In recent weeks, news about Title 42 being brought to an end has been on virtually every media platform. But what is Title 42, why did it end, and what does it mean for migrants seeking asylum in the United States moving forward? Let’s explore the laws and policies using resources from HeinOnline, including our U.S. Code and Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. databases.

The History of Title 42

Title 42 refers to a section of the United States Code that grants certain powers to the federal government in the name of protecting public health. Established as part of the Public Health Service Act[1]To consolidate and revise the laws relating to the Public Health Service, and for other purposes., Public Law 78-410 / Chapter 373, 78 Congress. 58 Stat. 682 (1944). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. of 1944, the Code states:[2]1946 Edition v.3 Titles 27-42 4586 (1946) Sections 265 – 270. This section of the U.S. Code can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database.

Whenever the Surgeon General determines that by reason of the existence of any communicable disease in a foreign country there is serious danger of the introduction of such disease into the United States, and that this danger is so increased by the introduction of persons or property from such country that a suspension of the right to introduce such persons and property is required In the interest of the public health, the Surgeon General, in accordance with regulations approved by the President, shall have the power to prohibit, in whole or In part, the introduction of persons and property from such countries or places as he shall designate in order to avert such danger, and for such period of time as he may deem necessary for such purpose.

Until 2020, Title 42 had never been invoked before. A law preceding it, a statute from 1893,[3]Granting additional quarantine powers and imposing additional duties upon the Marine-Hospital service., Chapter 114, 52 Congress, Public Law 52-114. 27 Stat. 449 (1893). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. was only used once, in 1929, to prevent migrants from certain countries from entering the United States during a meningitis outbreak.[4]1 2 (December 12, 2022) COVID-Related Restrictions on Entry into the United States under Title 42: Litigation and Legal Considerations. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention invoked Title 42[5]Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Remarks at a White House Coronavirus Task Force Press Briefing , Daily Comp. Pres. Docs. 1 (2020). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. by allowing U.S. officials to turn away migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, stating that it was an attempt to curb the spread of disease—however, some suspected that this was an attempt by the Trump administration to restrict immigration.[6]1 7 (2022) Examining Title 42 and the Need to Restore Asylum at the Border: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Border Security, Facilitation, and Operations of the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Seventeenth … Continue reading Previously, immigrants had been able to cross the border illegally and seek asylum, after which they would be screened and wait for their immigration case in the U.S. However, Title 42 meant that immigrants would now be sent back to Mexico and denied the ability to seek asylum—and this happened more than 2.8 million times in the span between March 2020 and May 2023, when Title 42 ended. However, families and minors traveling alone were exempt from the restrictions, and migrants were able to attempt crossing multiple times without repercussions.

When Did it End?

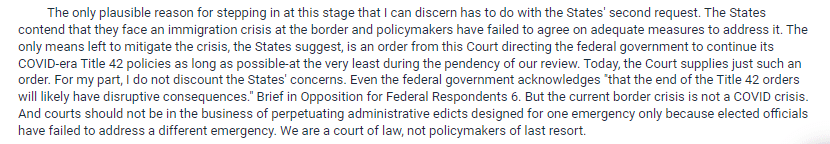

Biden’s administration attempted to end Title 42 in 2022, but several Republicans sued, stating that it was necessary to ensure border security. A federal judge agreed to block the termination. It was again scheduled to end in December 2022, with a federal judge calling Title 42 “arbitrary and capricious,”[7]Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas, Civil Action No. 21-100 (EGS) (United States District Court, District of Columbia 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase. but the Supreme Court put a pause on it in the case Arizona v. Mayorkas.[8]Arizona v. Mayorkas, 598 U.S. ____. (United States Supreme Court, 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase.

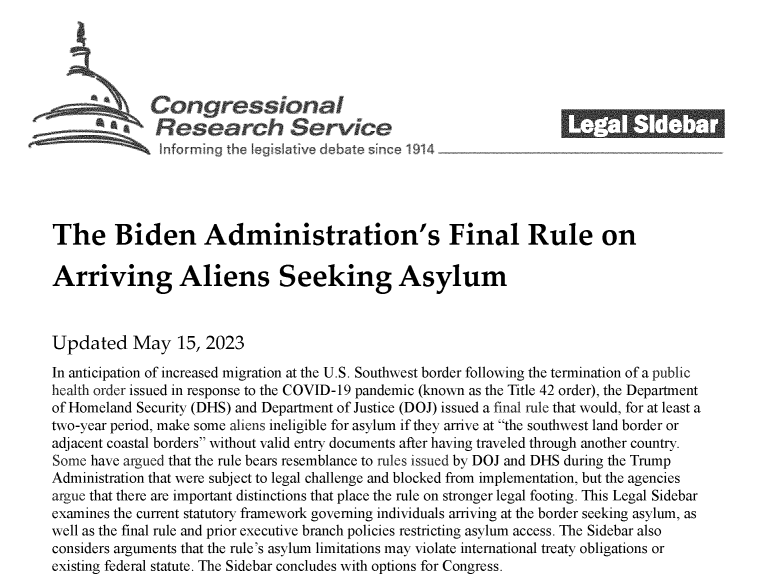

Then, in April 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that there was no public health risk in ending the restrictions under Title 42, and in January 2023, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the end of the national COVID-19 public health emergency.[9]1 11 (2023) Brief of Federal Respondents. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of U.S. Supreme Court Cases database. Thus, Title 42 was scheduled to end at 11:59 p.m. ET on May 11.[10]1 2 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

What Happens Now?

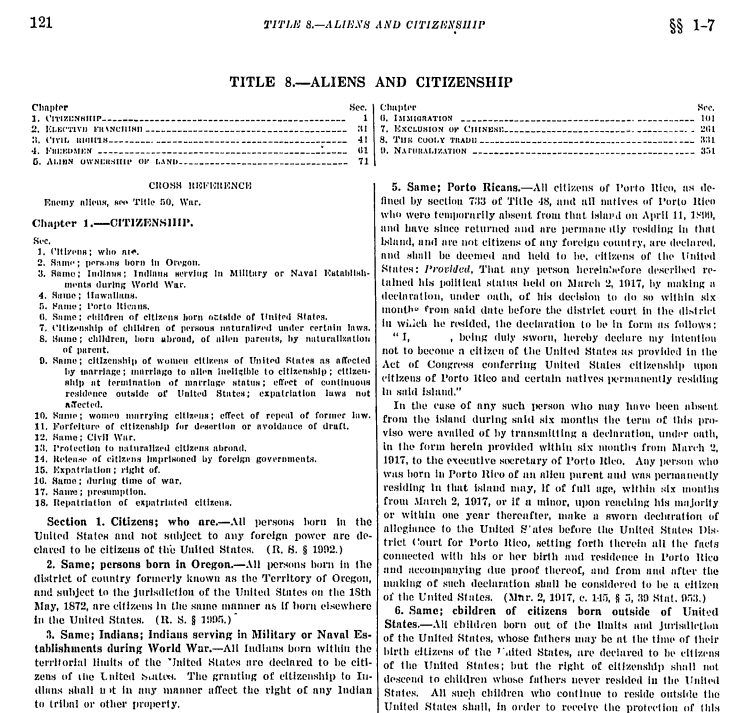

Now that Title 42 has been lifted, we revert back to Title 8,[11]2018 Edition v. 4 Titles (7-10) 579 (2018) Aliens and Nationality. This section of the U.S. Code can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. which is the section of the U.S. Code that contains immigration policies.

Under Title 8, all immigrants who request asylum must be provided with either a preliminary interview, or an opportunity to meet with an immigration judge. Migrants remain in border patrol custody until asylum officers determine whether they will be accepted or deported. Some will receive a notice to appear in court and in the meantime will be released into the U.S. or into long-term detention centers. However, immigration court systems are currently so behind that those with court notices will likely need to wait years to be granted asylum. Migrants who don’t claim asylum or who fail their interview face deportation.

Biden has established new policies to reduce illegal immigration and smuggling.[13]1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. For example, now, any migrant who is caught crossing the border illegally will not be able to return to the United States for five years, at the risk of criminal prosecution.

Additionally, the Biden administration has set rules that make qualifying for asylum more difficult. For example, now anyone seeking asylum in the United States who didn’t apply online first or seek protection in a country that they traveled through,[14]1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. risk being turned away. These policies are similar to those initially suggested by the Trump administration[15]1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. that had been struck down by courts. In response to the Biden policy, the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies and other advocacy groups have filed a lawsuit in federal court.

As a result of the ending of Title 42, several cities in Texas have issued emergency declarations as migrants are released into border cities. Additionally, Texas governor Greg Abbott and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis have both been busing and flying migrants to Democrat-run cities,[16]168 Cong. Rec. H8013 (2022). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. such as Martha’s Vineyard and Washington, D.C. in retaliation.

Who Is Allowed in the United States?

Under these new policies, up to 30,000 migrants per month will be allowed in the United States from Venezuela, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Cuba.:[17]1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. Each person seeking asylum must have a sponsor in the United States and meet other criteria. They will be allowed to remain in the U.S. for up to two years through a parole grant.

Additionally, up to 100,000 migrants will be allowed from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Each migrant from these countries must have family in the United States and must apply online. Anyone who doesn’t follow these policies risks deportation to Mexico. To assist in immigration efforts, Customs and Border Protection’s CBP One app allows migrants in central or northern Mexico to schedule inspection appointments.

Anyone entering the United States at the U.S. Mexico border without valid documents after traveling through a country other than their country of residence or citizenship, must meet certain exceptions or be ineligible for asylum. These exceptions include:[18]1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database.

- Authorization under a Department of Homeland Security-approved parole process

- Arrived for inspection with an appointment made through the CBP One app, or able to show proof that the app was impossible to access due to language, technical, or other obstacles

- Applied for asylum in another country they had traveled through but were denied

However, unaccompanied minors are exempt from these rules—they are transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services when they reach the border.

Plans are in the works to set up a number of immigration processing stations[19]88 Fed. Reg. 1255 (2023), Monday, January 9, 2023, pages 1133 – 1321. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. throughout Latin America, including Colombia and Guatemala. These stations would allow immigrants to be assessed for eligibility to resettle in those countries, or in the United States, Canada, or Spain.

Explore Immigration in the United States with HeinOnline

Continue your research on the history and current state of immigration in America with HeinOnline’s Immigration Law & Policy in the U.S. This database includes more than 4,000 titles and 1.5 million pages spanning across hearings, reports, decisions, acts, and legislative histories, as well as the entirety of Title 8 of the U.S. Code, creating the first comprehensive database of its kind in a fully searchable format!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | To consolidate and revise the laws relating to the Public Health Service, and for other purposes., Public Law 78-410 / Chapter 373, 78 Congress. 58 Stat. 682 (1944). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 1946 Edition v.3 Titles 27-42 4586 (1946) Sections 265 – 270. This section of the U.S. Code can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. |

| ↑3 | Granting additional quarantine powers and imposing additional duties upon the Marine-Hospital service., Chapter 114, 52 Congress, Public Law 52-114. 27 Stat. 449 (1893). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑4 | 1 2 (December 12, 2022) COVID-Related Restrictions on Entry into the United States under Title 42: Litigation and Legal Considerations. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑5 | Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Remarks at a White House Coronavirus Task Force Press Briefing , Daily Comp. Pres. Docs. 1 (2020). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |

| ↑6 | 1 7 (2022) Examining Title 42 and the Need to Restore Asylum at the Border: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Border Security, Facilitation, and Operations of the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, Second Session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑7 | Huisha-Huisha v. Mayorkas, Civil Action No. 21-100 (EGS) (United States District Court, District of Columbia 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑8 | Arizona v. Mayorkas, 598 U.S. ____. (United States Supreme Court, 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑9 | 1 11 (2023) Brief of Federal Respondents. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Preview of U.S. Supreme Court Cases database. |

| ↑10 | 1 2 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑11 | 2018 Edition v. 4 Titles (7-10) 579 (2018) Aliens and Nationality. This section of the U.S. Code can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. |

| ↑12 | 1925-1926 Edition, Titles 1-50 121 (1925-1926) Sections 1-7. This section of the U.S. Code can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. |

| ↑13, ↑14, ↑15, ↑17, ↑18 | 1 1 (May 15, 2023) Biden Administration’s Final Rule on Arriving Aliens Seeking Asylum. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑16 | 168 Cong. Rec. H8013 (2022). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑19 | 88 Fed. Reg. 1255 (2023), Monday, January 9, 2023, pages 1133 – 1321. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |