November is National Native American Heritage Month, honoring the culture, history, and achievements of America’s Indigenous peoples. It’s also a time to recognize the suffering that Indigenous peoples have endured for centuries as the result of European settlement and expansion. At many points throughout U.S. history, native peoples were treated as subhuman and were not provided with basic human rights by federal and state governments. Various court cases have revolved around the rights that Indigenous peoples do and do not have, and the jurisdiction that state and federal governments have over native peoples and their land. In this post, we’ll use HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library and Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database to explore 5 influential court cases that impacted Indigenous peoples’ rights and livelihood.

And in honor of National Native American Heritage Month, we’re offering a 20% discount on the first-year subscription price of Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law through November 30, 2024. Keep reading to learn more about this comprehensive resource.

Case 1: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831)

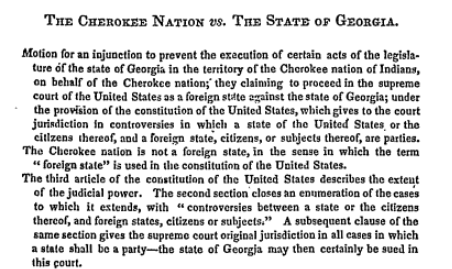

Throughout the 1820s, the state of Georgia passed a series of laws declaring that Cherokee tribal territory could be broken up and distributed to white settlers, and that any Cherokee who did not comply with these laws would be punished. The Cherokee Nation, however, claimed that these laws were unconstitutional based on provisions of treaties between the tribe and the U.S. government, which provided sovereignty and federal protection to the Cherokee Nation. Additionally, the Cherokee Nation argued that it was “a foreign state, not owing allegiance to the United States, nor to any State of this union, nor to any prince, potentate or State, other than their own.”[1]Landmark Indian Law Cases (2002). Landmark Indian Law Cases. Buffalo, N.Y., William S. Hein & Co., Inc. This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. Under Article III of the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court has jurisdiction “between a State or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens, or subjects,”[2]Louis; Guttmann, Allen, Editors Filler. Removal of the Cherokee Nation: Manifest Destiny or National Dishonor (1962). This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. and therefore, if the Cherokee Nation was a foreign state, the U.S. Supreme Court would be able to intervene and rule on the constitutionality of the Georgia laws.

However, in the decision, Chief Justice John Marshall defined the Cherokee Nation as a “domestic dependent nation.” He also wrote that “the relationship of the tribes to the United States resembles that of a ‘ward to its guardian’.”[3]Rory Flay, A Silent Epidemic: Revisiting the 2013 Reauthorization of the Violence against Women Act to Better Protect American Indian and Alaska Native Women, 5 AM. INDIAN L.J. 230 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law … Continue reading The Court ruled that it could not hear the case, and the Georgia laws were allowed to enforce the evacuation of the Cherokee from their lands.

Case 2: Worcester v. Georgia (1832)

One year after Cherokee Nation v. Georgia,[4]30 (5 Peters) U.S. 1 (1831) Cherokee Nation vs. the State of Georgia, The. This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library that decision was effectively reversed. Samuel A. Worcester and several other white missionaries were living in Cherokee Nation territory in Georgia and encouraging the tribe to resist the laws the state was imposing on them. When the state caught wind of this, it passed a law[5]Oliver H. Prince, Compiler. Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia Containing All Statutes and the Substance of All Resolutions of a General and Public Nature (2). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. forbidding non-Native Americans from living on Cherokee land without a license and without pledging an oath of loyalty to the state. Worcester and several others were subsequently arrested. He appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court with a similar argument to the one used in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia—that state laws did not apply to Cherokee Nation. Additionally, Worcester argued that the law violated the U.S. Constitution, which only grants U.S. Congress the authority to regulate commerce with Native Americans, as well as forbids states from passing laws that go against treaties between Indigenous tribes and U.S. government.

The Supreme Court agreed with Worcester. In a 5-1 decision, the Court reversed its decision in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia just one year before. It ruled that Georgia state laws impacting the Cherokee Nation were unconstitutional.

The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory…in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves, or in conformity with treaties and with the acts of Congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation, is, by our Constitution and laws, vested in the Government of the United States.

However, President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce[6]Chantelle van Wiltenburg, “The Center Cannot Hold”: Nation and Narration in American Indian Law, 47 AM. INDIAN L. REV. 127 (2023). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. the Worcester v. Georgia decision. The U.S. Government began to force the Cherokee from their lands, in a diaspora that became part of what is known as the Trail of Tears,[7]W. R. L. Smith. Story of the Cherokees (1928). This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. along which approximately 6,000 Cherokee perished.

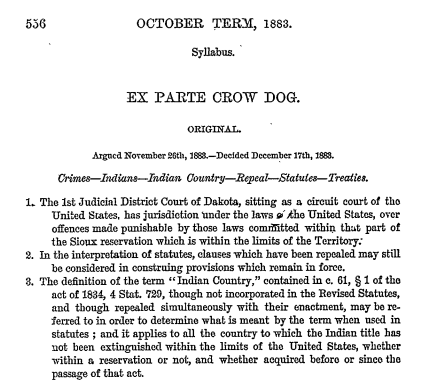

Case 3: Ex Parte Crow Dog (1883)

On August 5, 1881, Crow Dog, a member of the Brulé band of the Lakota Sioux tribe, shot and killed Lakota chief Spotted Tail on the Great Sioux Reservation, located in what is today South Dakota. In accordance with Sioux law, as punishment Crow Dog paid restitution to Spotted Tail’s family.[8]Margaret Campbell Haynes; June L. Melvin. Tribal and State Court Reciprocity in the Establishment and Enforcement of Child Support (1991). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. However, the Dakota Territory government then proceeded to arrest Crow Dog and prosecuted him for murder in federal court, where he was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Crow Dog petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, claiming that the federal government did not have jurisdiction over crimes occurring between Indigenous peoples in Indigenous territory based on the General Crimes Act of 1834.[9]Uriah, et al., Editors Barnes. Barnes’ Federal Code, Containing All Federal Statutes of General and Public Nature Now in Force (1919). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. Plus, he had already been tried and punished by tribal court. However, the Dakota Territory argued that an 1868 treaty with the Sioux tribe,[10]Sioux Indians: Treaty between the United States of America and different tribes of Sioux Indians, 15 Stat. 635 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law and U.S. Treaties and … Continue reading which stated that criminals were required to be surrendered to the United States, superseded and nullified the 1834 act.

The Supreme Court, however, disagreed. In a decision authored by Justice Stanley Matthews, the Court voted unanimously in Crow Dog’s favor, and he was released.

However, in response to the case, two years later Congress passed the Major Crimes Act.[11]To revise, codify, and enact into positive law, Title 18 of the United States Code, entitled ‘Crimes and Criminal Procedure’., Public Law 80-772 / Chapter 645, 80 Congress. 62 Stat. 683 (1949) (1948). This act can be found in … Continue reading This act established a list of crimes that would come under federal jurisdiction if committed by a Indigenous person against another Indigenous person on tribal land. This list initially included seven crimes: murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intention to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny. Eight more crimes were eventually added to the list.

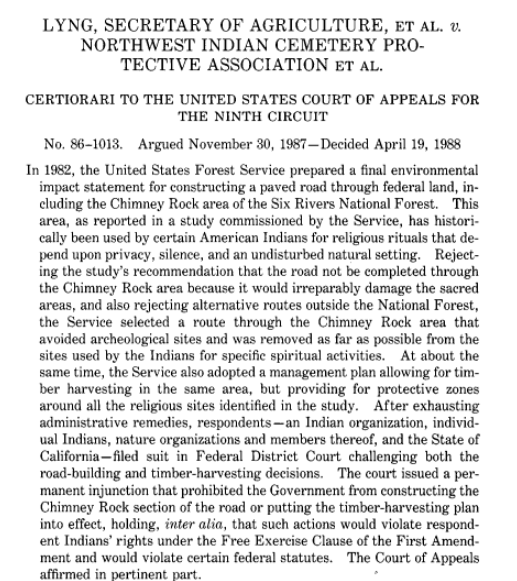

Case 4: Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1985)

The United States Forest Service (USFS) had plans to harvest timber as well as to build a paved road that would pass through federal land that included the Chimney Rock area of the Six Rivers National Forest, an area in California that had been used historically for religious rituals by Indigenous tribes. The Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Agency and the State of California sued the USFS in federal district court, claiming that the work would cause irreparable damage to sacred sites and rituals that required silence, privacy, and an undisturbed natural setting. The court agreed, issuing a permanent injunction that prohibited the timber harvesting or the building of the road in the area because it violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

The USFS appealed the decision, which was upheld by the Court of Appeals. The agency appealed again, bringing the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 5-3 decision, the Court sided with the USFS, ruling that “construction of the proposed road does not violate the First Amendment regardless of its effect on the religious practices of the respondents because it compels no behavior contrary to their belief.”[12]Khushbu Solanki, Buried, Cremated, Defleshed by Buzzards? Religiously Motivated Excarnatory Funeral Practices Are Not Abuse of Corpse, 18 RUTGERS J. L. & RELIGION 350 (2017). This article can be found in … Continue reading The Court also established a new definition for “substantial burden”—it only exists when the government imposes a sanction or denies benefits to those who would be entitled to them.

However, in the aftermath of this decision, Congress decided to designate the area a “wilderness” under the Wilderness Act,[13]To establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people, and for other purposes., Public Law 88-577, 88 Congress. 78 Stat. 890 (1964). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large … Continue reading and as such the harvesting could not take place and the road could not be built.

Case 5: Arizona v. Navajo Nation (2023)

In the mid-1800s, the U.S. government forced between 8,000 and 10,000 Navajo peoples to relocate from their lands in Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in what became known as “The Long Walk.” Unfortunately, the tribe found that the land that had been provided to them was nearly inhospitable—lack of rain and poor soil quality meant that their agricultural options were highly limited, and one out of four Navajo at the reservation died. The Treaty of Bosque Redondo[14]Navajoes: Treaty between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians, 15 Stat. 667 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law and U.S. Treaties and Agreements … Continue reading between the U.S. government and the Navajo people was signed on June 1, 1868. The Navajo agreed to remain on the reservation in Arizona and New Mexico and renounce claim to lands outside the reservation, as well as send their children for federal education. In exchange, the U.S. government would provide seeds, equipment, livestock, and other assistance for agriculture.

In Winters v. United States[15]Winters v. the United States, 207 U.S. 564, 578 (1908). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1908, the Supreme Court ruled that treaties that established reservations, such as the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, must ensure that tribes receive enough water to be able to sustain their people. Two decades ago, with severe drought hitting the southwestern United States, the Navajo sued, arguing that because the reservation had been established to be a “permanent home” for their people, the federal government was obligated to ensure that they received enough water to address their needs. However, Arizona, Colorado, and Nevada argued against the tribe in an effort to protect their own interests on the Colorado River, which is the main source of water in the region. The United States District Court for the District of Arizona sided with the states, but when the tribe appealed, the appellate court reversed the district court’s decision.

When the case eventually proceeded to the Supreme Court last year, the federal government argued alongside the states that the treaty did not require more than the recognition of the tribe’s water rights, while the Navajo argued that the treaty established the government’s responsibility to the tribe as “duty of protection.” In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the Court decided that based on the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, the U.S. government was not responsible for securing water for the Navajo people. You can learn more about this case in our dedicated blog post.

Learn More about Indigenous Life, Law, & Culture

HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law was created from a desire to consolidate the wealth of material available on indigenous American life and law, and to share the tremendous influence that indigenous peoples and their cultures have had on the development of the United States of America. With more than 4,000 titles and 2.3 million pages, this library includes an expansive archive of historic materials. Included in the database are hundreds of treaties, treaty-related publications, tribal codes, constitutions, federal case law, government reports, scholarly works, and the entirety of Title 25 (Indians) of the U.S. Code and Code of Federal Regulations.

Enjoy a 20% discount on the first-year subscription price of this invaluable resource throughout National Native American Heritage Month.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | Landmark Indian Law Cases (2002). Landmark Indian Law Cases. Buffalo, N.Y., William S. Hein & Co., Inc. This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Louis; Guttmann, Allen, Editors Filler. Removal of the Cherokee Nation: Manifest Destiny or National Dishonor (1962). This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑3 | Rory Flay, A Silent Epidemic: Revisiting the 2013 Reauthorization of the Violence against Women Act to Better Protect American Indian and Alaska Native Women, 5 AM. INDIAN L.J. 230 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑4 | 30 (5 Peters) U.S. 1 (1831) Cherokee Nation vs. the State of Georgia, The. This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library |

| ↑5 | Oliver H. Prince, Compiler. Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia Containing All Statutes and the Substance of All Resolutions of a General and Public Nature (2). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑6 | Chantelle van Wiltenburg, “The Center Cannot Hold”: Nation and Narration in American Indian Law, 47 AM. INDIAN L. REV. 127 (2023). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | W. R. L. Smith. Story of the Cherokees (1928). This title is located in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑8 | Margaret Campbell Haynes; June L. Melvin. Tribal and State Court Reciprocity in the Establishment and Enforcement of Child Support (1991). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics database. |

| ↑9 | Uriah, et al., Editors Barnes. Barnes’ Federal Code, Containing All Federal Statutes of General and Public Nature Now in Force (1919). This title can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Code database. |

| ↑10 | Sioux Indians: Treaty between the United States of America and different tribes of Sioux Indians, 15 Stat. 635 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law and U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library databases. |

| ↑11 | To revise, codify, and enact into positive law, Title 18 of the United States Code, entitled ‘Crimes and Criminal Procedure’., Public Law 80-772 / Chapter 645, 80 Congress. 62 Stat. 683 (1949) (1948). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑12 | Khushbu Solanki, Buried, Cremated, Defleshed by Buzzards? Religiously Motivated Excarnatory Funeral Practices Are Not Abuse of Corpse, 18 RUTGERS J. L. & RELIGION 350 (2017). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13 | To establish a National Wilderness Preservation System for the permanent good of the whole people, and for other purposes., Public Law 88-577, 88 Congress. 78 Stat. 890 (1964). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑14 | Navajoes: Treaty between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians, 15 Stat. 667 (1868). This treaty can be found in HeinOnline’s Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: History, Culture & Law and U.S. Treaties and Agreements Library databases. |

| ↑15 | Winters v. the United States, 207 U.S. 564, 578 (1908). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |