Barbenheimer defined Summer 2023 and even the HeinOnline Blog couldn’t escape the movie event of the year. We gave Barbie the HeinOnline treatment last month, and so this month it’s Oppenheimer’s turn, with a special focus on J. Robert Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing in 1954. Need an atomic history refresher? We previously unlocked the Los Alamos Laboratory and the Manhattan Project in this post using the Serial Set.

The following HeinOnline databases will play a starring role as we probe our current pop culture moment:

Before we begin, spoiler(?) warning, as this post will be discussing historical events that play important dramatic roles in the movie.

Lewis Strauss

Lewis Strauss, played by Robert Downey Jr. in the film, is a central figure to Oppenheimer’s story, but one whom many audience members may have never heard of before. During World War I, Strauss served as Herbert Hoover’s private secretary while the future president ran the Commission for Relief in Belgium[1]John Hamill. Strange Career of Mr. Hoover under Two Flags (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. and the U.S. Food Administration,[2]Jay Cooke, Work of the Federal Food Administration, The, 78 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 175 (1918). This essay is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. which was responsible for domestic food rationing.

After the war, Strauss landed a job at the investment bank Kuhn, Loeb & Co. through his connections with Hoover. The gig made him a wealthy man. During World War II, Strauss joined the Navy Reserve as a commissioned officer, eventually being promoted to rear admiral in 1945. He helped establish the Office of Naval Research and served as the Navy’s representative on the Interdepartmental Committee on Atomic Research. Strauss ultimately influenced the final decision to choose Bikini Atoll[3]Zohl de Ishtar, Poisoned Lives, Contaminated Lands: Marshall Islanders Are Paying a High Price for the United States Nuclear Arsenal, 2 Seattle J. Soc. Just. 287 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. as the site for Operation Crossroads,[4]Operation Crossroads: Personnel Radiation Exposure Estimates Should Be Improved (1985). This report is found in HeinOnline’s GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions. the first post-war nuclear weapons tests.

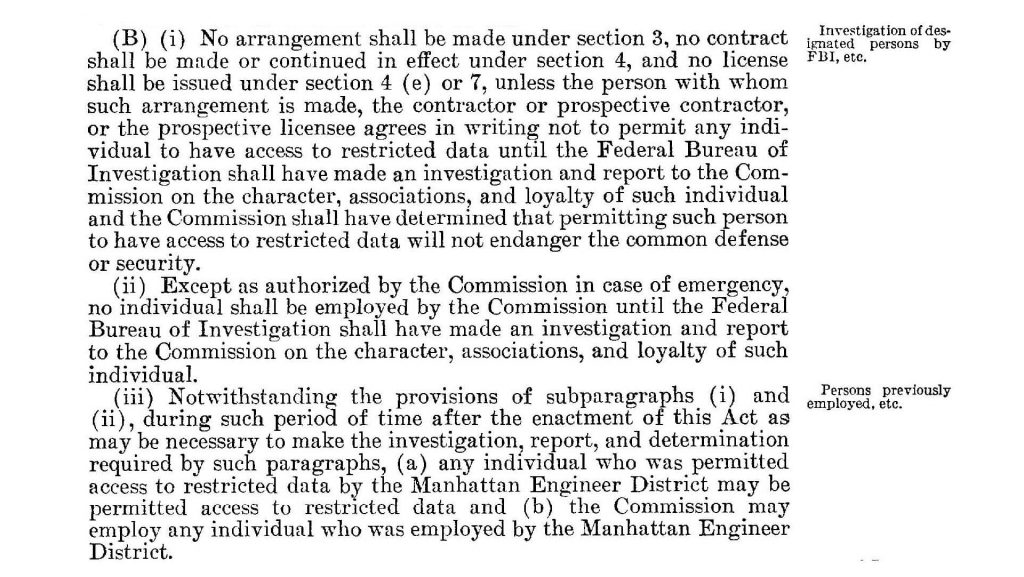

In 1947, atomic research was transferred from the Army to the new civilian-led Atomic Energy Commission.[5]Dowlen Shelton, The Atomic Energy Commission, 5 Sw. L.J. 193 (1951). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The Atomic Energy Commission was created in 1946 by the Atomic Energy Act.[6]60 Stat. 755 (1946). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. President Truman named Strauss one of the first Commissioners. As a Commissioner, Strauss advocated for absolute secrecy over American atomic information, wanting to exclude even Britain,[7]Raymond Dawson & Richard Rosecrance, Theory and Reality in the Anglo-American Alliance, 19 WORLD POL. 21 (1966). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. America’s closest ally, from information sharing, for fear that the Soviets would develop nuclear weapons. After the Soviet Union tested their first atomic bomb in 1949, Strauss adamantly argued for the U.S. to develop the more powerful hydrogen bomb,[8]Alfred Goldberg, Editor. History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (1984-2015). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. or “super bomb.” Among opponents of the hydrogen bomb was J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was now serving as chairman of the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission.

![We believe a super bomb should never be produced. Mankind would be far better off not to have a demonstration of the feasibility of such a weapon until the present climate of world opinion changes. It is by no means certain that the weapon can be developed at all and by no means certain that the Russians will produce one within a decade. To the argument that the Russians may succeed in developing this weapon, we would reply that our undertaking it will not prove a deterrent to them. Should they use the weapon against us, reprisals by our large stock of atomic bombs would be comparably effective to the use of a super. In determining not to proceed to develop the super bomb, we see a unique opportunity of providing by example some limitations on the totality of war and thus of limiting the fear and arousing the hope of mankind. [Signed] James B. Conant, Hartley Rowe, Cyril Stanley Smith, L[ee] A. DuBridge, Oliver E. Buckley, J. R[obert] Oppenheimer](https://home.heinonline.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/1949volINationalSecurityA-1024x783.jpg)

Strauss already had bad blood with Oppenheimer thanks to a humiliating exchange in 1949. Strauss, a physics aficionado, had been arguing against America’s export of isotopes, claiming they could be used to produce nuclear weapons. Replying to Strauss’ assertion, Oppenheimer replied, “My own rating of the importance of isotopes in this broad sense is that they are far less important than electronic devices, but far more than, let us say, vitamins, somewhere in between.”[9]Investigation into the United States Atomic Energy Project: Hearing before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, Congress of the United States, Eighty-First Congress, First Session, Part 7 (1949). This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s … Continue reading The quip earned raucous laughter, and Strauss never forgot the insult.

On the question of the hydrogen bomb, the Atomic Energy Commission demurred, voting against the bomb’s development but sending the matter to President Truman to make the final decision. In the White House, the bomb’s development was again championed by Strauss, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the State Department, and ultimately approved by President Truman in January 1950. Strauss’ term on the Atomic Energy Commission came to an end that year, but he returned as chairman under President Eisenhower in 1953.

J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Atomic Energy Commission

When the Atomic Energy Act was passed in 1946, it included a provision that any Manhattan Project employee who had received a wartime security clearance needed to be re-certified[10]60 Stat. 755 (1946). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. in peacetime to keep their clearance. Accordingly, Oppenheimer was investigated by the FBI and was unanimously given a Q clearance, the highest level of security clearance, by the Atomic Energy Commission on August 11, 1947.

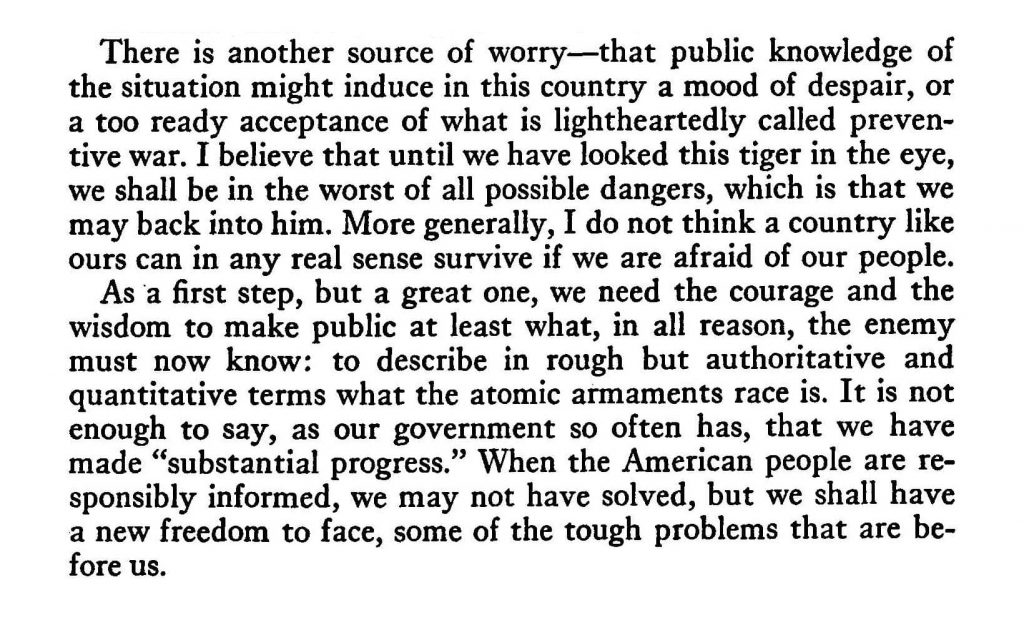

In addition to his advisory role to the Atomic Energy Commission, Oppenheimer served on a number of government panels, including chairing the Panel of Consultants on Disarmament in 1952 for the State Department. Ahead of the first hydrogen bomb test, the Panel issued a deeply skeptical report[11]Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954, Dwight D. Eisenhower vol. II, National Security Affairs. This volume is found in HeinOnline’s Foreign Relations of the United States. on thermonuclear weapons and the certain arms race it would start with the Soviet Union. While the Panel ultimately failed to stop the hydrogen bomb’s deployment, it did succeed in convincing the Eisenhower administration to be frank with the American public about the perils of nuclear war.[12]Alfred Goldberg, Editor. History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (1984-2015). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. In July 1953, Oppenheimer published an article[13]J. Robert Oppenheimer, Atomic Weapons and American Policy, 31 Foreign Aff. 525 (1953). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. in Foreign Affairs[14]The full archive of this journal can be accessed in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. arguing his vision for U.S. nuclear policy.

Obviously, Oppenheimer and Strauss were at odds about the world’s direction with regards to nuclear weapons. On November 7, 1953, former executive director of the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy William Liscum Borden—with a lot of behind the scenes help from Strauss—accused Oppenheimer of being a Soviet Agent. At Strauss’ urging, President Eisenhower put a “blank wall”[15]John W. Caughey. Their Majesties the Mob (1960). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice. between Oppenheimer and atomic secrets, and his security clearance was suspended. The following spring, the Atomic Energy Commission held hearings on whether Oppenheimer’s security clearance should be reinstated.

Oppenheimer’s Security Clearance Hearing

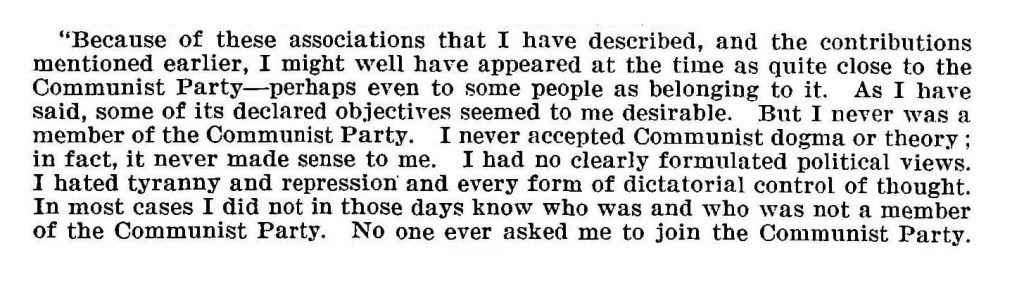

The Atomic Energy Commission’s four week investigation into Oppenheimer started on April 12, 1954.[16]In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: Transcript of Hearing before Personnel Security Board, Washington D.C., April 12, 1954, through May 6, 1954 (1954). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. At issue were allegations of Oppenheimer’s Communist sympathies and whether he was loyal to the United States. None of this was new. Oppenheimer had been under surveillance by the FBI since 1941[17]Barton J. Bernstein, The Oppenheimer Loyalty-Security Case Reconsidered, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 1383 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and his Communist sympathies and associations were well-documented.

But the 1954 charges came at the height of McCarthyism[18]Barton J. Bernstein, The Oppenheimer Loyalty-Security Case Reconsidered, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 1383 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and in a post-war world whose atomic politics Oppenheimer was now on the wrong side of. In this environment, old accusations had new meaning. In 1949, the House Un-American Activities Committee interrogated Oppenheimer in a closed session as part of a sweeping set of hearings into a Communist cell at Berkeley’s radiation laboratory during the same time as the Manhattan Project.

The Berkeley fiasco, better known as the Chevalier Incident,[19]Barton J. Bernstein, The Oppenheimer Loyalty-Security Case Reconsidered, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 1383 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. centered around Haakon Chevalier, an associate professor of French at Berkeley and a friend of Oppenheimer’s. In 1943, Chevalier told Oppenheimer that he had a channel to the Soviet Union through a scientist named George Eltenton, implying a way for Oppenheimer to share atomic secrets. Eight months later, Oppenheimer told the Army about the conversation, but did not identify Chevalier. He later named Chevalier to Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves, Manhattan Project director. The story resurfaced again in 1946 when Oppenheimer was questioned by the FBI about the incident. Damningly for Oppenheimer, his 1946 version of events differed from the original 1943 account. The Commission latched onto this discrepancy in 1954.

Further compromising Oppenheimer were his Communist associations. His brother, sister-in-law, and wife were all Communist Party members, and Oppenheimer had a serious affair with Communist member Jean Tatlock. On his own, Oppenheimer admitted financial involvement with Communist front organizations in the 1930s. Oppenheimer acknowledged to the Committee that, although he was friends with many Communist and “leftwing” people, he was not a Communist.

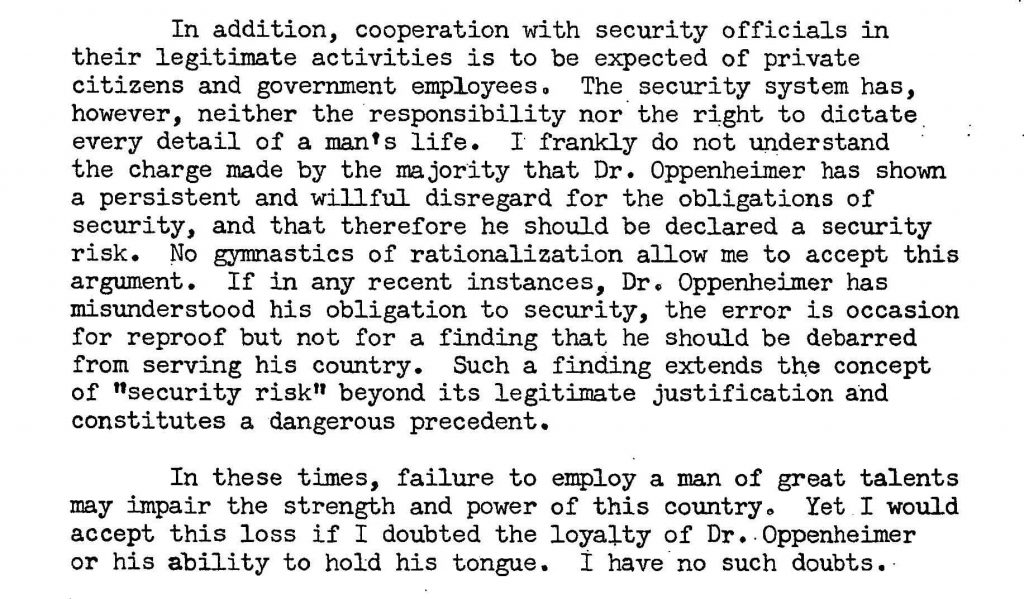

Despite testimony from highly respected scientists and military personnel, the Atomic Energy Commission voted 2–1 to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance. Henry DeWolf Smyth, a former consultant on the Manhattan Project who wrote its official history,[20]Henry DeWolf Smyth. Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: The Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal … Continue reading was the only Commissioner to vote “no.” He filed a dissent against the Commission’s decision, writing:

Oppenheimer and Strauss, In the End

J. Robert Oppenheimer never again worked for the federal government after losing his security clearance. An academic exile, he spent a great deal of time at his home in the U.S. Virgin Islands, occasionally lecturing on moral quandaries scientists face through their work. President John F. Kennedy conferred the 1963 Enrico Fermi Award onto Oppenheimer,[21]Lyndon B. Johnson, Remarks upon Presenting the Fermi Award to Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer – December 2, 1963, 1963 Pub. Papers 17 (1963). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. one of the nation’s most prestigious scientific honors. Kennedy was assassinated before he could present the award to Oppenheimer; President Johnson did the honors instead, one week after Kennedy’s death. Oppenheimer died on February 18, 1967 of throat cancer, at the age of 62. Two days after his death, Senator J. William Fulbright spoke of Oppenheimer on the Senate floor, saying, “Let us remember not only what his special genius did for us; let us also remember what we did to him.”[22]113 Cong. Rec. 3903 (1967). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents.

Lewis Strauss is best remembered today for orchestrating Oppenheimer’s public downfall. He did not return to chair the Atomic Energy Commission after 1958 and instead was nominated by President Eisenhower to be Secretary of Commerce. The U.S. Senate rejected Strauss’ nomination, 49 to 46.[23]D. F. Fleming. Cold War and Its Origins, 1917-1960 (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. He involuntarily retired from public life and died on January 21, 1974.

The Atomic Energy Commission was dissolved in 1975. Its duties were later rolled into the new Department of Energy. On December 16, 2022, the Department of Energy vacated the Atomic Energy Commission’s decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance.

Put Some Pop (Culture) in Your Research

We all know that impulse to Google for more information after consuming a great movie or tv show, or even after hearing a bit of the latest celebrity gossip. Why not incorporate the primary sources into your post-viewing research? Any time you see that “based on a true story” tagline, start your research in HeinOnline to go behind the scenes with primary sources and authoritative secondary sources.

Dare to doubt how relevant HeinOnline can be in this endeavor? Check out the Pop Culture tag in the HeinOnline blog for examples in action from HeinOnline Bloggers. Some of our favorite examples include:

- Everything or Nothing: The Copyright History of James Bond

- Overprotected: A Timeline of Britney Spears’s Conservatorship and the #FreeBritney Movement

- Uneasy Lies the Head That Wears ‘The Crown’

- Offsides: The Trials of Deshaun Watson

Be sure to subscribe to get more great posts like this delivered straight to your inbox.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | John Hamill. Strange Career of Mr. Hoover under Two Flags (1931). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jay Cooke, Work of the Federal Food Administration, The, 78 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. & Soc. Sci. 175 (1918). This essay is found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated. |

| ↑3 | Zohl de Ishtar, Poisoned Lives, Contaminated Lands: Marshall Islanders Are Paying a High Price for the United States Nuclear Arsenal, 2 Seattle J. Soc. Just. 287 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | Operation Crossroads: Personnel Radiation Exposure Estimates Should Be Improved (1985). This report is found in HeinOnline’s GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions. |

| ↑5 | Dowlen Shelton, The Atomic Energy Commission, 5 Sw. L.J. 193 (1951). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑6, ↑10 | 60 Stat. 755 (1946). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑7 | Raymond Dawson & Richard Rosecrance, Theory and Reality in the Anglo-American Alliance, 19 WORLD POL. 21 (1966). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑8, ↑12 | Alfred Goldberg, Editor. History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (1984-2015). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |

| ↑9 | Investigation into the United States Atomic Energy Project: Hearing before the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, Congress of the United States, Eighty-First Congress, First Session, Part 7 (1949). This hearing is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑11 | Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954, Dwight D. Eisenhower vol. II, National Security Affairs. This volume is found in HeinOnline’s Foreign Relations of the United States. |

| ↑13 | J. Robert Oppenheimer, Atomic Weapons and American Policy, 31 Foreign Aff. 525 (1953). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14 | The full archive of this journal can be accessed in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15 | John W. Caughey. Their Majesties the Mob (1960). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice. |

| ↑16 | In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: Transcript of Hearing before Personnel Security Board, Washington D.C., April 12, 1954, through May 6, 1954 (1954). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑17, ↑18, ↑19 | Barton J. Bernstein, The Oppenheimer Loyalty-Security Case Reconsidered, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 1383 (1990). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑20 | Henry DeWolf Smyth. Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: The Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940-1945 (1946). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics. |

| ↑21 | Lyndon B. Johnson, Remarks upon Presenting the Fermi Award to Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer – December 2, 1963, 1963 Pub. Papers 17 (1963). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Presidential Library. |

| ↑22 | 113 Cong. Rec. 3903 (1967). This document is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents. |

| ↑23 | D. F. Fleming. Cold War and Its Origins, 1917-1960 (1961). This book is found in HeinOnline’s Military and Government. |