If your Netflix algorithm was calibrated toward a certain kind of show circa December 2020, chances are you were prompted to watch Bridgerton. The streaming smash hit, based on author Julia Quinn’s novels, centers around the very attractive and very wealthy Bridgerton family as the single siblings look for love in Regency England, navigating all the social customs, rules, and expectations placed upon people of a certain social standing. While Bridgerton certainly sensationalizes the past, its central world—the social season, presenting debutantes at court, the insular, privileged life of high society (“the ton”) in its ultimate pursuit of a suitable marriage—was very real. Just as the first season of Bridgerton focuses on eldest daughter Daphne coming out into society (a.k.a. announcing to eligible bachelors and their families that she is ready for marriage), so too will this post focus on how society’s rules and laws around marriage affected women.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single researcher in possession of a good mind must be in want of resources. Make sure you’re subscribed to the following databases to find your match:

Matters of Historical Perception

Bridgerton is set during the Regency era of England, which falls between 1811-1820, when King George III was declared unfit to rule and his son ruled as prince regent. Upon George III’s death in 1820, the prince regent became King George IV and thus the new ruler of the United Kingdom; no longer the prince regent, the Regency therefore ended. In the timeline of historical periods in English history, the Regency is considered a subset of the Georgian era (1714-1837) and comes before the Victorian era (1837-1901). In a literary sense, the Regency connotes a time of glamorous elegance, where life was extravagant and full of excess, where problems were more concerned with those of an amorous nature. It owed part of that reputation to its prince regent, who was known to have multiple affairs with multiple women, married and single, and who as a young man had racked up an extraordinary amount of personal debt. It was the time of the Romantics, whose works emphasized nature, individualism and emotion—Wordsworth, Byron, Coleridge, Keats, and Shelley—a time of high fashion, a great revitalization of architecture, and a scandalous culture, where secrets were whispered behind fans as beautiful ladies in lace gowns walk through immaculately manicured gardens.

In reality, the Regency was all this and yet darker. As the inhabitants of Bridgerton’s London are engrossed by Lady Whistledown’s missives, Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated by a Liverpudlian merchant in the House of Commons—the first and only British prime minister to be assassinated. The War of 1812 and the Napoleonic Wars raged, pulling men of all social standing into military service—and leaving less of them at home to marry. 1816 was the Year without a Summer, devastating harvests in England and around the world. The once-booming textile industry slumped off; unemployment increased, wages plummeted and food prices rose sharply. The Peterloo Massacre occurred on August 16, 1819, when eighteen people were killed by charging cavalry sent to break up a crowd of 60,000 people demanding representation in parliament. George IV charged his wife, Queen Caroline, with adultery and attempted to divorce her just before his coronation; a public trial exposing the romantic misdeeds of both monarchs sensationalized the public, who ultimately gave their sympathy to the Queen.

It is not these events that popular memory associates with the Regency era, preferring instead to pair the time with the gossipy sort of romantic entanglements that ensnare the characters of Bridgerton. The original mistress of social commentary and marital navigational pitfalls, Jane Austen, published her works during this time period, although her most famous novels were written and set before the official start of the historical Regency. While Austen’s novels are celebrated for their wit and biting social commentary, at their heart they struggle with the matrimonial consequences of its heroines, both in terms of love and law.

The Season of “Love”

Depending on one’s social standing, marriage could entail more (or less) pomp and circumstance, but the stakes were high for the seamstress and duchess alike. Presentation at court, as happens to Daphne Bridgerton in episode 1, was a real rite of passage for women of a certain rank that existed up until 1958. In order to be presented at court, a girl had to be sponsored by a married female relative who herself at been presented at court; if she had no one, she could rely on a female friend who could apply for her, which included sharing details such as her family name and rank. Approval came from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. Several hundred women were presented at court at the same time, with debutantes curtsying before their sovereign as their name is announced, both for Their Majesties and high society. Now officially “out,” the debutante was considered a “woman of Society” who could partake in all the gaiety of “the season”—summertime balls and dinner parties, but also the Epsom Derby, Royal Ascot, and Wimbledon. But the ultimate purpose of all this partying was to find a “suitable” husband.

Marriage in the Regency, and indeed for much of history, was less an expression of genuine love and more an arrangement designed to produce legitimate heirs and protect estates and fortunes. To “marry well” was less about a lady finding her Prince Charming and more about gaining financial security—especially as primogeniture became the law of the land. Primogeniture is the passing of a family’s entire estate to the eldest son. Entailment was a loophole in instances where a family had no sons to pass the property onto to allow them to transfer the line of succession, so to speak, to another related line within the family, thus at least keeping all their land and wealth within the same family tree; this is the conundrum by which the five Bennett sisters in Pride and Prejudice face the very real possibility of becoming both homeless and destitute upon their father’s death if they do not marry. It is also the same reason why in Bridgerton such attention is paid to whom Anthony, the eldest son and heir to the family’s title and estates, will marry, and why the marital fate of the younger Bridgerton sons is of less concern to their social set, given that none of them will inherit unless Anthony dies.

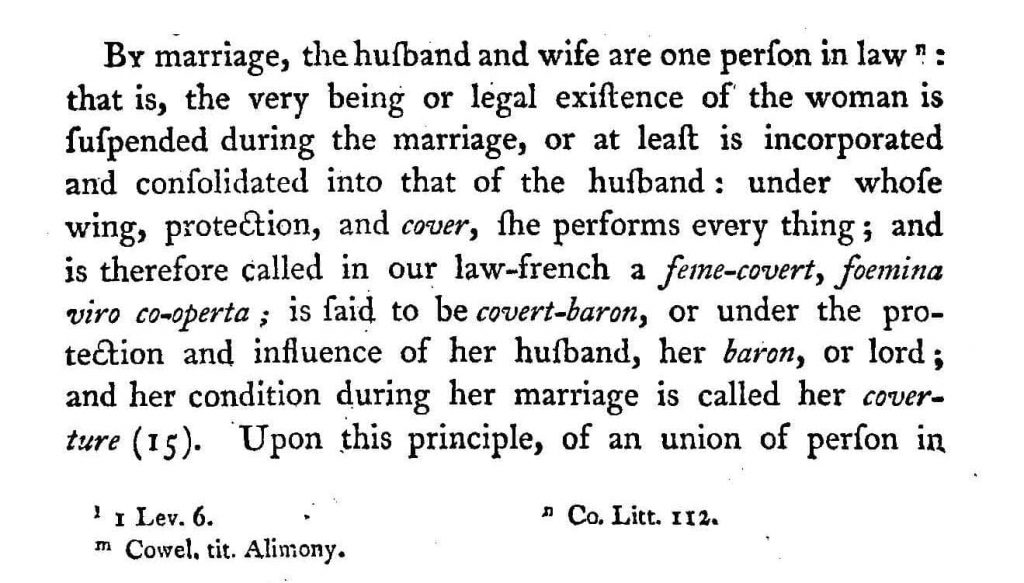

But while marriage was the means for a woman to obtain financial security, it came at a high cost and with very real dangers. As William Blackstone grimly surmised it in his Commentaries on the Laws of England:

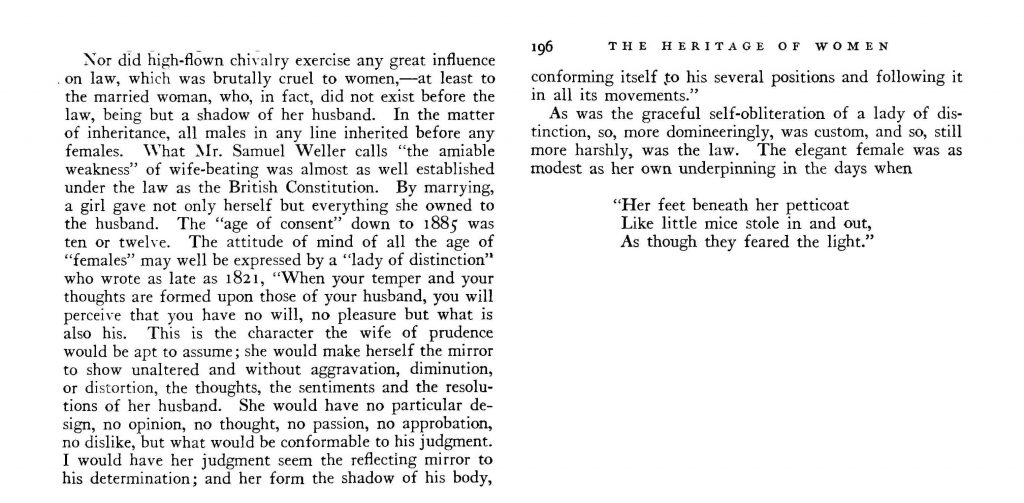

A woman who entered a marriage with property could not dispose of it without the consent of her husband, and if that property earned her money, she wasn’t entitled to that either. All her clothing, jewelry, and any money she had in the bank or in the pocket of a dress belonged to her husband. Husbands had a right to their wife’s bodies, and if a woman left her husband, custody of their children was his legal right. If a married woman wanted to seek the aid of the courts and sue her husband or any other person who had legally wronged her, she couldn’t do that either. A husband could beat his wife, so long as he did not maim or kill her. This legal status—or lack thereof—was known as coverture and gets its basis from the idea that, once married, a woman was supposed to be under the complete protection of her husband: she was his responsibility. Men, especially men of higher social standing, were allowed to have affairs and even live entirely apart from their wives and children, so long as he continued to financially support them; women, of course, were not granted the same freedom, a hypocrisy that plays out in the trial of Queen Caroline.

Reckonings and Reformation

Marriage laws and customs of the time were chiefly derived from the “Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriages,” commonly known as Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act 1753. Prior to the Act’s passage, a legal marriage could take place so long as both parties were of legal age (twelve years old for girls, fourteen for boys), weren’t already married, and weren’t related in a taboo way (e.g., brother and sister). Following the Act, parental consent was required for parties under the age of twenty-one. Marriage could take place after a publication of the banns (the public announcement of an impending marriage) or by being granted a special, hard-to-obtain license, and they had to be officiated by an Anglican minister. Couples hoping to escape the Act’s reach traveled to Scotland to be married. The Act remained in effect until it was relaxed by the Marriage Act 1836, which allowed for secular civil marriages.

Things slowly began to improve as time crept towards the Victorian era. The Custody of Infants Act 1839 allowed a woman to petition the courts for custody of her children. The great champion of maternal custody rights at the time was Caroline Norton, whose work helped lead to the Act’s passage. Norton came from a well-to-do family; her grandparents were Irish peers and prominent playwrights. She was unhappily married to her husband, George, and when they separated he barred her from seeing their children. Her husband accused her of having an affair with her friend, the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, creating a scandal that found its way into court. Using her social connections, Caroline began an intense crusade for maternal rights, writing pamphlets distributed to members of Parliament.

Norton’s activism also extended to reforming the law on divorce. Civil divorce was finally permitted with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. While divorce had been in existence prior to the Act, in practical applications it was nonexistent, since obtaining a divorce required an act of Parliament; just prior to its passage, only 4 or 5 divorces were granted a year between 1851-1857. The Act was not a perfect step towards equality between the sexes, requiring a higher burden of proof for a woman wanting to divorce her husband for adultery compared to him wanting to divorce her for the same reason.

Women’s marital rights further improved with the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act 1870, another cause worked on by Caroline Norton, which allowed married women to keep property and any money they earned, finally ending the doctrine of coverture.

Find Your Match

Make the perfect match for your inbox and subscribe to the HeinOnline blog to be courted with new posts every time we publish. Multiple authors write for the HeinOnline blog to keep you up-to-date on new additions, the latest research tips and tricks, and with posts like these showing the endless variety of content within HeinOnline to keep you entertained and maybe make you a little bit smarter.