On April 28, 1967, in the midst of the United States’ escalating war in Vietnam, Muhammad Ali, the most famous boxer in the country, refused to be drafted into the United States Armed Forces. In a prepared statement, Ali explained “I have searched my conscience and I cannot be true to my belief in my religion by accepting such a call.” Ali was indicted and charged with violating the Selective Service Act,[1]To provide for the common defense by increasing the strength of the armed forces of the United States, including the reserve components thereof, and for other purposes., Public Law 80-759 / Chapter 625, 80 Congress. 62 Stat. 604 (1949) (1948). This … Continue reading and convicted. Ali would ultimately appeal his conviction all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Keep reading to learn more about the trials of Muhammad Ali, and the continuing influence of Clay v. United States.

Early Career and Conversion to Islam

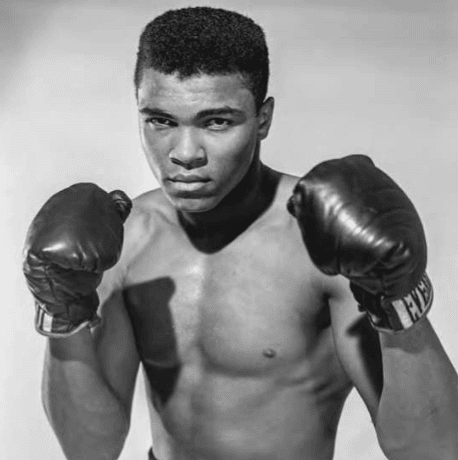

Muhammad Ali was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1942. He began training as an amateur boxer as a child, and first rose to fame when he won the gold medal for boxing in the light heavyweight division at the age of 18 at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. He made his professional debut later that year, with the first of 61 wins he would attain over the course of his career. It was around this time that Ali converted from Christianity to Islam. His fame was cemented in 1964 when he won the world heavyweight championship, defeating the heavily-favored Sonny Liston in two matches. That same year, Ali renounced his previous name—Cassius Marcellus Clay, Jr.—referring to it as his “slave name,”[2]Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading and adopted the name he would be known by for the rest of his life: Muhammad Ali.

This public announcement, along with Ali’s affiliation with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, drew the attention and ire of many powerful people, including the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover. The day after Ali’s announcement, Hoover ordered FBI agents to inquire about Ali’s draft status.[3]Joyce A. Hughes, Muhammad Ali: The Passport Issue, 42 N.C. CENT. L. REV. 167 (2020). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection.

Conscientious Objection

In 1966, Ali was notified that his draft status had been changed to 1-A—available for military service— by the selective service board in Louisville, Kentucky. At the time, the United States was involved in an escalating and increasingly destructive war in Vietnam, which was opposed by a growing anti-war movement in the United States. Upon being informed of the change in his draft status, Ali applied for conscientious objector status, which would have exempted him based on his religious convictions, informing the local draft board that “to bear arms or kill is against my religion.”[4]John G. Browning, Float Like a Butterfly, and Sting Like a Supreme Court Opinion: Muhammad Ali’s Draft Evasion Trial, 13 TSCHS J. 25 (Fall 2023). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection.

Ali continued to fight, winning matches as he submitted successive appeals, each of which was rejected. On Ali’s request, the case was moved to Texas, where he challenged the racial composition of the all-white local draft boards in Kentucky. This challenge was also rejected, for the final time, and Ali was ordered to report to the Armed Forces Induction Center in Houston, Texas on April 28, 1967. Ali informed reporters of his plan to refuse the draft the week before his scheduled induction date.

Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home to drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? I ain’t go not quarrel with them Viet Cong.“[5]Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading

Ali reported to the army induction center in Houston on his appointed date and refused, three times, to step forward when his name was called.

Clay v. United States

Only hours after refusing to be inducted into the army, Clay was stripped of his titles and banned from boxing. Ali was excoriated in the sports press, with an editorial in Sports Illustrated going so far as to refer to Islam as a “so-called religion.”[6]Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in … Continue reading

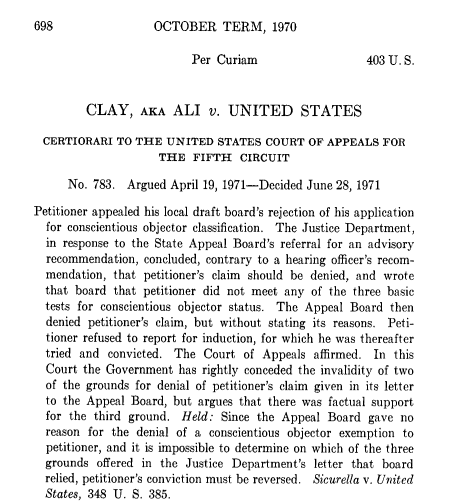

Ali’s trial before an all-white jury began in June 1967. Ali was convicted by the jury and was sentenced to the maximum penalty[7]John G. Browning, Float Like a Butterfly, and Sting Like a Supreme Court Opinion: Muhammad Ali’s Draft Evasion Trial, 13 TSCHS J. 25 (Fall 2023). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. of five years imprisonment and a $10,000 fine, a penalty far more severe than was typical for the offense. Ali and his legal team appealed his conviction to the Fifth Circuit. This appeal was rejected, on the grounds that the court asserted Ali as being opposed not to war in general, but to “only certain types of war, in certain circumstances, rather than a general scruple against participation in war in any form.”[8]Clay v. United States, 397 F.2d 901 (1968). This case is available in HeinOnline through Fastcase Premium.

Ali and his team appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which took the case. This was one of a number of cases in recent decades that centered on the question of conscientious objections to military service. In Sicurella v. United States[9]Sicurella v. United States, 348 U.S. 385, 396 (1955). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1955, the Court ruled in favor of a Jehovah’s Witness who filed for conscientious objector status in 1950, despite the petitioner’s avowed willingness to fight in “theocratic wars.” Furthermore, in an apparently positive development for Ali’s case, in 1970 the Court determined in Welsh v. United States[10]Welsh v. United States , 398 U.S. 333, 374 (1970). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. that non-religious objections to war were just as valid as religious objections for the purposes of attaining conscientious objector status.

However, this favorable ruling was mitigated somewhat by Gillette v. United States,[11]Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437, 475 (1971). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. a case decided on March 8, 1971, only a month before arguments began in Ali’s case before the Court. With Gillette, the Court added constraints to the criteria for conscientious objector status, by asserting that claimants must demonstrate opposition to all wars in principal, not only specific wars. This was the basis of the Fifth Circuit’s denial of Ali’s appeal.

Fortunately for Ali, the Court drew upon the precedent established in Sicurella and, in a per curiam ruling,[12]Clay, aka Ali v. United States, 403 U.S. 698, 710 (1971). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. it overturned Ali’s conviction after a great deal of internal debate[13]Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in … Continue reading amongst the Justices. With his conviction reversed, Ali was allowed to return to boxing, although without the titles which had been stripped from him.

Ali’s Legal Legacy

Three years after the Supreme Court’s ruling, and more than seven years after he was stripped of his title, Ali won back the world heavyweight title when he knocked out George Foreman in the famous “Rumble in the Jungle” match in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) on October 30, 1974. Ali would continue to box for seven more years, before fighting his final match and retiring in 1981. Over the course of 61 professional fights, he accumulated a record of 56 wins and 5 losses. His pioneering use of the rope-a-dope fighting technique remains influential in the sport of boxing to the present day.

In 1984, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which he developed as a result of sustained head trauma over the course of years in the ring. Ali dedicated the remaining years of his life to philanthropy and public service. He died on June 3, 2016, at the age of 74.

In addition to his legacy in the sport of boxing, Ali’s name lives on in legislation, through the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act,[14]S. Rept. 106-83 1 (1999-06-21), Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. This document is available in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment (BLASE) collection. which was signed into law in 2000. For more on the intersections between boxing and legislation, researchers may also want to look into the excellent legislative history, Congress and Boxing: A Legislative History, 1960-2003.[15]Edmund P. Edmonds; William H. Manz. Congress and Boxing: A Legislative History, 1960-2003 (2005). This document is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Federal Legislative History Library.

Further Research

If you’re interested in learning more about the intersections between sports, law, and culture, HeinOnline has two databases dedicated to these very topics. Our Hackney Publications collection features in-depth legal analysis of every aspect of the sports law industry from Hackney Publications, the nation’s leading publisher of sports law periodicals. Additionally, Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment (BLASE), our largest collection of sports law material, features hundreds of topic-coded cases, government documents, court decisions, and thousands of articles from more than fifty legal periodicals dedicated to sports law, including Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal and Marquette Sports Law Review.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | To provide for the common defense by increasing the strength of the armed forces of the United States, including the reserve components thereof, and for other purposes., Public Law 80-759 / Chapter 625, 80 Congress. 62 Stat. 604 (1949) (1948). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s United States Statutes at Large collection. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑5 | Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. |

| ↑3 | Joyce A. Hughes, Muhammad Ali: The Passport Issue, 42 N.C. CENT. L. REV. 167 (2020). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. |

| ↑4 | John G. Browning, Float Like a Butterfly, and Sting Like a Supreme Court Opinion: Muhammad Ali’s Draft Evasion Trial, 13 TSCHS J. 25 (Fall 2023). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. |

| ↑6, ↑13 | Jesse D. H. Snyder, The Legacy of Muhammad Ali 45 Years after Clay v. United States: Why a Case on Selective Service Still Matters, 16 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 34 (Fall 2016). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. |

| ↑7 | John G. Browning, Float Like a Butterfly, and Sting Like a Supreme Court Opinion: Muhammad Ali’s Draft Evasion Trial, 13 TSCHS J. 25 (Fall 2023). This article is available in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library collection. |

| ↑8 | Clay v. United States, 397 F.2d 901 (1968). This case is available in HeinOnline through Fastcase Premium. |

| ↑9 | Sicurella v. United States, 348 U.S. 385, 396 (1955). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑10 | Welsh v. United States , 398 U.S. 333, 374 (1970). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑11 | Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437, 475 (1971). This case can be found in HenOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑12 | Clay, aka Ali v. United States, 403 U.S. 698, 710 (1971). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑14 | S. Rept. 106-83 1 (1999-06-21), Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act. This document is available in HeinOnline’s Business and Legal Aspects of Sports and Entertainment (BLASE) collection. |

| ↑15 | Edmund P. Edmonds; William H. Manz. Congress and Boxing: A Legislative History, 1960-2003 (2005). This document is available in HeinOnline’s U.S. Federal Legislative History Library. |