Who is SUE? Not your sister, or your next-door neighbor, or even someone who has existed within the last 50 million years. No, this Sue is, or rather, was, a giant, fearsome creature.

SUE is the name given to the largest, best-preserved, most complete Tyrannosaurus rex fossil found to date. Over 90% recovered by bulk, her skeleton now looms 13 feet high and nearly 45 feet long, with a head that alone weighs more than 600 pounds. She currently resides on exhibit at the Field Museum in Chicago.

But it wasn’t always that way. In fact, SUE has quite a controversial legal history that has revolved around the question, SUE is whose?

Uncovering SUE in HeinOnline

With the help of HeinOnline, you can do some digging for SUE yourself without even leaving your desk—or risking federal charges. To supplement this blog post, you can find content related to SUE in various HeinOnline databases, including:

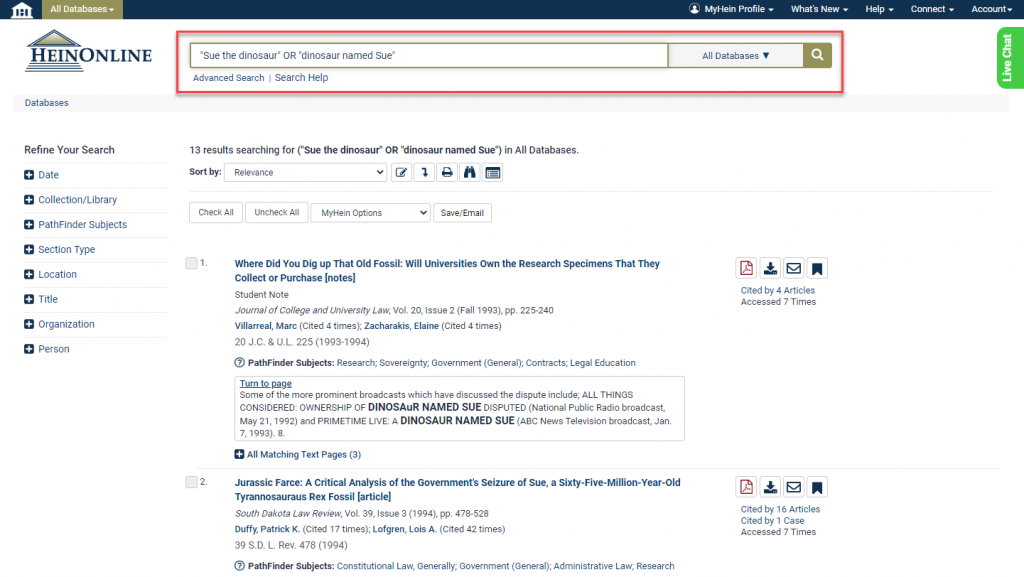

Looking for opinions and analyses about SUE and her contentious story? Head over to the Law Journal Library. In the search bar, type in a search such as “Sue the dinosaur” OR “dinosaur named Sue,” putting each phrase in quotation marks to search for the entire phrase and using all caps for the Boolean operator “OR.” You’ll find journal articles with various viewpoints, including titles such as:

- Jurassic Farce: A Critical Analysis of the Government’s Seizure of Sue, a Sixty-Five-Million-Year-Old Tyrannosaurus Rex Fossil[1]Patrick K. Duffy & Lois A. Lofgren, Jurassic Farce: A Critical Analysis of the Government’s Seizure of Sue, a Sixty-Five-Million-Year-Old Tyrannosaurus Rex Fossil, 39 S.D. L. REV. 478 (1994). This article is … Continue reading

- A Tyrannosaurus-Rex Aptly Named Sue: Using a Disputed Dinosaur to Teach Contract Defenses[2]Miriam A. Cherry, A Tyrannosaurus-Rex Aptly Named Sue: Using a Disputed Dinosaur to Teach Contract Defenses, 81 N.D. L. REV. 295 (2005). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

- Bones of Contention: The Regulation of Paleontological Resources on the Federal Public Lands[3]David J. Lazerwitz, Bones of Contention: The Regulation of Paleontological Resources on the Federal Public Lands, 69 IND. L.J. 601 (1994). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Them Bones

SUE was discovered thanks to a lucky accident. In the summer of 1990, the Black Hills Institute was searching for fossils on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The team was just about ready to head home when their truck broke down. While most of the team went to go find help, Sue Hendrickson stayed back, opting for a walk around the cliffs they hadn’t yet explored. That’s where she found what she suspected to be vertebrae. When the team returned, she told them the news, and led by BHI President Peter Larson, they proceeded to uncover an immense amount of fossilized bone. In total, it took six people and 17 days to extract all the existing pieces of SUE, named after the woman who first found the fossils.

BHI obtained permission from the owner of the property, a Cheyenne rancher named Maurice Williams, to remove the skeleton and paid him $5,000—which would turn out to be just a fraction of what the skeleton was actually worth. So, the Institute took SUE home and began to work on cleaning up the bones, until one day in 1992 when the FBI showed up at their doorstep.[4]Job Creation and Wage Enhancement Act of 1995 : hearings before the Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourth Congress, first session, on H.R. 9 (Title VI, VII, … Continue reading

The Cheyenne River Indian Investigation filed a complaint that the bones belonged to them since they were found on their reservation. And, the FBI had been watching the Black Hills Institute for a while for other charges of taking fossils from federal property as well as violations of the Antiquities Act of 1906,[5]To appropriate the sum of forty thousand dollars as a part contribution toward the erection of a monument at Provincetown, Massachusetts, in commemoration of the landing of the Pilgrims and the signing of the Mayflower compact., Public Law 59-210 / … Continue reading which protects historic or prehistoric artifacts on federally owned land. So, United States District Judge Richard Battey issued a search warrant. Larson and the Institute ended up with 158 charges—and SUE was taken away.

Suing for SUE

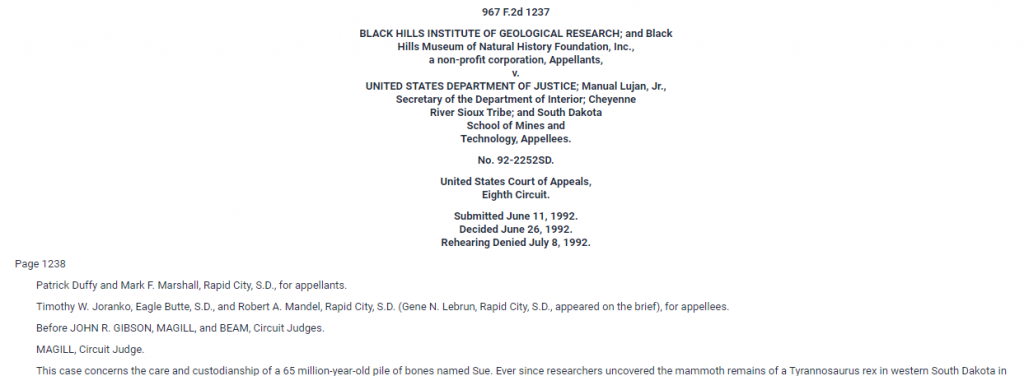

No one involved in this battle was going to go down without a fight. In 1992, in the case Black Hills Institute of Geological Research v. United States Department of Justice,[6]967 F.2d 1237 (8th Cir. 1992). This case is located in HeinOnline’s Fastcase database. the Black Hills Institute challenged the federal government for taking SUE—they had gotten permission to take the bones and even paid for them, although Maurice Williams believed that the $5,000 payment was solely for his consent for the Institute to dig on his property, not for the fossil itself. However, the court ultimately ruled that the seizure was justified.

In 1994, Peter Larson again fought for Black Hills Institute’s right to the bones.[7]In re Larson, 43 F.3d 410 (8th Cir. 1994). This case is located in HeinOnline’s Fastcase database. The court needed to consider who SUE actually belonged to. Did the BHI have the right to keep the bones, since they found them? Were they Williams’, since they were found on his property? Or did they belong to the Cheyenne tribe, since Williams’ property was on their reservation? Or, did the federal government have the right to keep the bones, since reservations are under federal jurisdiction? Judge Battey ultimately ruled against Larson—the bones belonged to the federal government.

SUE was given back to Maurice Williams, who would need to seek federal permission in order to sell the massive, fossilized dinosaur.

SUE Goes to Auction

Maurice requested the right to put SUE up for auction, and the federal government agreed. News about the Sotheby’s auction made quite a splash in the paleontology world. Several museums, including the Smithsonian, wanted to add SUE to their collections. However, with the financial help of private and public donors such as Walt Disney Parks and Resorts and McDonald’s, it was the Field Museum in Chicago that won SUE for a price higher than anyone had expected: a cool $8,362,500. And to this day, that is where this dinosaur resides, awing thousands of visitors per year.

Old Paleontology Laws Go Extinct

Naturally, the paleontology world was not a fan of all the drama surrounding SUE, and the fact that the T. rex could have ended up in the wrong hands. Several laws were introduced to help regulate fossil collecting, but they didn’t get very far. For example, in 1992, Senator Max Baucus of Montana introduced the Vertebrate Paleontological Resource Preservation Act (VPRPA)[8]David J. Lazerwitz, Bones of Contention: The Regulation of Paleontological Resources on the Federal Public Lands, 69 IND. L.J. 601 (1994). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in the hopes of creating a uniform federal policy for fossil collecting, banning it for commercial purposes. In 1996, South Dakota representative Tim Johnson introduced the Fossil Preservation Act (FPA).[9]142 Cong. Rec. H.B.1 (1996). This document is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. A 50-page CRS Report published in 2000 titled Assessment of Fossil Management on Federal and Indian Lands recommended new guidelines, with input from several agencies and the Secretary of the Interior.

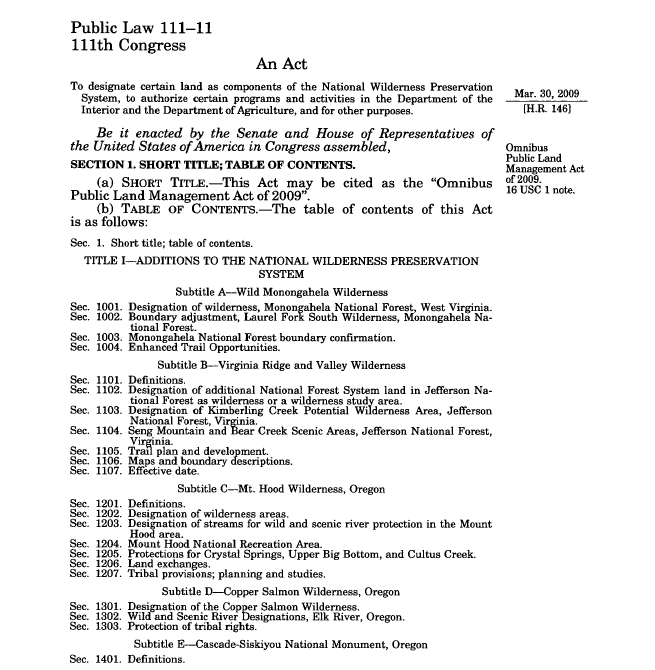

But it wasn’t until Barack Obama’s presidency that the Paleontological Resource Preservation Act (PRPA)[10]16 U.S.C. § 470 (2012) This act is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. was approved as part of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009.[11]Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-11, 123 Stat. 991 (2009). This act is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. This law limited public access to vertebrate fossils on land owned by the federal government by requiring diggers to request a permit from the Secretary of the Interior.

SUE Lives On

Today, SUE continues to call the Field Museum home. A few years ago, she was moved to a new permanent exhibit called Evolving Planet. However, SUE also has quite the active Twitter profile, where her pronouns are listed as “they/them” (no one knows what SUE’s biological sex was). SUE’s sense of humor certainly hasn’t gone extinct—as of this writing, the dinosaur’s account has 77.4K followers. And, of course, she remains in HeinOnline until another meteor comes to wipe us off the face of the Earth.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Patrick K. Duffy & Lois A. Lofgren, Jurassic Farce: A Critical Analysis of the Government’s Seizure of Sue, a Sixty-Five-Million-Year-Old Tyrannosaurus Rex Fossil, 39 S.D. L. REV. 478 (1994). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Miriam A. Cherry, A Tyrannosaurus-Rex Aptly Named Sue: Using a Disputed Dinosaur to Teach Contract Defenses, 81 N.D. L. REV. 295 (2005). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | David J. Lazerwitz, Bones of Contention: The Regulation of Paleontological Resources on the Federal Public Lands, 69 IND. L.J. 601 (1994). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | Job Creation and Wage Enhancement Act of 1995 : hearings before the Subcommittee on Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourth Congress, first session, on H.R. 9 (Title VI, VII, and VIII) … February 3 and 6, 1995, p. 162 (1995). This act is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑5 | To appropriate the sum of forty thousand dollars as a part contribution toward the erection of a monument at Provincetown, Massachusetts, in commemoration of the landing of the Pilgrims and the signing of the Mayflower compact., Public Law 59-210 / Chapter 3061, 59 Congress. 34 Stat. 225 (1906). This act is located in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑6 | 967 F.2d 1237 (8th Cir. 1992). This case is located in HeinOnline’s Fastcase database. |

| ↑7 | In re Larson, 43 F.3d 410 (8th Cir. 1994). This case is located in HeinOnline’s Fastcase database. |

| ↑8 | David J. Lazerwitz, Bones of Contention: The Regulation of Paleontological Resources on the Federal Public Lands, 69 IND. L.J. 601 (1994). This article is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9 | 142 Cong. Rec. H.B.1 (1996). This document is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑10 | 16 U.S.C. § 470 (2012) This act is located within HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. |

| ↑11 | Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 111-11, 123 Stat. 991 (2009). This act is located within HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |