Fall’s arrival brings a chill to the air, changing colors to the leaves, and pumpkin spice flavoring to more products than necessary. But for many people, fall’s arrival also brings on an acute case of buck fever, alleviated only by long hours in a tree stand, or for others the urge to sit near the water in a duck blind with a bird call in hand, waiting for a fast-flying fowl. For these outdoorsmen and women, the change in weather means the start of the much-anticipated fall hunting season.

Hunting in America is primarily regulated at the state level, with additional regulations coming from federal laws that protect endangered species and migratory birds. In New York, for example, hunting is only permitted by license during defined seasons. These seasons determine what animals may be hunted during specific weeks of the year and the type of weapons that can be used to hunt them. For example, deer hunting in New York State has different seasons depending on the part of a state a hunter is in, whether he is hunting antlered or antlerless deer, and whether the hunter is using a bow, crossbow, muzzleloader, or shotgun, with additional restrictions implemented in specific areas of the state, such as the Catskills’ antler point restriction to prevent hunters from taking immature bucks.

New York State also has tag rules that require hunters to report to the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) any deer, turkey, or bear they harvest, allowing the DEC to implement quotas. Upon killing a deer, turkey, or bear, hunters must fill out one of the tags issued with their hunting license and report the kill to the DEC, providing information such as their hunter’s license number, location and date of the kill, and the sex of the animal; some animals require additional information to be reported and even part of the animal sent to the DEC, such as a tooth from a bear to determine the animal’s age. A hunter is only considered to be in legal possession of his kill once a carcass tag has been properly filled out and affixed to the animal.

Using HeinOnline, let’s point and flush out some of the laws that both regulate and preserve a hunter’s wild heritage in the United States and the history behind this ancient tradition. Follow the trail through these databases:

- Law Journal Library

- Legal Classics

- Selden Society Publications and the History of Early English Law

- U.S. Congressional Documents

- U.S. Congressional Serial Set

- U.S. Presidential Library

- U.S. Statutes at Large

A Royal’s Forest Grows

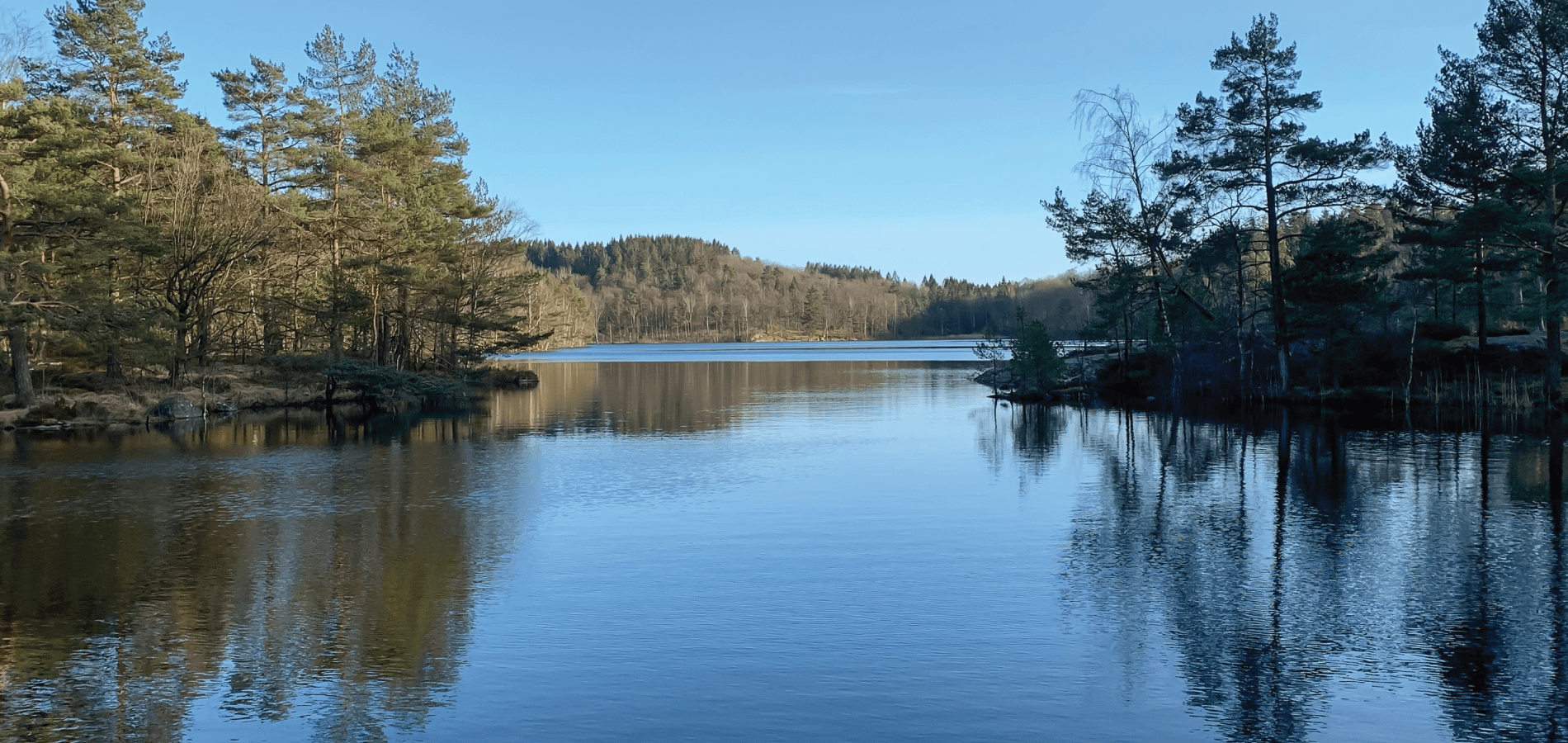

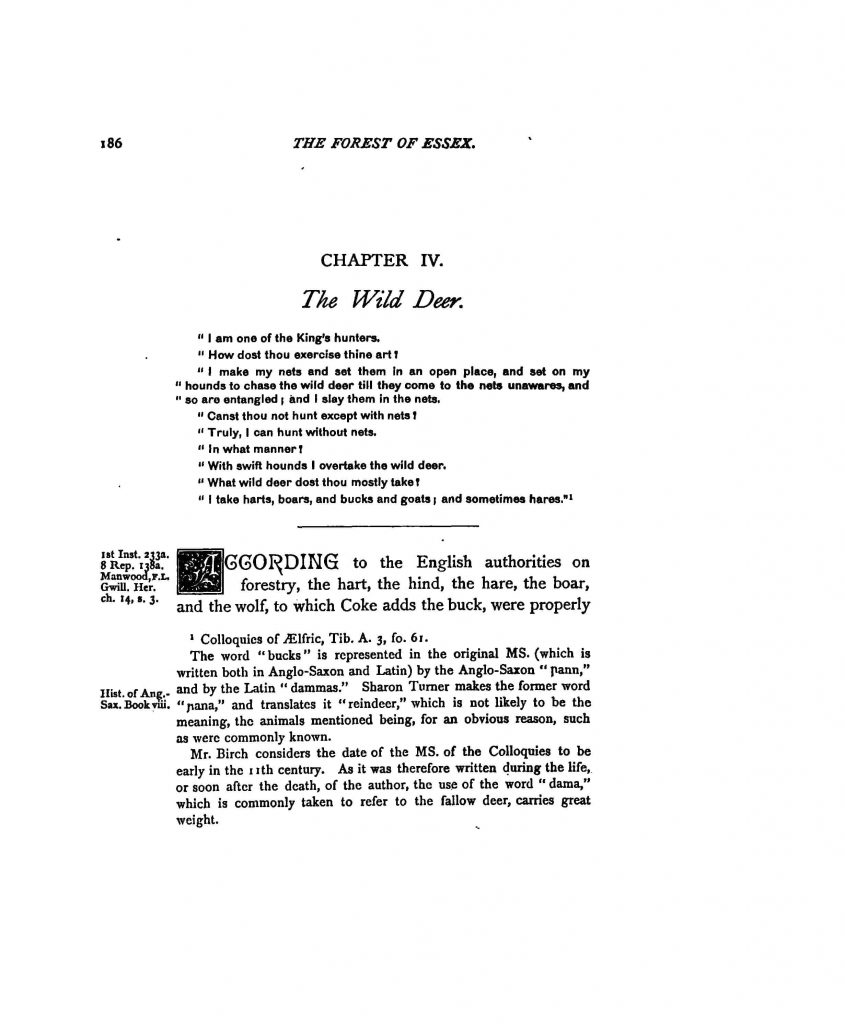

While one may be tempted to think that laws on hunting are a modern invention, in some societies regulations or restrictions on hunting have in fact existed for centuries. Perhaps the most well-known example is the ancient royal forests of England. William the Conqueror established a system of forest law after ascending the English throne in 1066. In William’s time, the word forest did not mean an area of wooded land such as we think of today, but was instead closer to our modern definition of a preserve. A royal forest, therefore, could include all types of land, such as woodland, heaths, moors, and marshland. A lover of hunting, William’s royal forests and the forest law that governed them preserved the venison—beasts who lived on the land, including boar and rabbits, but the red deer above all—and the vert that sustained them—the grassland, water, woodland, and so on—for the exclusive privilege of the sovereign and his invited guests to hunt upon.

The forests placed under protection by William and his successors were massive, with entire towns and villages falling within their boundaries; by 1189, between one quarter and one third of England fell within the boundaries of the royal forest, including the entire county of Essex. These lands fell outside the jurisdiction of common law and instead were governed by forest law. Forest law was enforced by a complicated network of wardens, bailiwicks, rangers, verderers—who investigated crimes and recorded offenses—and the forest eyre, the magistrate who presided over cases concerning the various forests.

Because use of the royal forest was restricted, poaching was taken seriously, with verderers gathering around the dead animal and calling witnesses in a proceeding that looks similar to a modern coroner’s inquest. Poaching and trespassing carried the vicious penalty of mutilation or even death. But being denied the right to kill a king’s deer, or even fish in the king’s streams or snare a royal rabbit, was not the only issue that stoked animus between the sovereign and his subjects. Because forest law also protected the vert, the physical land of the forest, and because the royal forests were so extensive, huge swaths of land could not be used by the common man to provide timber, peat, or charcoal, invaluable fuel for heating and cooking in medieval England. Good arable land also could not be cultivated for farming or used for grazing, imposing real hardship on the people who relied on the land to survive.

The Charter of the Forest sought to redress these complaints. Sealed by King Henry III in 1217, the Charter re-established rights of access to the royal forest for free men, allowing them to use the land for grazing, and repealed both mutilation and the death penalty for poaching. Portions of the Charter remained in effect until 1971, when it was superseded by the Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Act.

Americans Conserve Her Wild Treasures

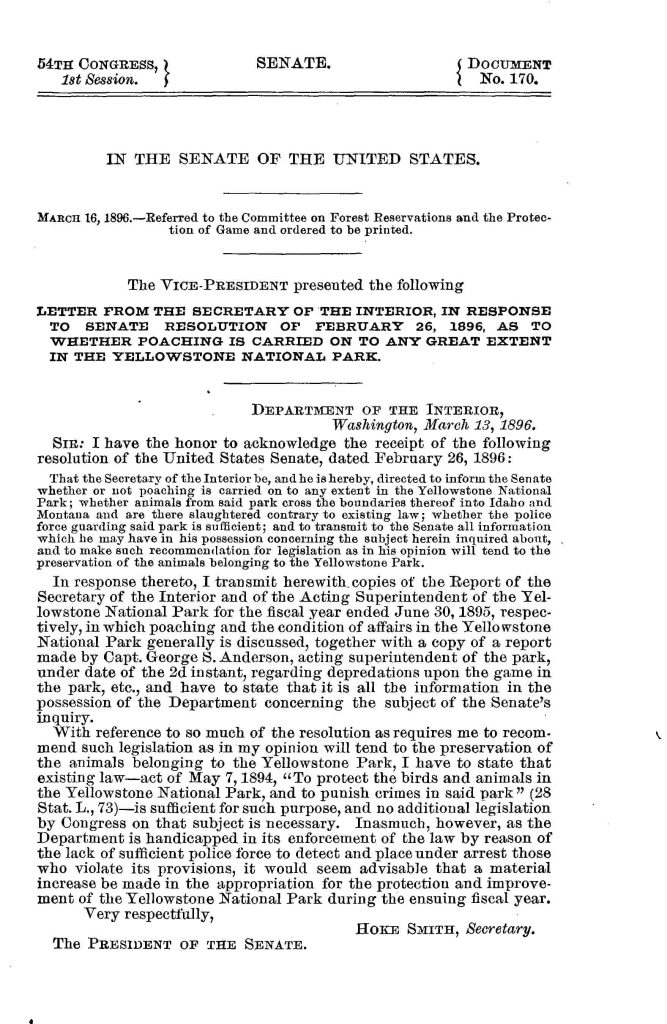

While some royal forests still exist in England, including the famous Sherwood Forest and its venerable 1,000 year old Major Oak, they are today much diminished in size. Many of the venison that roamed their vert, including boars, bears, and wolves, were all hunted to extinction in England by the 16th century. European settlers in the United States eschewed their royal forest heritage, with its ceremonies, taxonomy of the lesser and noble animals of the hunt, chase and warren, and aristocratic privilege. Consequently, hunting regulations in the new United States were virtually nonexistent. As a result, wolves, bison, wild turkeys, and even the now-ubiquitous white tailed deer nearly suffered the same fate as their English cousins due to over-hunting. As the 19th century came to an end, some Americans wondered if any of her wild treasures would survive the next century. Poaching—of bison specifically—was a problem for park police in the young Yellowstone National Park, not even twenty-five years old at the time of this report in 1896.

America’s conservation movement began in earnest with President Theodore Roosevelt, who created the first National Wildlife Refuge at Pelican Island, Florida, in 1903, to protect birds in danger of being hunted to extinction for their fashionable feathers. But it was another Roosevelt who enacted some of the most consequential legislation that still affects hunters—and the wildlife they seek—today.

The Pittman-Robertson Act, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on September 2, 1937, is a major piece of wildlife conservation legislation, created to address habitat and species destruction. Still in effect today, the Act levies an 11% excise tax on all firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment sold in the United States. Money generated by this tax is distributed back to states based on a formula to fund state programs for wildlife conservation and hunter education. Since its passage, the Act has sent over $18 billion from hunters back to state fish and wildlife agencies and is credited with rebuilding populations of white tailed deer and wild turkey. The Act has been so important to the conservation movement that legislation to modernize the Act has been introduced in Congress that would recruit more hunters and recreational shooters as the number of hunters in America diminishes.

An additional testament to its popularity and success, the Pittman-Robertson Act inspired the Dingell-Johnson Act, passed in 1950, which taxes fishing tackle to provide funds for state fish conservation programs, wetlands restoration, and other aquatic management programs.

Another successful piece of wildlife conservation legislation, the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, commonly known as the “Duck Stamp Act,” was again signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 16, 1934. Passed to bolster the already existing but underfunded Migratory Bird Conservation Act, the Duck Stamp Act requires all waterfowl hunters over age 16 in the United States to purchase and carry a Duck Stamp—literally a specially designed postage stamp. While a requirement for waterfowl hunters, anyone can buy a Duck Stamp, which also functions as an annual pass to national wildlife refuges that charge entrance fees, as well as being a beautiful collector’s item for stamp enthusiasts. The Stamp sends ninety-eight cents of every dollar to the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund, which in turn uses the monies to add lands to and maintain the National Wildlife Refuge System. Designs for the stamp are chosen through an art contest that is open to anyone. Stamp sales have generated nearly $1 billion since the program’s inception, restoring 6 million acres of habitat and wetlands, which aid in flood control, reduce soil erosion, and help purify water. In 2013, after a long pilot program, electronic stamps were permanently passed into law to allow customers to skip the post office and buy Duck Stamps online.

Learning Is Always in Season

Here at the HeinOnline, we don’t want information camouflaged from researchers; instead, we strive to present a wealth of content as plainly as if it were wearing hunter orange. Subscribe to the blog to stay in the know on what we’re researching, how we’re finding it, and for ideas to inspire you to flush out your own academic quarry.