With deadly heatwaves blasting regions around the globe, 2023 is on track to become the hottest year on record. In the United States, this summer has featured a number of unusual weather phenomena—torrential flooding in Vermont and the Hudson Valley, dense wildfire smoke that tanked air quality in the Northeast and Midwest, and a 31-day streak of 110+ degree temperatures in Phoenix, to name just a few. The rising temperatures worldwide are largely thanks to climate change—and with the heat not going away any time soon, adaptations and considerations must be made to ensure survival.

In this post, we are going to take a look at two of HeinOnline’s newest databases, Labor and Employment: The American Worker and Water Rights & Resources, to show the effects that climate change have on labor and water rights in America.

Laboring in the Heat

At the Federal Level

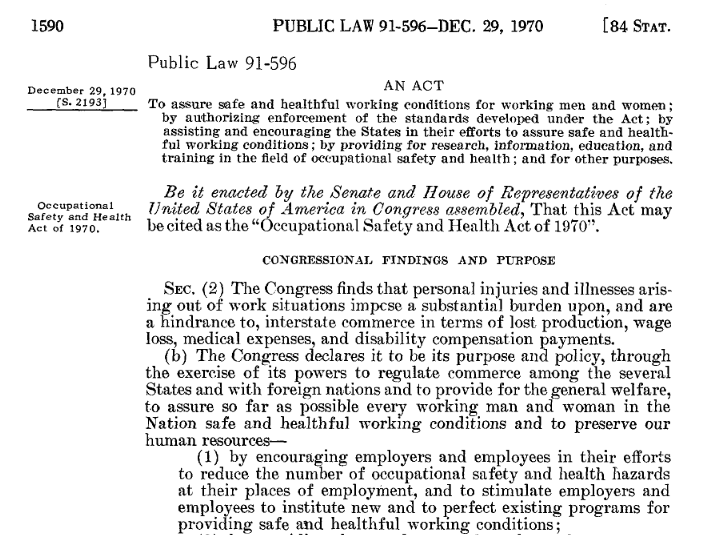

Currently, there are no federal laws that explicitly protect workers in extreme heat conditions. In 1972, the Nixon administration was the first to propose heat protection standards at the federal level, but they never passed. Currently, the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970[1]To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women, by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; … Continue reading requires employers to provide “safe and healthful working conditions”—but this does not specifically require employers to protect workers from heat. President Biden has asked the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to develop protocol for Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Settings,[2]1 1 (August 10, 2022) Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Regulation of Employee Exposure to Heat. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. which would require employers to protect workers from extreme heat just like they are required to protect workers from other occupational hazards. However, the process to pass protocol is slow.

In 2018, 49 workplace fatalities[3]Stephanie Milner, Hot Topic Getting Hotter: Employer Heat Injury Liability Mitigation in the Age of Climate Change, 36 A.B.A. J. LAB. & EMP. L. 177 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading were reported due to heat exposure. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that almost 40 workers die each year due to heat-related conditions. However, this number is likely inaccurate as death certificates often don’t take into account the role of heat[4]1 102 (2019) From the Fields to the Factories: Preventing Workplace Injury and Death from Excessive Heat: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth … Continue reading in causing fatal conditions such as respiratory failure and heart attacks. Some of the most vulnerable workers are those in agriculture, warehouses, package delivery, construction, and manufacturing[5]Stephanie Milner, Hot Topic Getting Hotter: Employer Heat Injury Liability Mitigation in the Age of Climate Change, 36 A.B.A. J. LAB. & EMP. L. 177 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading—where employees perform heavy manual labor either outdoors or in non-air-conditioned indoor settings. Many of the nation’s agricultural workers are undocumented immigrants, who risk deportation[6]1 102 (2019) From the Fields to the Factories: Preventing Workplace Injury and Death from Excessive Heat: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth … Continue reading if they complain about their working conditions or report workplace injuries. UPS trucks aren’t air-conditioned[7]H. Rept. 117-547 20 (2022-11-07)

ASUNCION VALDIVIA HEAT ILLNESS AND FATALITY PREVENTION ACT OF 2022. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. or insulated, meaning drivers swelter on hot days—the Teamsters have negotiated with UPS to get air-conditioned new vehicles beginning in 2024.

Many other countries require employers to offer protective measures for extreme heat, including China, Spain, Costa Rica, and even Qatar, which recently implemented limits on outdoor work in the heat after many laborers died in sweltering conditions while building infrastructure for the World Cup.

At the State Level

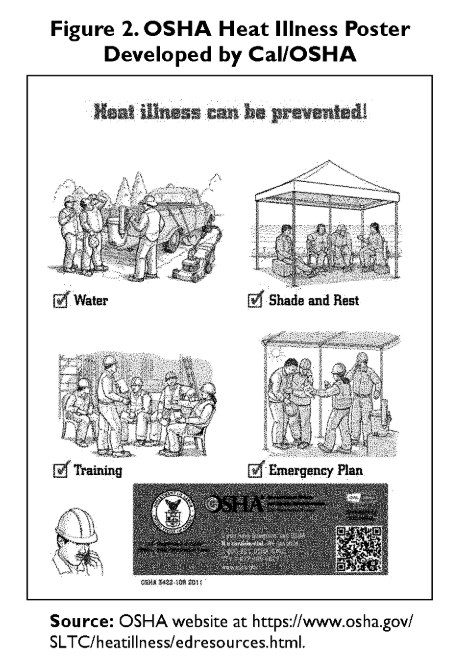

Currently, the only states with permanent laws that require employers to protect workers from the heat are California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, and Minnesota. For example, California implemented heat protection protocol[8]6 (June 3, 2016) OSHA State Plans: In Brief, with Examples from California and Arizona This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. that kicks in when temperatures reach 85°F after several workers died during a heat wave. Last year, Oregon OSHA published a Heat Illness Prevention standard that applies to outdoor and indoor environments when the heat index reaches 80°F. In 2008, Washington adopted outdoor heat exposure standards to protect workers in outdoor environments when temperatures reach 100°F—these rules were updated this year. Colorado passed a law[9]2021 vol. 2 2179 (2021) Chapter 337. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. in 2022 protecting agricultural employees from heat-related stress illnesses. Minnesota’s heat-related employee protections only apply to indoor workplaces.[10]86 Fed. Reg. 59316 (2021), Wednesday, October 27, 2021, pages 59279 – 59602. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. Other states have released emergency protections for employees or are requiring state administrators to create rules regarding heat safety on the job.

However, these efforts in other states have encountered resistance. A stalled bill in New York would require employers to protect outdoor workers and provide air conditioning in certain environments. A rule in Nevada to require water, shade, and rest breaks once the temperature reaches 105°F never passed. Florida has also failed to pass bills protecting workers from heat-related conditions—however, Miami-Dade County is pushing to protect construction and agricultural workers. And most recently, Texas governor Greg Abbott passed a law that eliminates rest and water breaks for construction workers in Austin and Dallas, despite a record-breaking heat wave this summer.

Water Rights Drying Up

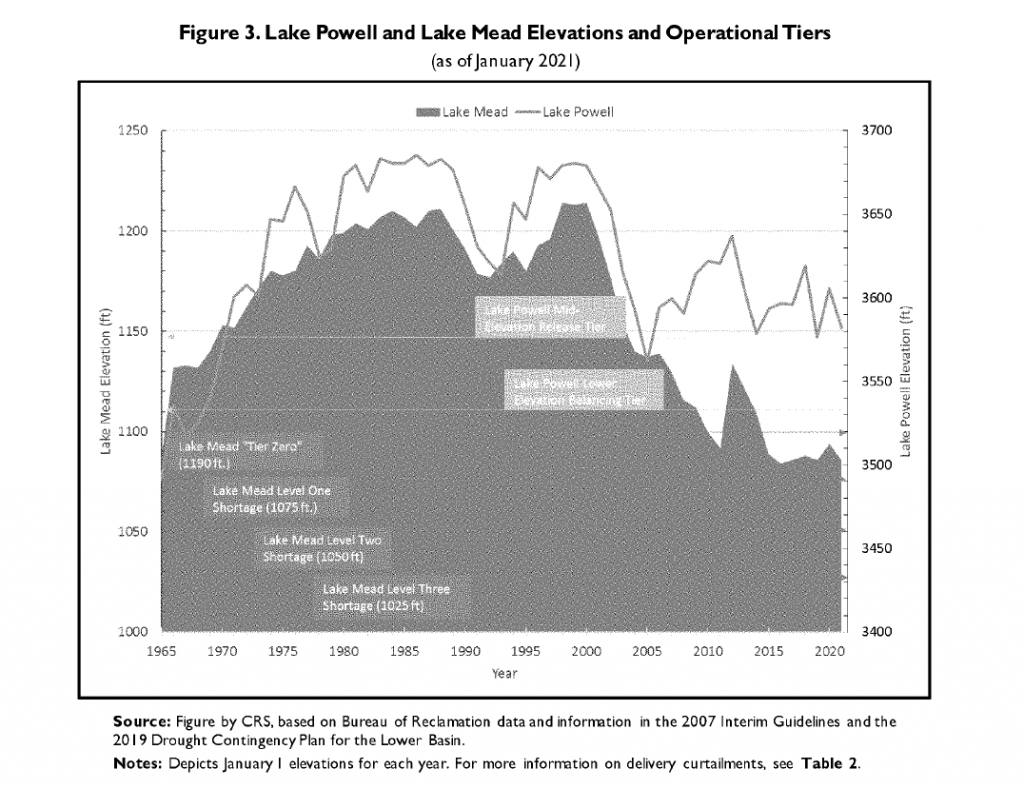

The Colorado River serves as the main source of water for seven states in the Southwest: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming (Upper Basin) and Arizona, California, and Nevada (Lower Basin). Additionally, it provides water to parts of Mexico and two dozen Indigenous tribes—approximately 40 million people in total. However, with the West in a megadrought that began in 2000, the River and its reservoirs have been drying up—in April 2021, Lake Mead, which is the Colorado River’s largest reservoir, was only 38% full. By February 2022, Lake Mead and Lake Powell were at their lowest ever recorded levels. Even in 2019, water had to be moved from other reservoirs to Lake Powell as part of the Upper Basin and Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plans.[11]1 21 (2021) Status and Management of Drought in the Western United States: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Water and Power of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, U.S. Senate, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, First Session. This … Continue reading

The amount of water that each of the seven states is allotted was determined in the 1922 Colorado River Compact[12]Ray Lyman; Ely Wilbur, Northcutt. Hoover Dam Power and Water Contracts and Related Data: With Introductory Notes (1933). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and Water Rights & Resources … Continue reading following an abnormally wet period, which means that the allotments were based on significantly overestimated river flow. This law, which was ratified by the states and Congress, will expire in 2026, but until then, states have already had to agree to use less water.

A study published in Nature Climate Change discovered that 42% of soil moisture loss from 2000 to 2021 was due to climate change—warmer temperatures cause evaporation, which means soil now requires more water to support agriculture. Additionally, snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, which provides around 30% of California’s water supply,[13]1 10 (March 16, 2023) Central Valley Project: Issues and Legislation. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. has been creating less runoff.[14]1 20 (2021) Status and Management of Drought in the Western United States: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Water and Power of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, U.S. Senate, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, First Session. This … Continue reading

“First in Time, First in Right”

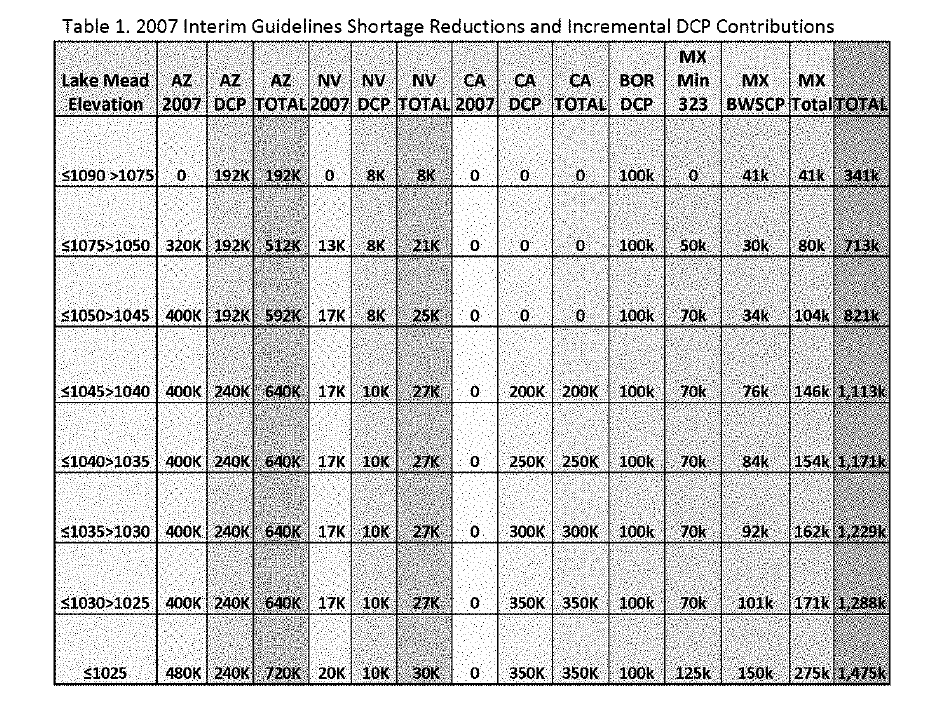

Water rights in the United States work on a “first in time, first in right”[15]Rebecca Glenn, Unrealized Federal Indian Water Rights on the Colorado River: An Opportunity for Equity and Conservation, 25 U. DENV. WATER L. REV. 287 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal … Continue reading basis, which means that states that first utilized the water resource receive first priority. In the case of the Colorado River, particularly the Lower Basin, this means that California receives first priority, while Arizona and Nevada are the first to receive cutbacks. In 2021, federal officials for the first time declared a water shortage,[16]1 12 (May 5, 2023) Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role at Lake Mead. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. resulting in water cuts to Arizona, Nevada, and parts of Mexico near the border.

The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation had been prepared to force states to make water cuts, but this May, the Lower Basin states agreed to propose a plan that would reduce Colorado River use and conserve 3 million acre-feet of water by 2026,[17]1 29 (May 23, 2023) Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. with federal funding to be provided to cities and tribes affected by the cuts. The cuts aren’t as significant as they might have been had this past winter not been a particularly wet one. The plan is now under review by the Bureau of Reclamation. However, additional cuts are likely to be needed once the Colorado River Compact expires in 2026 and water allotments are renegotiated.

Tribal Water Rights

It’s not just the states that rely on access to water from the Colorado River. Several Indigenous tribes across the Southwest depend on this water for their livelihood, including the Chemehuevl, Hopi, Mohave, and Navajo, also known as the Colorado River Indian Tribes. Historically, many of these rights have not been recognized. Just this summer, in the case Arizona v. Navajo Nation,[18]21-1484 U.S. Reports 1 (2023) Arizona et al. v. Navajo Nation et al. This Slip Opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. the Supreme Court ruled that it was not the federal government’s responsibility to ensure the tribe can access the water they need from the Colorado River. However, Congress has enacted several Indigenous water rights settlements in the past decade, including the Hualapai Tribe Water Rights Settlement Act of 2022.[19]Public Law 117-349, 117 P.L. United States 136 STAT. 6225 (2022). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database.

Explore Labor and Water Rights with Two of HeinOnline’s Newest Databases

Work labor rights into your research with HeinOnline’s Labor and Employment: The American Worker, a collection of more than 10,000 titles that cover the plight and successes of America’s working class. Explore topics such as employment benefits, immigrant workers & agriculture, labor unions, occupational illness & dangers, workplace protections, and much more—you’ll find titles that explore how heat impacts laborers, what’s being done (and not done) to protect workers from climate change, and more.

Additionally, dive into Water Rights & Resources, a highly editorialized and affordable database for understanding state and federal laws governing water. Learn all about the unique water rights issues that span from the Eastern Seaboard to the Great Lakes and across the arid West, with titles that tackle issues like riparian rights, tribal water rights, water conservation, and more. Topics related to climate change include drought and water scarcity, flood and flood control, water rights and claims, and much more.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women, by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health, and for other purposes., Public Law 91-596, 91 Congress. 84 Stat. 1590 (1970). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 1 1 (August 10, 2022) Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Regulation of Employee Exposure to Heat. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

| ↑3, ↑5 | Stephanie Milner, Hot Topic Getting Hotter: Employer Heat Injury Liability Mitigation in the Age of Climate Change, 36 A.B.A. J. LAB. & EMP. L. 177 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

| ↑4, ↑6 | 1 102 (2019) From the Fields to the Factories: Preventing Workplace Injury and Death from Excessive Heat: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixteenth Congress, First Session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

| ↑7 | H. Rept. 117-547 20 (2022-11-07) ASUNCION VALDIVIA HEAT ILLNESS AND FATALITY PREVENTION ACT OF 2022. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

| ↑8 | 6 (June 3, 2016) OSHA State Plans: In Brief, with Examples from California and Arizona This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Labor and Employment: The American Worker databases. |

| ↑9 | 2021 vol. 2 2179 (2021) Chapter 337. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑10 | 86 Fed. Reg. 59316 (2021), Wednesday, October 27, 2021, pages 59279 – 59602. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |

| ↑11 | 1 21 (2021) Status and Management of Drought in the Western United States: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Water and Power of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, U.S. Senate, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, First Session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑12 | Ray Lyman; Ely Wilbur, Northcutt. Hoover Dam Power and Water Contracts and Related Data: With Introductory Notes (1933). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑13 | 1 10 (March 16, 2023) Central Valley Project: Issues and Legislation. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑14 | 1 20 (2021) Status and Management of Drought in the Western United States: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Water and Power of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, U.S. Senate, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, First Session. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑15 | Rebecca Glenn, Unrealized Federal Indian Water Rights on the Colorado River: An Opportunity for Equity and Conservation, 25 U. DENV. WATER L. REV. 287 (2022). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑16 | 1 12 (May 5, 2023) Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role at Lake Mead. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑17 | 1 29 (May 23, 2023) Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents and Water Rights & Resources databases. |

| ↑18 | 21-1484 U.S. Reports 1 (2023) Arizona et al. v. Navajo Nation et al. This Slip Opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑19 | Public Law 117-349, 117 P.L. United States 136 STAT. 6225 (2022). This statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |