Kidd

William Kidd, better known as Captain Kidd, was one of the most famous men to be convicted of piracy. Born around 1654 in Scotland, the early details of Kidd’s life are somewhat murky and inconsistent. He became a sailor, and eventually a privateer, who was commissioned by England to defend British shipping in the Indian Ocean and to hunt and capture pirates and French vessels.

A privateer was essentially a licensed pirate. European nations of the time often hired armed private vessels to supplement their naval strength, and to attack enemy ships and disrupt the commerce of rival powers. Privateers were authorized by a letter of marque, a legal certificate that nations issued authorizing privateers to attach and seize the vessels of certain nations. Kidd and his crew often blurred the line between privateering and piracy, and seized a great many ships that fell outside the scope of their commission. Merchants complained to the powerful East India Company, which in turn complained to its allies in the Tory party in Parliament.

Ultimately, it was Kidd’s involvement in politics more so than piracy that proved to be his undoing. Kidd had powerful political patrons among the Whig party,[1]Joel Best, Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates, 9 DEVIANT BEHAV. 300 (1988). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. who had assisted him in obtaining his letter of marque, the document authorizing him to work as a privateer. In 1698, the leadership of the Whig government in London was in disarray, with the party on the verge of losing control of Parliament to their rivals, the Tories. Kidd’s Whig supporters had little political capital to expend in defending a notorious pirate, and their Tory rivals had a great deal to gain from associating the Whigs with Kidd.

The Tories got their opportunity in January 1698, when Kidd captured the Quedagh Merchant, an Armenian merchant vessel, captained by an Englishman. Kidd was already straining the legality of a commission, but this was a step too far. The Quedagh Merchant was carrying a valuable cargo of cotton, which belonged to an Indian nobleman with connections to the Mughal Empire, and political allies among the Tories in London. Kidd was classified as a pirate, and a warrant was issued for his arrest.

In July 1699, Kidd was arrested in New York City and imprisoned in Boston for two months before being shipped back to England for trial. Kidd maintained his innocence throughout the trial, but was ultimately found guilty of murder and piracy.[2]The Tryal of Captain William Kidd, for Murther and Piracy, upon Six Several Indictments. Compleat Collection of State-Tryals and Proceedings upon Impeachments for High Treason, and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours, from the Reign of King Henry the … Continue reading He was hanged on May 23, 1701, with his body publicly displayed in a hanging cage as a warning to others.

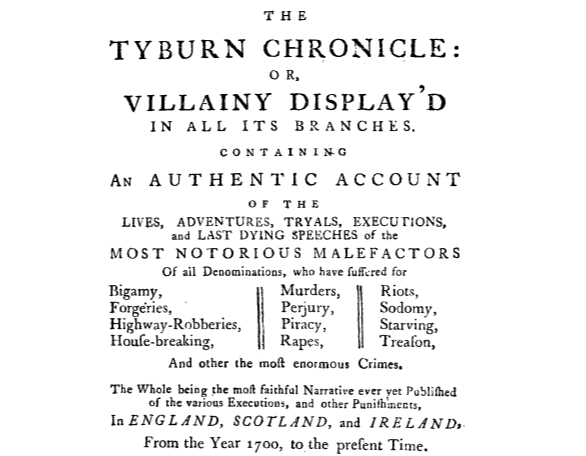

By the time of his execution, Kidd had already become something of a celebrity. After his execution, he became a sensation. Multiple pamphlets were published and circulated, and eagerly read by a fascinated public, each purporting to contain an authentic account of the “real” confession and last words[3]Graham Brooks (ed.). Trial of Captain Kidd (1930). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. of Captain Kidd. Salacious accounts of his exploits were published in the following decades, in somewhat lurid popular works such as Tyburn Chronicle: Or Villainy Display’d in All its Branches.[4] Account of Captain Kidd, his Piracies, Trial and Excecution. Tyburn Chronicle: Or, Villainy Display’d in All its Branches (1768). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. Interest in Captain Kidd was revived in the early twentieth century, with Kidd becoming a regular fixture in adventure fiction targeting young readers.

John Quelch

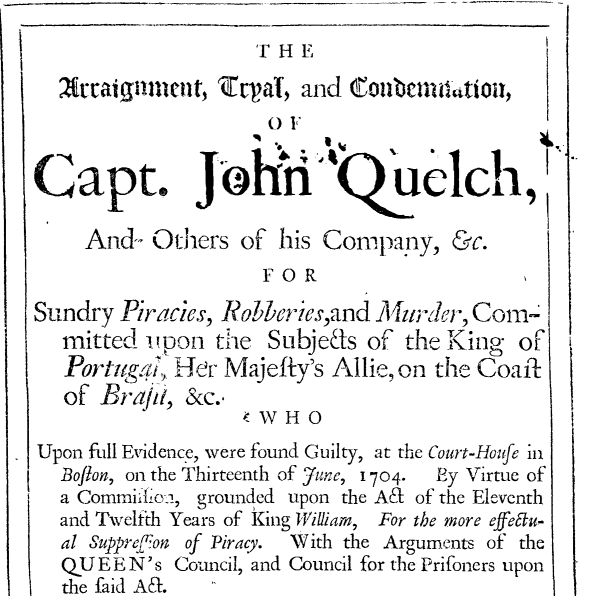

Unlike Kidd, whose conviction has been called into question, there is little doubt that John Quelch committed the crimes of which he was accused. Like Kidd, however, Quelch became caught up in political affairs that exceeded him. We know about John Quelch not so much for his deeds themselves, but because he was the first person to be tried for piracy without a jury in the Admiralty Courts,[5]Arraignment, Tryal, and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch, and Others of His Company, &c. for Sundry Piracies, Robberies, and Murder, Committed upon the Subjects of the King of Portugal, Her Majesty’s Allie, on the Coast of Brasil, … Continue reading which had been established in British colonies to address the growing number of piracy cases which were overwhelming existing civil and criminal courts. Quelch was unfortunate enough to be arrested shortly after the new law came into effect, making him a useful test case for the new system.

Quelch set sail from Boston in 1703 as a lieutenant on the Charles, under the command of Captain Daniel Plowman. The Charles was licensed as a privateer, and carried with it a letter of marque authorizing it to seize French and Spanish vessels (Britain was at war with the two empires at the time) off the coast of Newfoundland. The crew mutinied and threw Plowman overboard, electing Quelch as their new captain. They set course for the coast of Brazil, where they plundered a number of Portuguese ships. As Britain was not at war with Portugal at the time, this fell outside of the scope of their letter of marque. When the Charles arrived back in Boston, missing its captain and filled with Portuguese plunder, Quelch and his co-conspirators were promptly arrested and charged with piracy and murder.

Quelch’s arrest presented a wonderful career opportunity for Paul Dudley, the young Attorney General for the Province of Massachusetts Bay, who would be the first person in the British Empire to prosecute someone for piracy under new and stricter statutes of the recently passed “Act for the More Effectual Suppression of Piracy.”[6]House of Lords. The Manuscripts of the House of Lords, 1699 -1702; with an Appendix, the Journal of the Protectorate House of Lords, from the original Manuscript in the possession of Lady Tangye. (1908). This document can be found in … Continue reading Dudley delivered his opening statement with suitable intensity, claiming that Quelch “stands articled against, for, and charged with several piracies, robberies and murder…the worst and most intolerable crimes committed by men.”[7]Stephen C. O’Neill, The Forwardness of Her Majesty’s Service: Paul Dudley’s Prosecution of Pirate Captain John Quelch, 6 MASS. LEGAL HIST. 29 (2000). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading

Quelch was hanged in Boston on June 30, 1704. As he ascended the platform of the gallows, Quelch “pulled off his hat, and bowed to the spectators,” warning them to “take care how they brought money into New England, [lest they] be hanged for it.”[8]Arthur Merton Harris. Black Flag from Boston – John Quelch. Pirate Tales from the Law (1923). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library.

Thomas Green

Thomas Green was arrested for piracy in August 1704 in the port of Leith, Scotland. Much like Kidd, Green could be said to have met his doom thanks to politics more so than piracy. In fact, it is quite possible that poor Captain Green was not a pirate at all; he was an unlucky pawn in the rivalry between English and Scottish trading corporations.

In the Stair Society’s The Trial of Captain Green,[9]J. Irvine Smith, Trial of Captain Green, The, 62 Stair Society 217 (2015). This article can be found in Scottish Legal History: Featuring Publications of the Stair Society on HeinOnline. J.Smith Irvine suggests that Green’s trial was the result of what was essentially a case of insurance fraud on the part of the Company of Scotland, the monopoly that controlled overseas trade between Scotland and British colonies overseas. The Company had recently suffered costly losses in its overseas trade, and was looking for ways to recoup them. The arrival of the English trading vessel Worcester was a godsend for the Company. Its young captain, Thomas Green, an “unassertive figure with a weakness for alcohol and some indifference to his instruction,” had all the qualities of a useful patsy. The directors of the company drew up rather flimsy charges of piracy and murder against Green and members of his crew, empowering them to seize the Worcester and confiscate its cargo.

The manner of Green’s arrest was likewise unorthodox, with agents of the Company of Scotland posing as friendly revelers, plying the crew of the Worcester with “brandy, limes, sugar, and the prerequisites of an acceptable and hopefully powerful punch” and set about “lulling all the crew into full security with drinking, singing &c.”[10]J. Irvine Smith, Trial of Captain Green, The, 62 Stair Society 217 (2015). This article can be found in Scottish Legal History: Featuring Publications of the Stair Society on HeinOnline. When the crew of the Worcester were good and drunk, the disguised agents drew concealed weapons and took the crew prisoner and seized the vessel. Many historians contend that Green and his crew were most likely not guilty of the crime of which they were accused, although some hedge their bets and assert that Green was not guilty of the crimes for which he was convicted, but that he had committed different acts of piracy elsewhere.

Green was convicted of piracy and murder and sentenced to die by hanging,[11]Thomas Salmon, The Trial of Captain Thomas Green, and His Crew. Tryals for High-Treason, and Other Crimes. With Proceedings on Bills of Attainder, and Impeachments. For Three Hundred Years Past (1720). This document can be found in … Continue reading with a scheduled execution date of April 3, 1705. However, the case—in which a Scottish corporation and court sentenced an English captain and crew to death under suspicious circumstances—had served to inflame cross border tensions between Scotland and England at a politically sensitive time. The controversy reached the highest levels of government and, on March 25, Queen Anne interceded[12]William Roughead, Toll of the Speedy Return , 27 JURID. REV. 267 (1915). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to request a delay in the sentence. However, this reprieve was short-lived. Conscious of the ongoing negotiations between England and Scotland which would culminate[13]English text of the Union with Scotland Act 1706 as amended to 1993 (2010) This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated collection. in the Treaty and Acts of Union, which joined England and Scotland as one kingdom in 1707, the Queen withdrew her objection and Green and two of his crew were hanged on April 11, 1705.

Stede Bonnet

Stede Bonnet, occasionally known as “the Gentleman Pirate,” was an unusual pirate. Most pirates of the age started off, like Kidd and Quelch, as legally employed privateers whose extralegal indiscretions eventually led them to be labelled as full-on pirates. Bonnet wanted to become a pirate from the outset. Bonnet came from a wealthy English family in the colony of Barbados, and had a substantial fortune. Bonnet was bored with his life, unhappy in his marriage, and perhaps a little unwell.[14]Shirley Carter Hughson. Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce, 1670-1740 (1894). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Prestatehood Legal Materials collection. So, in 1717, he decided to become a pirate. Using his own money, he contracted with a shipyard to build him a sloop, which he armed, equipped and crewed.

Despite lack of seafaring experience, Bonnet set out as captain of his ship, which he named the Revenge. He had some success, and briefly associated with Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard. Seeking a veneer of legality, Bonnet briefly sought a letter of marque, which would have established his credentials as a privateer. These inquiries were unsuccessful, and he soon returned to piracy—reluctantly, some say. Bonnet was an eccentric and oddly unenthusiastic pirate. He is reported to have spent most of his time in his cabin, and seemed disinterested in the day-to-day workings of his crew. When he did appear above deck, he often did so in a stained nightshirt. His career proved to be a brief one.

In September 1718, two armed sloops dispatched by the colonial authorities in South Carolina caught up with Bonnet. After a brief but bloody battle[15]Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates, Who Were All Condemn’d for Piracy (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. off the Cape Fear River, Bonnet was arrested and brought to Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina) for a trial. Following a brief jailbreak by Bonnet and others, the trial commenced in a Court of Vice-Admiralty[16]Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates, Who Were All Condemn’d for Piracy (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. in October 1718, with multiple members of Bonnet’s crew testifying against him. In a curious defense strategy, Bonnet claimed to have no control[17]Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates, Who Were All Condemn’d for Piracy (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. over the actions of his crew, who he claimed had no respect or regard for his orders. Based on what we know of Bonnet from the historical record, this may very well have been true. It made no difference to the Judge of the Vice-Admiralty, who found Bonnet guilty of piracy, and sentenced him to death by hanging. In his sentencing speech, the judge, Nicholas Trott, added that Bonnet could look forward to the afterlife where he would be cast into “the Lake which burneth with Fire and Brimstone, which is the second Death.“[18]Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates, Who Were All Condemn’d for Piracy (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. Bonnet was hanged on December 10, 1718 in Charles Town, and buried in an unmarked grave.

HeinOnline’s World Trials Library

More trials of famous pirates and others can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library, which contains nearly 5,000 titles and 2 million pages of trial transcripts and other critical court documents, as well as trial-related resources such as monographs, which analyze and debate the decisions of famous trials. This database also includes biographies of many of the greatest trial lawyers in history and other previously hard-to-obtain historical content, as well as related scholarly articles hosted in various HeinOnline databases. If you or your institution have not yet subscribed to this collection, you can request a quote here. If you’re interested in further reading about pirates and maritime law, check out our blog for further reading.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Joel Best, Captain Kidd and the War against the Pirates, 9 DEVIANT BEHAV. 300 (1988). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Tryal of Captain William Kidd, for Murther and Piracy, upon Six Several Indictments. Compleat Collection of State-Tryals and Proceedings upon Impeachments for High Treason, and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours, from the Reign of King Henry the Fourth to the End of the Reign of Queen Anne (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑3 | Graham Brooks (ed.). Trial of Captain Kidd (1930). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑4 | Account of Captain Kidd, his Piracies, Trial and Excecution. Tyburn Chronicle: Or, Villainy Display’d in All its Branches (1768). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑5 | Arraignment, Tryal, and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch, and Others of His Company, &c. for Sundry Piracies, Robberies, and Murder, Committed upon the Subjects of the King of Portugal, Her Majesty’s Allie, on the Coast of Brasil, &c (1705). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑6 | House of Lords. The Manuscripts of the House of Lords, 1699 -1702; with an Appendix, the Journal of the Protectorate House of Lords, from the original Manuscript in the possession of Lady Tangye. (1908). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s UK Parliamentary & Government Publications (Public Information Online) collection. |

| ↑7 | Stephen C. O’Neill, The Forwardness of Her Majesty’s Service: Paul Dudley’s Prosecution of Pirate Captain John Quelch, 6 MASS. LEGAL HIST. 29 (2000). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8 | Arthur Merton Harris. Black Flag from Boston – John Quelch. Pirate Tales from the Law (1923). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑9, ↑10 | J. Irvine Smith, Trial of Captain Green, The, 62 Stair Society 217 (2015). This article can be found in Scottish Legal History: Featuring Publications of the Stair Society on HeinOnline. |

| ↑11 | Thomas Salmon, The Trial of Captain Thomas Green, and His Crew. Tryals for High-Treason, and Other Crimes. With Proceedings on Bills of Attainder, and Impeachments. For Three Hundred Years Past (1720). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑12 | William Roughead, Toll of the Speedy Return , 27 JURID. REV. 267 (1915). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13 | English text of the Union with Scotland Act 1706 as amended to 1993 (2010) This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated collection. |

| ↑14 | Shirley Carter Hughson. Carolina Pirates and Colonial Commerce, 1670-1740 (1894). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Prestatehood Legal Materials collection. |

| ↑15, ↑16, ↑17, ↑18 | Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates, Who Were All Condemn’d for Piracy (1719). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |