Movie fans, rejoice. After multiple delays, No Time to Die, the latest James Bond film, is finally in theaters. No Time to Die is Eon Productions’ 25th film in the Bond canon and the last film in Daniel Craig’s tenure as 007, and, based on critic reviews, it was worth the pandemic-induced wait. The Bond film canon has endured since 1962, when Sean Connery first appeared as 007 in Dr. No, taking Ian Fleming’s spy out of the novel and onto the silver screen. Since Dr. No, five other actors have shaken a martini and holstered a Walther PPK for Queen and country. But as often happens in a long-enduring and hugely profitable enterprise, conflicts in the courtroom over who is owed a piece of MI6’s most famous agent have given Bond adversaries other than Blofeld and SPECTRE. So stick a red carnation in your buttonhole and climb inside this DB5 for an exploration of the James Bond franchise with HeinOnline.

Make sure you have the following gadgets from Q branch to complete your mission:

Tales from Goldeneye

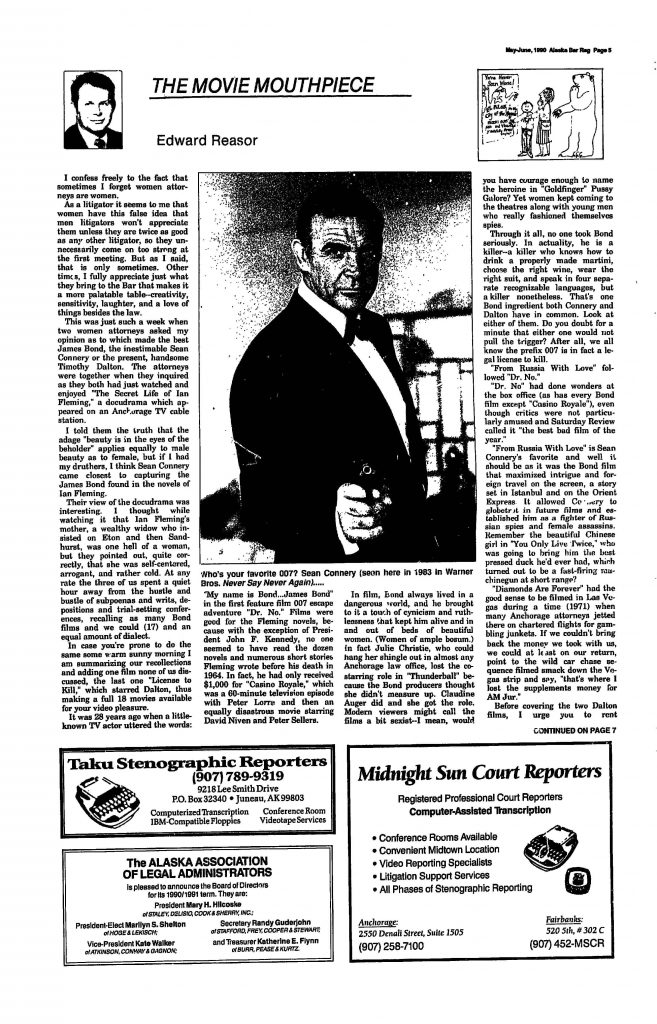

In the winter of 1952, Ian Fleming was at Goldeneye, his Jamaican estate, looking for a distraction from his forthcoming wedding. He was 43, a well-heeled descendant of bankers who as a young man had done brief educatory stints at Eton College and Sandhurst[1]Edward Reasor, The Movie Mouthpiece, 14 ALASKA B. RAG 5 (1980). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Bar Journals Library. before posting to Moscow as a Reuters reporter in the 1930s. During World War II, Fleming was recruited to be the personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence. Here, Fleming had a front line role in plans to capture codes to the legendary Nazi Enigma machine and directed a unit of commandos whose missions included securing enemy documents ahead of advancing Allied troops. After the war, Fleming returned to the newspaper business, overseeing the Kemsley newspaper group’s foreign correspondents, but set himself a leisurely schedule; Fleming took a three-months’ vacation every year, escaping London’s cold winters for the beaches of Jamaica. It was here at Goldeneye that Fleming finally wrote the spy novel he had been toying with penning for years. That novel was Casino Royale, and when it was published in 1953 the world was introduced to James Bond.

Every winter, Fleming returned to Goldeneye to write the next Bond adventure, eventually penning a total of thirteen novels and two short stories. But almost from the beginning, Fleming envisioned his literary creation being adapted for film. In 1954, a one-hour television adaptation of Casino Royale aired on CBS, starring Barry Nelson as an Americanized Jimmy Bond squaring off at the baccarat table with Peter Lorre’s Le Chiffre. But Fleming wanted more. He sold the film rights to Casino Royale to the Russian actor Gregory Ratoff,[2]Paul C. Weiler. Entertainment, Media, and the Law: Text, Cases, Problems (3). This document is located in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. but Ratoff was never able to persuade anyone to make a movie about a little-known English spy. In 1959, Fleming was introduced to Irish producer Kevin McClory. Together with screenwriter Jack Whittingham, they wrote an original screenplay[3]Elaine W. Shoben; et al. Remedies: Cases and Problems (4). This document is located in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. that took Bond on an aquatic caper to stop a nuclear bomb that had fallen into the hands of a new, different sort of enemy: an international criminal organization known as SPECTRE, led by Ernest Stavro Blofeld.

The script, however, never materialized into a finished film. Not willing to let a good idea go to waste, Fleming took the screenplay and expanded upon it,[4]Anthony J. Casey & Andres Sawicki, Copyright in Teams, 80 U. CHI. L. REV. 1683, 1711 (2013). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. publishing it as the eighth Bond novel in 1961. That book was Thunderball. But in what would prove to be a disastrously critical error, Fleming did not give writing credit to either McClory or Whittingham, and, maybe even more egregiously, did not secure their permission[5]Anthony J. Casey & Andres Sawicki, Copyright in Teams, 80 U. CHI. L. REV. 1683, 1711

(2013). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to novelize their screenplay. Unsurprisingly, McClory sued.

Expecting Mr. Bond

1961 was a crucial year in the history of James Bond. While Ian Fleming was tied up in litigation over Thunderball, he was finally having some success with regards to realizing his cinematic dreams. Producers Harry Saltzman and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli—the latter of whom may or may not have been involved in the death of Three Stooges creator Ted Healy—teamed up to bid for the film rights to James Bond. Saltzman and Broccoli formed two production companies to handle the deal: Eon Productions, through which they eventually secured distribution and financing for the Bond films from United Artists, and Danjaq, the holding company for Eon and the various copyrights and trademarks of the James Bond cinematic universe. In the end, Fleming signed over to Saltzman and Broccoli the exclusive film rights[6]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. to all his existing Bond novels—sans Casino Royale—and to any future Bond novels.

There was just one problem: the first book Saltzman and Broccoli wanted to adapt was Thunderball, going so far as to commission screenwriter Richard Maibaum[7]263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase to pen a new screenplay. But Thunderball was still tied up in the courts, so the two producers moved on to Dr. No, releasing the film in 1962.

Fleming and McClory eventually settled[8]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. their dispute over the ownership of Thunderball in 1963. The settlement acknowledged Fleming as the “creator and proprietor” of James Bond,[9]Paul C. Weiler. Entertainment, Media, and the Law: Text, Cases, Problems (2). This document can be found in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. but that McClory was the “joint author of the story comprising the film script” [10]Paul C. Weiler. Entertainment, Media, and the Law: Text, Cases, Problems (2). This document can be found in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. that Fleming had turned into the novel Thunderball. The settlement gave McClory the Thunderball movie rights and the “exclusive rights to re-produce any part of the novel in cinematographic films and to exhibit any such films in any manner whatsoever and for the purposes of making any such films to make scripts involving and part of said novel.”[11]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

The protracted litigation over Thunderball had taken a toll on Ian Fleming, both creatively and physically. Fleming was the only man who could rival James Bond’s smoking and drinking habits, and he had a heart attack in 1961 from which he never fully recovered. In 1964, approximately eight months after settling the Thunderball suit, Fleming suffered another heart attack. He died[12] Dirk Vanover, Methods for Protecting Public Domain Characters after Klinger v. Doyle Estate, Ltd., 33 ENT. & SPORTS LAW. 49, 53 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. on August 12, 1964, at the age of 56.

Your SPECTRE Against Mine

When Ian Fleming died in 1964, Saltzman and Broccoli had released two James Bond films: Dr. No (1962) and From Russia with Love (1963), with the third, Goldfinger, being released just a month after Fleming’s death. The two producers now wanted to move on to the Bond film they had always intended to make, Thunderball, but to do so they needed to bring Kevin McClory on board. In exchange for the exclusive Thunderball rights for a ten-year period, McClory was included as a producer on the film. It made McClory a rich man; Thunderball smashed the previous box office hauls for the franchise and, adjusted for inflation, it is still the highest-grossing James Bond film to date.

Over the next decade, the Bond machine hummed along. Connery made one more Bond film, You Only Live Twice (1967), before briefly stepping down; after George Lazenby’s turn in the excellent On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), in which Bond infiltrates a nefarious health club in the Alps run by Blofeld and SPECTRE, Connery returned for one last film, 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever. In 1972, Jack Whittingham, the third man who had worked on the Thunderball script, died, leaving McClory the last claimant from the suit still alive. Roger Moore’s tenure as 007 began with Live and Let Die (1973), and around this time the rights to the Thunderball story reverted to McClory. Danjaq released four more James Bond films starring Roger Moore: The Man with the Golden Gun (1974), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Moonraker (1979), and For Your Eyes Only (1981), and were preparing to release a new Bond film in 1983. But so was Kevin McClory.

Kevin McClory had been working on his Thunderball remake since the 1970s. The two parties traded legal victories throughout the decade; Danjaq and United Artists briefly succeeded[13]26 BULL. COPYRIGHT SOC’Y U.S.A. 377, 429 (1979). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in preventing McClory from releasing his own Bond movie, while McClory in turn tried to stop the release of The Spy Who Loved Me.[14]Daniel Sheerin, You Never Got Me Down, Delay: Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. and the Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought within the Statute of Limitations, 24 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 851, 878 … Continue reading Although unsuccessful, Danjaq was forced to rework the script to remove[15]263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. the characters of Blofeld and SPECTRE. In a coup, McClory coaxed Sean Connery out of retirement to reprise the role of James Bond for his new film, titled Never Say Never Again. MGM, which had acquired United Artists in 1981, joined with Danjaq to stop the film’s release, but were unsuccessful; Never Say Never Again was released in 1983, the same year as the sixth Roger Moore Bond film, Octopussy.

Despite the competition, Octopussy outgrossed[16]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 392 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. its rival Bond movie. Roger Moore stepped down from the role after 1985’s A View to a Kill, and Timothy Dalton was tapped for a darker, grittier interpretation of 007. But the 1980s also saw more litigious rumblings from Kevin McClory, including attempts to get the copyright registration[17]263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. for the novel version of Thunderball corrected to list himself as a co-author, and placing full page ads in Variety[18]263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. asserting that Danjaq and MGM were infringing on his rights to James Bond. In 1989, around the same time the second Timothy Dalton Bond film, License to Kill, was released, McClory was shopping around production for another competing Bond film,[19]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 393 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. getting as far as scouting locations before MGM threatened McClory with legal action if he did not desist. But throughout the Pierce Brosnan tenure of Bond films in the 1990s, McClory never abandoned his intentions to make more movies using his Thunderball claims. In 1997, he licensed his rights to Sony[20]23 ENT. L. REP. 1, 17 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal

Library. with the intention of making a competing line of Bond films. Unsurprisingly, Danjaq and MGM immediately sued to stop them from doing so.

The case, Danjaq LLC v. Sony Corp.,[21]263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. considered the questions of what made James Bond James Bond[22]Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 416 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and who was responsible for those qualities. The Bond of Ian Fleming’s books didn’t have ingenious (and outlandish) gadgets supplied by Q branch. There were few witty one-liners and none of the pigeon doubletake humor common to the Roger Moore movies. In the books, Bond doesn’t even drive an Aston Martin, let alone one outfitted with bulletproof glass and machine guns. The literary Bond is described as “cold” and “cruel,” a handsome-ish man who resembled Hoagy Carmichael, with a scar on his face and a “comma” of black hair. By contrast, McClory argued that the cinematic James Bond, the one who had been hugely profitable for Danjaq and MGM, was derived from his treatment of the character in that first, aborted Thunderball script written thirty years ago.

MGM and Sony settled just before the case proceeded to trial, with Sony agreeing not to make any James Bond movies[23]David Goldberg, Robert W. Clarida & Thomas Kjellberg, Recent Developments in Copyright: Selected Annotated Cases, 49 J. COPYRIGHT SOC’Y U.S.A. 707, 799 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and reimbursing Danjaq and MGM for their legal bills. In return, Danjaq and MGM agreed to pay Sony $10 million for the rights to Casino Royale. Sony owned the Royale rights thanks to the circuitous journey they had taken after Ian Fleming sold them to Gregory Ratoff in 1955; eventually, in 1967, Sony-owned Columbia Pictures released a satiric Casino Royale starring David Niven, Peter Sellers, and Woody Allen (yes, this is a real movie).

Undeterred by Sony bowing out of the suit, McClory persisted,[24]Daniel Sheerin, You Never Got Me Down, Delay: Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. and the Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought within the Statute of Limitations, 24 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 851, 878 … Continue reading claiming he was owed not only the right to James Bond, but to a share of the billions of dollars “his” character had made for Danjaq and MGM. When the district court ruled against McClory,[25]Daniel Sheerin, You Never Got Me Down, Delay: Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. and the Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought within the Statute of Limitations, 24 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 851, 878 … Continue reading he appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

From the Ninth Circuit with Love

In 2001, the Ninth Circuit ruled against McClory, citing, as the district court had done, the doctrine of laches.[26]David S. Garland, et al., American and English Encyclopaedia of Law (2). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. Laches is an equitable defense doctrine that allows a defendant to claim that, because the claimant waited so long to make a claim, by virtue of his tardiness he has no standing. The court calculated a period of delay of either thirty-six years (dating McClory’s claim back to the release of Dr. No) to nineteen years (dating it to his suit against The Spy Who Loved Me). At no point in either timespan had McClory brought suit to stop any of the original films from being released. While all that time passed, valuable witnesses and vested participants, including Ian Fleming, Jack Whittingham, Harry Saltzman, Alfred “Cubby” Broccoli, and Richard Maibaum, had died, and important documents[27]Brief for the Motion Picture Association of America Inc., et al., as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents at 14, Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., 572 U.S. 663 (2013) (No. 12-1315). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of U.S. … Continue reading that could have helped Danjaq’s case had been lost. To the court, it appeared McClory had waited until James Bond had turned into the film franchise with the golden goose. Further, the court found no “willful infringement” on the part of Danjaq with regards to the “cinematic” James Bond McClory claimed to have created, finding:

Indeed, Danjaq was not on notice before the current litigation that McClory claimed a right in the supposed cinematic iteration of the James Bond character. The Bond character had been developed by Fleming over the course of six years and seven books before McClory came into the picture. Even assuming that McClory reinvented the Bond character in the Thunderball script materials, there was simply no way for Danjaq to know that McClory was laying claim to such a property. Given that lack of notice, and the absence of evidence of willfulness, a jury could not find willful infringement.

In 2004, Sony acquired MGM. Now, thanks to Sony’s sale of the Casino Royale rights to Danjaq and MGM, and with MGM being acquired by Sony, Ian Fleming’s first novel finally received the Danjaq treatment in the 2006 movie starring Daniel Craig. Kevin McClory died in 2006, and in 2013, Danjaq and MGM acquired all rights and interests in McClory’s estate, officially putting an end to the litigious sparring that had marred the Bond franchise almost since its inception. With the reacquisition, perhaps the most iconic of Bond villains, Bloefeld and his criminal organization, were able to return in 2015’s Spectre.

Pay Attention, 007

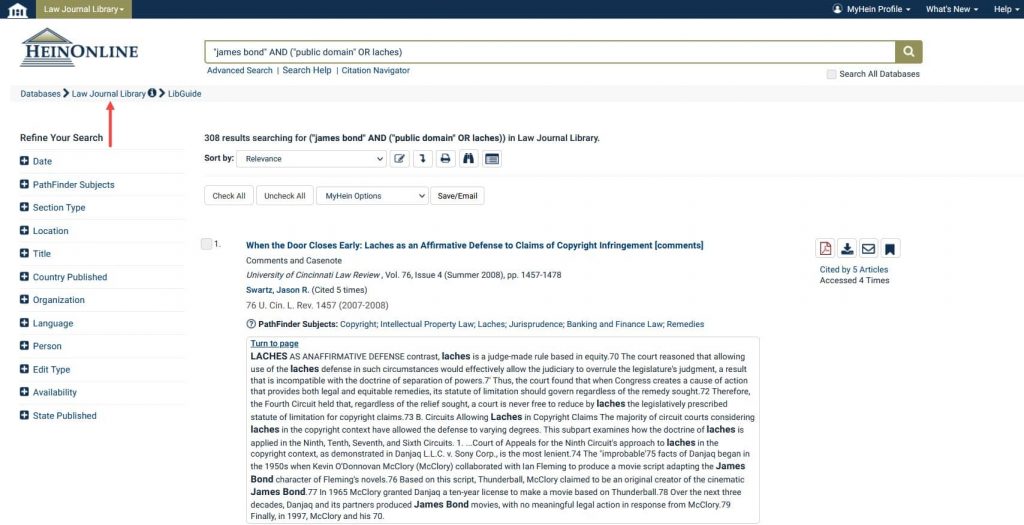

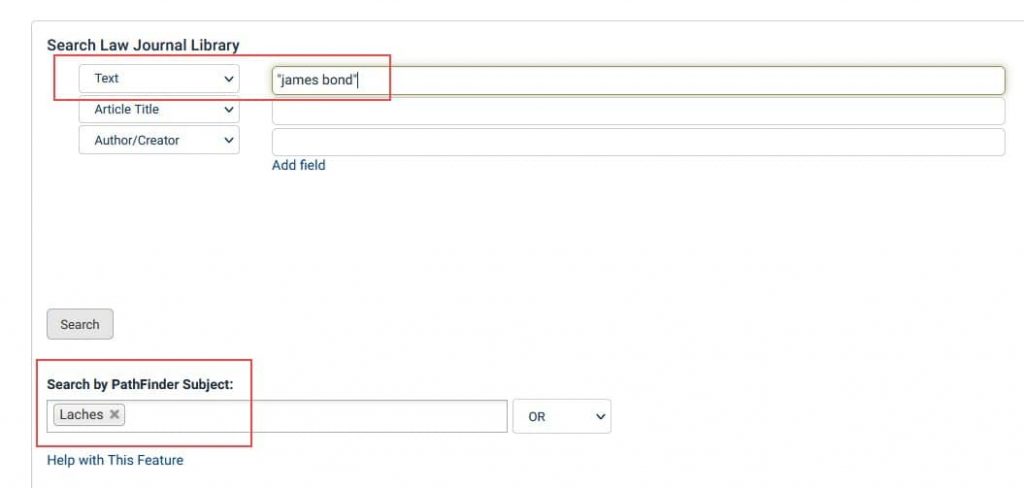

We’ve just scratched the surface on the topic of copyright of beloved fictional characters and how the doctrine of laches has been applied to other entertainment media. While we may return to this topic again in a future blog post, you can take the research further with this sample search in the Law Journal Library.

There is even a dedicated laches subject within PathFinder. Use the Advanced Search feature to search for articles related to James Bond within the Laches subject.

Have your own favorite fictional character? Try plugging him or her into the main search bar and selecting the “Just search for” option that will autopopulate. You never know what you might find.

License to Learn

Did you enjoy this post? We hope you did! The HeinOnline bloggers are always coming up with creative ways to show off the breadth of content in HeinOnline and its applicability to a number of topics and areas of research, some of which you might not have even considered. If you found this post enjoyable, hit the subscribe button below to receive every new blog post directly to your inbox.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Edward Reasor, The Movie Mouthpiece, 14 ALASKA B. RAG 5 (1980). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Bar Journals Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul C. Weiler. Entertainment, Media, and the Law: Text, Cases, Problems (3). This document is located in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. |

| ↑3 | Elaine W. Shoben; et al. Remedies: Cases and Problems (4). This document is located in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. |

| ↑4 | Anthony J. Casey & Andres Sawicki, Copyright in Teams, 80 U. CHI. L. REV. 1683, 1711 (2013). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑5 | Anthony J. Casey & Andres Sawicki, Copyright in Teams, 80 U. CHI. L. REV. 1683, 1711 (2013). This article is located within HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | 263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase |

| ↑8 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9, ↑10 | Paul C. Weiler. Entertainment, Media, and the Law: Text, Cases, Problems (2). This document can be found in a forthcoming HeinOnline database, West Academic Casebook Archive Collection. |

| ↑11 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 391 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑12 | Dirk Vanover, Methods for Protecting Public Domain Characters after Klinger v. Doyle Estate, Ltd., 33 ENT. & SPORTS LAW. 49, 53 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13 | 26 BULL. COPYRIGHT SOC’Y U.S.A. 377, 429 (1979). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14, ↑24, ↑25 | Daniel Sheerin, You Never Got Me Down, Delay: Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. and the Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought within the Statute of Limitations, 24 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT. L.J. 851, 878 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15, ↑17, ↑21 | 263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑16 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 392 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18 | 263 F.3d 942 (9th Cir. 2001). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑19 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 393 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑20 | 23 ENT. L. REP. 1, 17 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑22 | Keith Poliakoff, License to Copyright: The Ongoing Dispute over the Ownership of James Bond, 18 CARDOZO ARTS & ENT. L.J. 387, 416 (2000). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑23 | David Goldberg, Robert W. Clarida & Thomas Kjellberg, Recent Developments in Copyright: Selected Annotated Cases, 49 J. COPYRIGHT SOC’Y U.S.A. 707, 799 (2002). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑26 | David S. Garland, et al., American and English Encyclopaedia of Law (2). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑27 | Brief for the Motion Picture Association of America Inc., et al., as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents at 14, Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., 572 U.S. 663 (2013) (No. 12-1315). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of U.S. Supreme Court Cases. |