New York State’s Adirondack Park is the largest state park outside of Alaska, consisting of six million acres of protected land in Upstate New York. Centering on the Adirondack Mountains, the park encompasses vast areas of forest, including some of the largest old growth forests East of the Mississippi, dotted with hundreds of glacial lakes. The Park is home to a diverse population of wildlife, including moose and bear, and innumerable species of plants. It is also home to more than 100,000 people who live there year-round, with many thousands more flocking to the region in the summer.

This human population is one of the most noteworthy features of New York’s Adirondack Park, which holds unique status under the New York State Constitution. In the Adirondack Park, approximately 43 percent of the land is owned by the state, with the remaining 57 percent belonging to private landowners, including large business interests. The balancing act between preservation and exploitation has been one of the defining characteristics of the park since its establishment in 1892.

Keep reading, as we explore the history of the Adirondack Park, using HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library, State Constitutions Illustrated, United States Statues at Large, and Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collections.

Early History of the Adirondacks

As far as mountains go, the Adirondacks are relatively young, having emerged a mere five million years ago, and shaped into their present arrangement by the ebb and flow of glaciers. Unlike most mountain ranges in North America, which are typically linear, the Adirondacks form a 160-mile wide circle, often referred to as the Dome. There is a long history of human habitation in the Adirondacks, with some archaeological sites in the region dating as far back as 9,000 BCE. In more recent history, the Adirondack region served as a shared hunting ground for a number of Indigenous nations, including the Mohicans and the Mohawk, of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy have historically been referred to as the “Iroquois” by European settlers. The term is still widely used by some at present. However, this term is not preferred by the Six Nations, and is widely considered to be derogatory in origin. The name “Adirondack” also has a possibly derogatory origin, as it is supposedly derived from an anglicization of the Mohawk word for the Mohicans, translating to “bark eater,”[1]Frederick Webb Hodge. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (1912). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. in reference to the Mohicans’ putative habit of eating trees in times of scarcity. The geologist Ebenezer Emmons is credited with hearing this word and being the first to apply it to the mountains of the region in 1838.

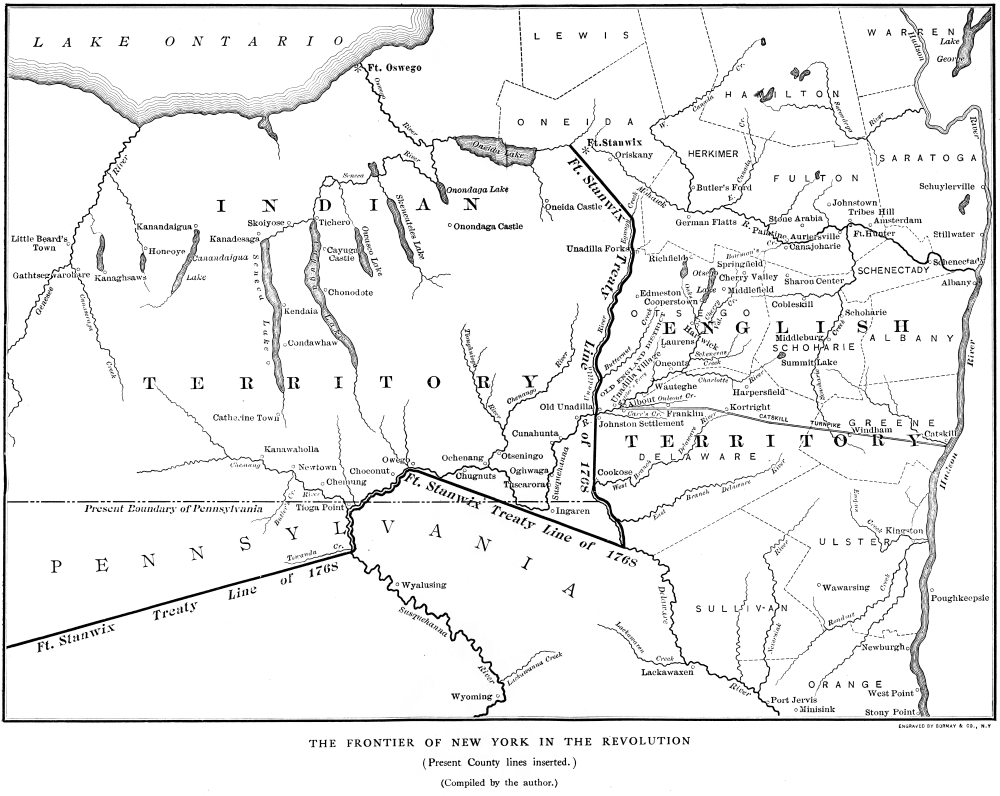

European settlers began to enter the region in the 17th and 18th centuries, beginning a centuries-long process of forcible displacement of Indigenous peoples, often under the guise of coercive treaties between colonial powers (and later the United States) and the Haudenosaunee. In 1768, in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix,[2]E.B. O’Callaghan. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York; Procured in Holland, England and France (1857). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. a boundary line was established dividing British lands in the Thirteen Colonies from those held by indigenous nations, situating the Adirondacks within territory allocated to settlers. Following the American Revolution, during which the majority of the Haudenosaunee allied with the British, settler control over the land was further consolidated through a series of treaties between the American government and the Six Nations: in particular the Treaty of Canandaigua[3]Treaty with the Six Nations, . 7 Stat. 44 (1794). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s United States Statutes at Large collection. in 1794, and the Treaty with the Mohawk [4]Mohawks: Relinquishment by the Mohawks of all claims to land in the State of New York, 7 Stat. 61 (1797). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s United States Statutes at Large collection. in 1797.

The New York Forest Preserve

In the immediate aftermath of the American Revolution, New York State began selling off its public lands en masse, with most being sold to private interests by 1820.[5]Louise A. Halper, A Rich Man’s Paradise: Constitutional Preservation of New York State’s Adirondack Forest, a Centenary Consideration, 19 ECOLOGY L.Q. 193 (1992). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading In the Adirondacks, these private interests primarily consisted of the lumber industry, which exploited the resources of the forest, utilizing clearcutting methods and modern industrial technology to harvest trees at an unprecedented rate. By the middle of the 19th century, human activity and industry had begun to shape the Adirondacks in ways never before seen, to the alarm of many. In 1857, the lawyer Stephen H. Hammond remarked on the transformation of the forest: “Had I my way, I would mark out a circle of a hundred miles in diameter, and throw around it the protecting aegis of the constitution. I would make it a forest forever. It would be a misdemeanor to chop down a tree and a felony to clear an acre within its boundaries.” At least some lawmakers in Albany shared these sentiments, and in 1872 a bill was passed creating a state park commission, which was tasked with investigating “the expediency of providing for vesting in the state the title to the timbered regions [of the Adirondacks]…and converting the same into a state park.”[6]Charles Z. Lincoln. Constitutional History of New York (1906). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library.

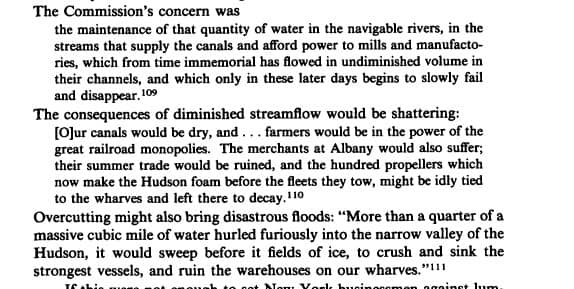

In 1873, the Commission made its report, and concluded that “the protection of a great portion of that forest [Adirondack counties] is absolutely and immediately required.”[7]Louise A. Halper, A Rich Man’s Paradise: Constitutional Preservation of New York State’s Adirondack Forest, a Centenary Consideration, 19 ECOLOGY L.Q. 193 (1992). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading The Commission’s concerns were not entirely environmental in nature, at least not in the way we understand the term in the modern era. In large part, they were driven by concerns over the economic impact of increased soil erosion, brought about by widespread deforestation, on the state’s water supply. Of particular concern was the impact of increased erosion on the state’s economically vital system of canals.

However, even in the 19th century, the recreational value of the park was recognized. In 1882, in Governor Cornell’s annual address, he remarked that the Adirondack region was one of the “most inviting resorts to invalids and tourists. Its high altitudes, pure and bracing atmosphere, perennial streams and mountain lakes in the shade of primeval forests, constitute the desirable features of a retreat designed by nature for the uses of mankind in pursuit of health or pleasure.”[8]Charles Z. Lincoln. Constitutional History of New York (1906). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. Legal scholar Louise A. Halper argues that this appeal of the Adirondacks as an idyllic retreat for the health-conscious downstate elite was instrumental in securing legal protections[9]Louise A. Halper, A Rich Man’s Paradise: Constitutional Preservation of New York State’s Adirondack Forest, a Centenary Consideration, 19 ECOLOGY L.Q. 193 (1992). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading for the Park: “self-interest was behind the successful organization to save the northern woods. The creation of the Adirondack Park and the constitutional protection of the Forest Preserve enhanced the recreational value of the great Adirondack estates of wealthy downstaters, a cross section of the social and financial elite of New York and of the country.”

Beginning in the 1880s New York reversed the century-long trend of land sales, and began buying back lands from private owners. In 1885, only three years after Cornell’s remarks, the state Forest Preserve was established. Distinct from the Adirondack and Catskills Parks—which are part of the Preserve but do not compose its entirety—the Preserve encompasses all publicly owned forested lands in the State of New York. Seven years later, subsequent legislation was passed that formally established the Adirondack Park.

Constitutional Protection

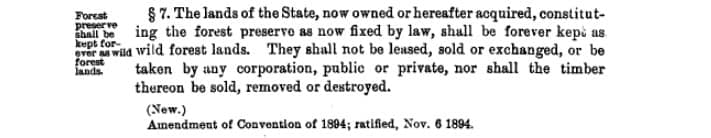

Two years after the Park’s establishment, the Adirondacks received further protection in the form of a state constitutional mandate. In Article 7 of the New York State Constitution of 1894, it was mandated that the forest preserve be “forever kept as wild forest lands.”[10]N.Y. CONST. of 1894, art. VII. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. The “forever wild” clause, as it is now known, was the first of its kind in the United States—groundbreaking constitutional law that predated the modern environmental movement by decades.

The only way for the state to make any alterations to the state Forest Preserve is by passing a constitutional amendment. Since 1941, the forever wild provision[11]N.Y. CONST. of 1938, art. XIV, § 1. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. (which is now Article 14, section 1 of the Constitution) has been amended 16 times. These amendments have been used to authorize development projects, ranging from the construction of recreational ski facilities to the I-87 highway. The most recent amendment[12]N.Y. CONST. of 1938, art. XIV, § 6. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. passed in 2017, following a popular vote, and authorized the development of bike paths and utility lines along existing highways, and established a “land bank” of 250 acres that local municipalities could use to address highway repairs and other safety concerns.

Controversies and Change Through the Present

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have seen further changes to the park, and transformations in the relationship between public and private interests in the region. Perhaps the most noteworthy change, other than those enacted by constitutional amendment, was the establishment of the Adirondack Park Agency[13]1971 N.Y. Laws. 194th Reg. Sess. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. (APA) by legislation in 1971. The APA was mandated with overseeing protected public land and supervising, and enforcing regulations, on private development within the boundaries of the Park. The establishment of the APA was met with some hostility, particularly from those that wished to further develop the park for tourism and resource extraction, and tensions at times flared to the point of violence. In 1976, there was an arson attempt on APA headquarters, and APA staffers reported violence and harassment at the hands of developers well through the 1990s.

The 1970s were also a time of renewed Indigenous activism within the Park. In 1974, Mohawk warriors occupied an abandoned girls’ camp in Moss Lake, asserting their rights to land that they claimed was fraudulently signed away in the Treaty of 1797. This initiated a three-year armed standoff between the Mohawk and New York State Police. The stand-off was resolved, after failed litigation[14]New York v. White in 4 Indian Law Reporter (1977). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. from New York State and more than 200 rounds of negotiation, in 1977 when the Mohawk agreed to relocate to a plot of land in the northeast corner of the park. The community of Ganienkeh, near the town of Altona, remains autonomous Indigenous territory through the present day, and stands out as one of the most successful reoccupations of Indigenous land in North America.

Following the often acrimonious relations of the late twentieth century, the first decades of the twenty-first century have given rise to what many see as a growing spirit of cooperation and understanding in the Adirondacks, seemingly in the face of the trends of political polarization throughout the country as a whole. Recent years have seen the establishment of local organizations, such as the Adirondacks Common Ground Alliance, which seek to foster dialogue between business owners, residents, environmental preservationists, and state officials. The wilderness status of the Adirondacks continues to be contested, in the courts[15]Todd Thomas, Adirondack Land Use under the “Forever Wild” Clause after Protect!, 29 BUFF. ENV’t L.J. 43 (2021-2022). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and elsewhere, but the important work of balancing the needs of human development with natural preservation continues.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more the environment, Indigenous land rights, and conservation, check out these posts on the HeinOnline blog:

- It’s Getting Hot in Here: How Climate Change Impacts Labor & Water Rights

- Arizona v. Navajo Nation: A Conflict of Water Rights

- Secrets of the Serial Set: Yellowstone National Park

- The Movement to Free Niagara

If you want to make sure not to miss any more posts like these, hit the subscribe button below, to have future posts delivered directly to your Inbox

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Frederick Webb Hodge. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico (1912). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | E.B. O’Callaghan. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York; Procured in Holland, England and France (1857). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑3 | Treaty with the Six Nations, . 7 Stat. 44 (1794). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s United States Statutes at Large collection. |

| ↑4 | Mohawks: Relinquishment by the Mohawks of all claims to land in the State of New York, 7 Stat. 61 (1797). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s United States Statutes at Large collection. |

| ↑5, ↑7 | Louise A. Halper, A Rich Man’s Paradise: Constitutional Preservation of New York State’s Adirondack Forest, a Centenary Consideration, 19 ECOLOGY L.Q. 193 (1992). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6, ↑8 | Charles Z. Lincoln. Constitutional History of New York (1906). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑9 | Louise A. Halper, A Rich Man’s Paradise: Constitutional Preservation of New York State’s Adirondack Forest, a Centenary Consideration, 19 ECOLOGY L.Q. 193 (1992). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑10 | N.Y. CONST. of 1894, art. VII. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑11 | N.Y. CONST. of 1938, art. XIV, § 1. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑12 | N.Y. CONST. of 1938, art. XIV, § 6. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s State Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑13 | 1971 N.Y. Laws. 194th Reg. Sess. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s New York Legal Research Library. |

| ↑14 | New York v. White in 4 Indian Law Reporter (1977). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas collection. |

| ↑15 | Todd Thomas, Adirondack Land Use under the “Forever Wild” Clause after Protect!, 29 BUFF. ENV’t L.J. 43 (2021-2022). This article can found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |