On May 5, 1925, Tennessee high school teacher John Scopes was charged with the crime of teaching his students about the science of human evolution. The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes would be argued two months later, with two of the most famous attorneys in the United States on opposing sides. The Scopes Monkey Trial, as it came to be known, was a national spectacle, and the first trial to be broadcast via the new medium of radio.

Keep reading to learn more about the events of the trial over ten days in July 1925, and about how the trial continues to cast a shadow over First Amendment jurisprudence through the present, using HeinOnline’s World Trials Library, U.S. Supreme Court Library, and Fastcase.

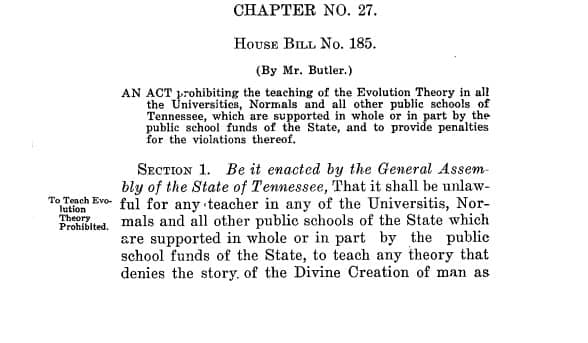

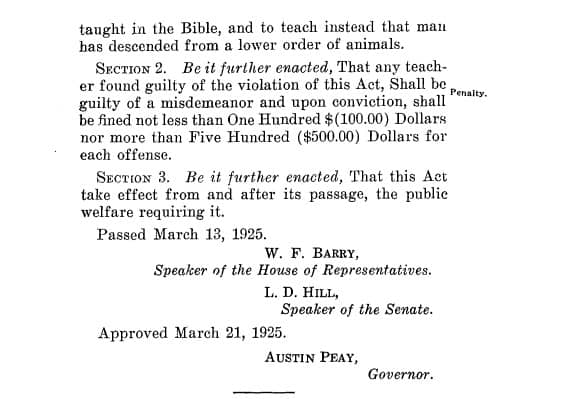

The Butler Act

The law that Scopes violated, popularly known as the Butler Act[1]1925 Tenn. Public Acts, 64th Gen. Assem., ch. 27, H.B. no. 185. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Sessions Laws Library. after its sponsor in the Tennessee legislature, made it illegal to “teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Governor Austin Peay signed the bill into law in March 1925. Almost immediately, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would fund the legal defense of anyone found guilty of teaching the science of human evolution in Tennessee.

On May 5, fewer than two months after the bill’s passage into law, the ACLU found its test case in the small town of Dayton. John Scopes, a high school science teacher, came forward and admitted to teaching human evolution, and was promptly charged under the Butler Act. Ironically enough, the textbook he taught from—Civic Biology—was mandated as part of the Tennessee state curriculum for public schools, making it impossible for high school teachers in the state to not violate the Butler Act.

The prosecution was led by District Attorney Tom Stewart, with the assistance of local attorney Gordon McKenzie. The World Christian Fundamentals Association, a nationwide organization of conservative Christian ministers, recruited William Jennings Bryan to serve as a further counsel for the prosecution. Bryan, one of the most famous men in the Untied States at the time, had run for president three times and served as Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson. Although Bryan was an evangelical Christian, his politics were in many ways progressive. He framed his opposition to evolution on the grounds that the theory played into the hands of Social Darwinists[2]Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and the rule of “the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.” Although this was a fundamental misreading of Darwin’s accounts of evolution, it did reflect widespread views at the time.

Bryan’s opponents in the defense were likewise progressive in their politics. The defense was led by Arthur Garfield Hays, co-founder of the ACLU, joined by the progressive lawyer Dudley Field Malone. They recruited Clarence Darrow, perhaps the most famous attorney in the country at the time. Darrow was a progressive attorney, and had earned renown as a defender of militant organized labor. He had also gained notoriety as the defense attorney for the famous murderers, Leopold and Loeb.[3]Maureen McKernan. Amazing Crime and Trial of Leopold and Loeb (1924). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. He and Bryan shared many political views in common but, unlike the devoutly Christian Bryan, Darrow was an avowed agnostic. The national media seized upon this detail, casting the trial as a clash between competing worldviews. The stage was set for a media circus in Tennessee.

The Trial

The trial unfolded over ten stiflingly hot days in July. Reporters from across the country flocked to the small town of Dayton. As trains packed with press rolled into the town, the brakemen yelled “All out for Monkeyville!”[4]Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. as passengers disembarked.

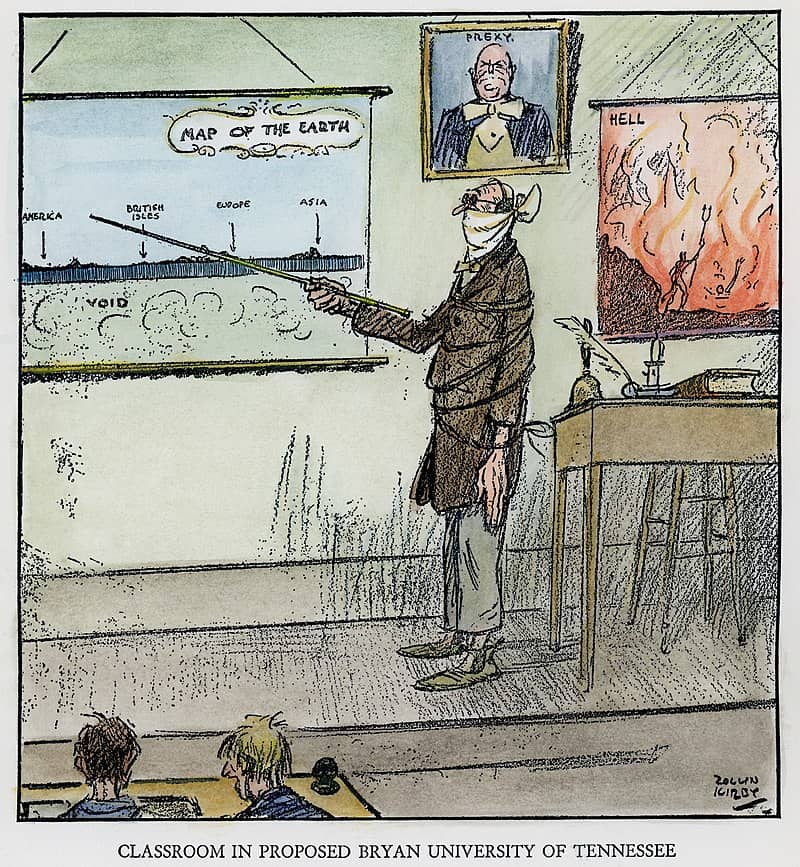

Even before it began, the outcome of the trial seemed like a foregone conclusion. In the State of Tennessee at the time, there was no effective separation between church and state. Daily Christian Bible study was mandated in public school. Each day of the trial began with a prayer,[5]World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). … Continue reading with the judge overseeing the proceedings—John Raulston—frequently citing scripture himself. The argument that the Butler Act violated the Establishment Clause of the United States Constitution, which prohibited the establishment of an official state religion, clearly did not bother the state government or judiciary. When Dudley Field Malone questioned Tom Stewart about the propriety of granting preferential treatment to one religion (i.e., Protestant Christianity) over all others, Stewart shrugged the question off and replied: “We are not living in a heathen country.”[6]World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). … Continue reading In the face of such blatant disregard for the constitutionality of the Butler Act, arguments in the case hinged upon the personalities and oratory of the two celebrity attorneys in the case.

Bryan appealed to the pride of the local audience, seeking to cast the ACLU-funded defense as outside agitators, intellectual elites who looked down upon the pious people of the South. There was some degree of truth to this. Classism and snobbery colored much of the national coverage of the trial. The journalist H.L. Mencken derisively referred to the region as the “Coca-Cola belt,” depicting it as a backwater of religious zealotry: “an Episcopalian down here in the Coca-Cola belt is regarded as an atheist. It sounds like one of the lies that journalists tell, but is an understatement of the facts.”[7]Ephraim London, Editor. World of Law: A Treasury of Great Writing about and in the Law, Short Stories, Plays, Essays, Accounts, Letters, Opinions, Pleas, Transcripts of Testimony; from Biblical Times to the Present (1960). This book can be … Continue reading Mencken depicted the people of Dayton as ignorant and superstitious, beholden to the whims of wild-eyed prophets and backwoods “sorcerers.” As far as satire goes, it’s rather lurid and mean-spirited.

Mencken’s accounts of life in the South played for big laughs in the Northern press, which delighted in the carnival atmosphere of the trial—during which a trained chimpanzee entertained spectators outside the courthouse—but it also played into the hands of Bryan and the prosecution. As Bryan (himself an outsider) posed, rhetorically: “If the people of Tennessee were to go into a state like New York…and tried to convince the people that a law they had passed ought not to be enforced, just because the people who went there didn’t think it ought to have been passed, don’t you think it would be resented as an impertinence?”[8]World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). … Continue reading

Bryan likewise appealed to his audience’s emotions by begging the age-old question of pathos-driven political discourse: will someone (please!) think of the children? The centerpiece of Bryan’s argument, on the fifth day of the trial, was an extended misreading of Darwin’s theories of evolution, in which he lamented that American schoolchildren were being taught that they descended from monkeys, quipping: “Not even from American monkeys, but from old world monkeys.”[9]World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). This … Continue reading In response to Bryan’s lamentation of children being taught evolution, Darrow delivered an impassioned speech in what could be considered to be the climax of the trial (although secondary sources indicate that there were many such moments over the course of the eventful trial): “For God’s sake let the children have their minds kept open—close no doors to their knowledge; shut no door from them. Make the distinction between theology and science. Let them have both.”[10]World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). This … Continue reading As a counterpoint to Bryan’s mischaracterization of evolution, the defense sought to call experts in biology as witnesses. Despite a final impassioned appeal by Malone—which Bryan himself admitted was “the greatest speech I have ever heard”[11]Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.—Raulston refused to allow expert testimony from any scientists or scholars in the case.

The trial adjourned for the weekend. With the defense unable to call any outside experts as witnesses, it looked to be heading for an uneventful and predetermined conclusion on Monday morning. “All that remains of the case…is the bumping off of the defendant,” H.L. Mencken wrote,[12]Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. shortly before skipping town. In leaving when he did, Mencken missed the most famous episode of the trial, which transpired on Monday afternoon. Just as the trial looked to be winding down, Darrow made a motion to call his opponent, Bryan, to the stand as a witness for the defense.

Darrow spent the remainder of the day cross-examining Bryan. The heat inside the courtroom was so stifling that the proceedings were moved outside to the front lawn of the Dayton courthouse. On a platform erected so that ministers could preach sermons while the trial unfolded indoors, Darrow spent two hours interrogating Bryan, exposing his ignorance of not only science, but the Bible as well. The crowd adored the spectacle, as the New York Times reported at the time:[13]Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. the audience “forgot for the moment that Bryan’s faith was its own…There was no pity for his admissions of ignorance of things boys and girls learn in high school.” After two hours, Raulston called an end to the proceedings. When the trial resumed the next day, he ordered the entire episode struck from the record, and hastily convened the jury to deliver a sentence. As expected, after five minutes of deliberation, the jury found Scopes guilty of violating the Butler Act, and Raulston ordered him to pay a fine of $100.

The Aftermath

William Jennings Bryan died in his hotel room five days after the conclusion of the trial. Scopes appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which ultimately overturned it on a technicality, but maintained that the Butler Act was constitutional. The Butler Act remained law in Tennessee until its repeal by the legislature in 1967. One year later, in Epperson v. Arkansas,[14]Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (United States Supreme Court 1968). This case can be found in Fastcase. the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all bans on the teaching of evolution in public schools violated the Establishment of Clause of the First Amendment. The separation between church and state was further strengthened in 1987, with Edwards v. Aguillard,[15]Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (United States Supreme Court 1987) This case can be found in Fastcase. when the Supreme Court ruled that teaching creationism alongside evolutionary science likewise violated the Establishment Clause. The case was further affirmed in 2005 by the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District,[16]Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 400 F.Supp.2d 707 (United States District Court, M.D. Pennsylvania 2005). This case can be found in Fastcase. when it ruled that teaching intelligent design was also a violation of the Establishment Clause.

Despite the numerous affirmations of the separation between church and state in the decades since the Scopes trial, there are signs that this trend may be reversing. Recent years have seen a series of rulings in the Supreme Court that lean into an interpretation of the First Amendment that privileges the Free Exercise Clause—which protects the right of an individual to practice or not practice a religion as they choose—over the Establishment Clause. In Carson v. Makin,[17]Carson v. Makin, 142 S.Ct. 1987 (United States Supreme Court 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase. in 2022, the Court ruled 6-3 that any public funding made available for secular public schools must be made available for religious schools as well, breaking with longstanding precedent that prohibited state funding for religious institutions. In another case in 2022, Kennedy v. Bremerton School District,[18]21-418 U.S. Reports 1 (2022) Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. This slip opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in another 6-3 ruling, the majority held that public school officials may conduct prayer services at official school events involving students. In her dissent to the ruling, Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the Court’s treatment of the Establishment Clause, arguing that the Court is “[charting] a different path, yet again paying almost exclusive attention to the Free Exercise Clause’s protection for individual religious exercise while giving short shrift to the Establishment Clause’s prohibition on state establishment of religion.”

Interestingly enough, some legal scholars have likewise observed a trend in which the Establishment Clause itself is taken up to argue in favor of incorporating overtly religious instruction into public schools. As Stern and DiFonzo write in “Dogging Darwin: America’s Revolt Against the Teaching of Evolution,“[19]Ruth C. Stern & J. Herbie DiFonzo, Dogging Darwin: America’s Revolt against the Teaching of Evolution, 36 N. ILL. U. L. REV. 33 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. “anti-evolutionists” not only invoke the Free Exercise Clause “to argue that religious freedom trumps the church-state divide. They also [claim], pursuant to the Establishment Clause, that maintaining a secular state imposes a decree of non-belief on Christian citizenry.” It remains to be seen how these questions will ultimately play out in the courts. However, the current Supreme Court looks increasingly willing to overturn longstanding precedent, as it did last year with its interpretation of the Due Process Clause in Dobbs v. Jackson[20]19-1392 U.S. Reports 1 (2021) Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization et al. This slip opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. that resulted in the elimination of federal abortion rights. In this light, a future replay of the Scopes Trial looks like a real possibility.

Keep Up With the Court

The 2023-2024 U.S. Supreme Court term begins next week with opening oral arguments. The last two terms have seen a number of landmark decisions, and this year looks to be no different, with at least two cases that raise questions pertaining to the First Amendment. To keep up with most important cases on the docket, make sure you’re subscribed to HeinOnline’s Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases. Preview provides comprehensive expert analysis of all cases argued before the Supreme Court prior to the arguments. The first issue of the term is live now on HeinOnline.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | 1925 Tenn. Public Acts, 64th Gen. Assem., ch. 27, H.B. no. 185. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Sessions Laws Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4, ↑12, ↑13 | Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑3 | Maureen McKernan. Amazing Crime and Trial of Leopold and Loeb (1924). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑5, ↑6, ↑8 | World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑7 | Ephraim London, Editor. World of Law: A Treasury of Great Writing about and in the Law, Short Stories, Plays, Essays, Accounts, Letters, Opinions, Pleas, Transcripts of Testimony; from Biblical Times to the Present (1960). This book can be found in HeinOnline’s Legal Classics collection. |

| ↑9, ↑10 | World’s Most Famous Court Trial, Tennessee Evolution Case; a Complete Stenographic Report of the Famous Court Test of the Tennessee Anti-evolution Act, at Dayton, July 10 to 21, 1925, including Speeches and Arguments of Attorneys (1925). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s World Trials Library. |

| ↑11 | Kevin O’Kelly, All out for Monkeyville: The Social Forces behind the Scopes Trial, 17 EXPERIENCE 13 (2007). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑14 | Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (United States Supreme Court 1968). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑15 | Edwards v. Aguillard, 482 U.S. 578 (United States Supreme Court 1987) This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑16 | Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, 400 F.Supp.2d 707 (United States District Court, M.D. Pennsylvania 2005). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑17 | Carson v. Makin, 142 S.Ct. 1987 (United States Supreme Court 2022). This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑18 | 21-418 U.S. Reports 1 (2022) Kennedy v. Bremerton School District. This slip opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑19 | Ruth C. Stern & J. Herbie DiFonzo, Dogging Darwin: America’s Revolt against the Teaching of Evolution, 36 N. ILL. U. L. REV. 33 (2016). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑20 | 19-1392 U.S. Reports 1 (2021) Dobbs, State Health Officer of the Mississippi Department of Health, et al. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization et al. This slip opinion can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |