During the mid-20th century, nuclear power was one of the fastest growing areas of science and technology. What could be better than creating sustainable nuclear energy? It was the largest source of clean power in America, it created tons of jobs, and developing nuclear power provided a solid sense of national security. Nuclear reactors were popping up across the nation to fuel our nation’s homes, businesses, and military. However, a lot of that excitement took a turn in 1979, when a partial nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island near Harrisburg, PA put the health and safety of employees and nearby civilians at risk. In this month’s edition of Secrets of the Serial Set, we’ll utilize the boundless resources within the U.S. Congressional Serial Set (now available in full in HeinOnline!), and our Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database, to explore what caused the Three Mile Island Disaster, as well as its many consequences.

A Morning Meltdown

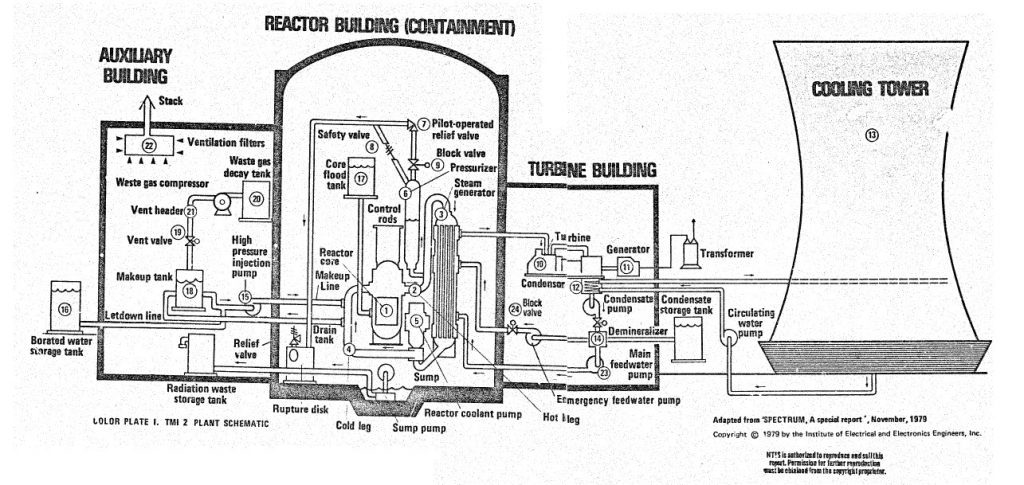

Early in the morning on March 28, 1979,[1]“Department of Energy civilian programs 1981 authorization act. 4 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. 1-4. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20932&i=276. This document can be … Continue reading the citizens of Londonderry Township along the Susquehanna River lay peacefully asleep, blissfully unaware that a catastrophe was brewing at the nearby Three Mile Island nuclear power plant within its TMI-2 unit. Around 4:00 a.m., some unknown failure caused the main feedwater pumps to stop sending water to the steam generators that help release heat from the reactor core. The reactor automatically shut down, as it was supposed to. The pressure in the unit’s primary system began to rise, so a pilot-operated relief valve[2]Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commissioners and to the Public (1980). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database. opened to drain the pressure. However, the valve was supposed to automatically close when safe pressure levels were restored—and it never did. Plant operators on duty did not notice because for some reason, control instruments indicated that the valve was closed. Meanwhile, steam was leaking out of the valve, and the unit’s reactor core overfilled with cooling water. As a result, employees turned off the reactor coolant pumps, still unaware that the relief valve was ajar, which caused the water level in the pressure vessel to drop and the core to overheat. In fact, the core got to 4,000 degrees….just 1,000 degrees short of a total meltdown.

The Realization

Radioactive gases began to leak into the nuclear plant. Alarms and warning lights went off. At 6:56 a.m., a plant supervisor called a site area emergency. Less than 30 minutes later, the station manager declared a general emergency.[4]Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commissioners and to the Public (1980). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database. The plant’s parent company, Metropolitan Edison, notified the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency, who in turn notified agencies across the state, as well as the governor and lieutenant governor. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission sent staff members to investigate the situation. In all of the ensuing chaos, mixed reports were given to agencies and the public—there was no consensus as to how severe the situation was or if the public was in danger. Metropolitan Edison claimed that there was no radiation detected off of plant grounds, but inspectors determined otherwise. However, over the course of the day, the situation was seemingly neutralized. At 8 p.m., the plant began to restart the pumps—but more than half of the reactor core was destroyed.[5]“Appropriations for Department of Energy, fiscal 1982, pt. I.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-30. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20715&i=80. This document can be found in … Continue reading

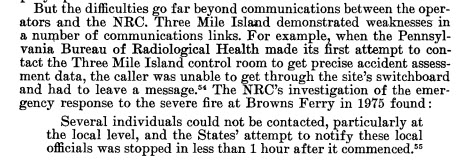

The lack of consensus as to the severity of the situation[6]“Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, … Continue reading resulted in conflicting evacuation recommendations. Lieutenant Governor William Scranton III initially told the public that there was nothing to worry about, but later said that the situation was more complex than he previously thought. He encouraged residents near the plant to stay indoors[7]“Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, … Continue reading and for schools to close. Additionally, Governor Dick Thornburgh recommended that pregnant women and young children within a five-mile radius of the facility temporarily evacuate. That radius was soon increased to 20 miles. Thousands of residents evacuated the area.

Beware of the Bubble

Two days later, on March 31, plant operators discovered that a bubble of highly flammable hydrogen gas[8]Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commissioners and to the Public (1980). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database. had formed within the TMI-2 unit’s pressure vessel as a result of the exposed core reacting with hot steam. Luckily, no oxygen was present within the vessel, which helped to prevent any fire or explosion. However, no one knew initially whether or not there was a presence of oxygen. On April 1, President Jimmy Carter, a trained nuclear engineer, came to Londonderry Township to inspect the plant. It was eventually determined that the hydrogen bubble was not going to explode, and it was gradually released into the atmosphere.

Overall, the Three Mile Island disaster was the worst American commercial nuclear power plant accident in history.

The Clean-up

Full clean-up of Three Mile Island took more than 14 years—from August 1979 to December 1993. The efforts in total cost about $1 billion. Almost 100 short tons of radioactive fuel were removed from the site.[9]“Appropriations to Nuclear Regulatory Commission.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-32. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20964&i=1185. This document can be found in … Continue reading The United States Environmental Protection Agency began daily sampling of the nearby area, but they determined that not enough radioactive material was released to threaten public health, and they found no contamination in local water, soil, or plants. Some of the workers in the plant had been exposed to dangerous radiation levels,[10]“Nuclear Regulatory Commission authorizations, 2 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-64. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20713&i=797. This document can be found in … Continue reading but the public was only exposed to about 1.7 millirem, which is approximately the amount that people living in larger cities are exposed to over the course of a week.

By 1988, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced that all remaining radioactivity was contained.

The Impact on the Nuclear Industry

Despite the fact that the aftermath of the partial meltdown wasn’t as severe as it could have been, it eroded public trust in nuclear energy. Anti-nuclear protests popped up around the world, including in America—in New York City, 200,000 people (including Jane Fonda) protested against nuclear power in September 1979.

Jimmy Carter created the President’s Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island in April 1979. Federal safety and design requirements for nuclear power plants became much stricter—the government passed the Nuclear Safety Research and Development Act of 1980,[11]“Nuclear safety research and development act of.1980.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. 1-10. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20897&i=625. This document can be found in … Continue reading as well as several amendments related to the disaster[12]“Nuclear Regulatory Commission authorizations.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-48. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20831&i=487. This document can be found in … Continue reading—and set forth plans to improve responses from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission,[13]“Reorganization plan no. 1 of 1980.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. I-8. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20908&i=15. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. … Continue reading which came under fire for not having proper emergency plans set in place.[14]“Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, … Continue reading And from 1980 to 1998, the number of nuclear reactors built sharply decreased. The decline of the nuclear power industry would be further accelerated by the Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine in 1986.

In 1981, citizens’ groups successfully filed a class action suit against Three Mile Island[15]557 F. Supp. 96 (1982) In Re Three Mile Island Litigation. This case can be found in Fastcase. and won $25 million in a settlement. Metropolitan Edison plead guilty in a plea deal after being indicted on criminal charges for falsifying safety test results before the accident. However, state courts rejected a class action lawsuit that stated that the disaster impacted public health.

Last year, Netflix released a four-part docuseries on this disaster, titled Meltdown: Three Mile Island.

Continue Your Research by Diving into the Serial Set

The U.S. Congressional Serial Set database is provided at no additional cost to all Core+ subscribers. We welcome you to explore this uniquely designed database to unearth all of the hidden stories within U.S. history—you never know what you might discover.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | “Department of Energy civilian programs 1981 authorization act. 4 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. 1-4. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20932&i=276. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3, ↑8 | Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commissioners and to the Public (1980). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database. |

| ↑4 | Three Mile Island: A Report to the Commissioners and to the Public (1980). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Reports of U.S. Presidential Commissions and other Advisory Bodies database. |

| ↑5 | “Appropriations for Department of Energy, fiscal 1982, pt. I.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-30. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20715&i=80. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑6 | “Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20869&i=1342. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑7 | “Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20869&i=1317. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑9 | “Appropriations to Nuclear Regulatory Commission.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-32. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20964&i=1185. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑10 | “Nuclear Regulatory Commission authorizations, 2 pts.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1981, pp. 1-64. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20713&i=797. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑11 | “Nuclear safety research and development act of.1980.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. 1-10. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20897&i=625. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑12 | “Nuclear Regulatory Commission authorizations.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-48. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20831&i=487. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑13 | “Reorganization plan no. 1 of 1980.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1980, pp. I-8. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20908&i=15. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑14 | “Emergency planning around U.S. nuclear powerplants, Nuclear Regulatory Commission oversight.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1979, pp. I-106. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset20869&i=1307. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set database. |

| ↑15 | 557 F. Supp. 96 (1982) In Re Three Mile Island Litigation. This case can be found in Fastcase. |