On January 1, 2024, Mickey Mouse entered the public domain—partially. Mickey Mouse made his debut in the 1928 cartoon Steamboat Willie, one of the first cartoons produced with synchronized sound. After many extensions, Steamboat Willie is now in the public domain, and so too is the Steamboat Willie version of Mickey Mouse. Not wasting any time, at least two horror movies based on Steamboat Willie are currently in the works and more reinterpretations of this iconic mouse are sure to follow.

Mickey’s journey to this portion of the public domain is a winding road that fundamentally re-wrote United States copyright law. Using HeinOnline, let’s explore some of the laws that tried to keep Mickey in the Magic Kingdom and what’s in store next for this American icon.

Copyright Act of 1909

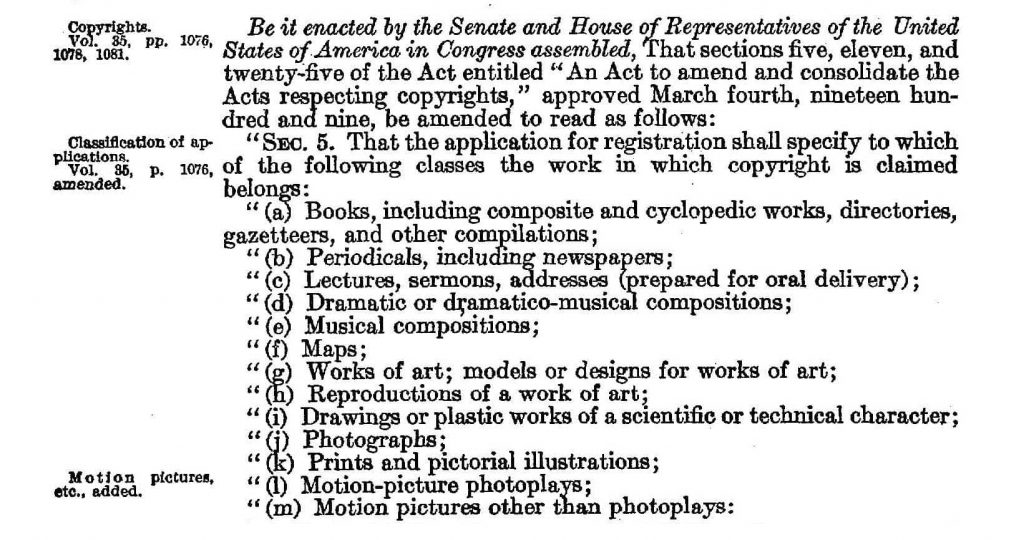

When Walt Disney released Steamboat Willie in 1928, the Copyright Act of 1909[1]35 Stat. 1075 (1909). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. was the law of the intellectual property land. When it became law, the 1909 Act was only the third revision to copyright law since the Copyright Act of 1790.[2]1 Stat. 124 (1790). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. The 1909 Act granted federal copyright protection to original works that were published with a copyright notice. Works published without a copyright notice were considered part of the public domain. The copyright term for any work was to last for 28 years. After 28 years, the author could renew his or her copyright for an additional term of 28 years, capping copyright duration for works at 56 years. An amendment in 1912[3]37 Stat. 488. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. added motion pictures and newsreels to the list of works covered under the 1909 Act.

Interestingly, some scholars have argued that Mickey Mouse has been in the public domain since 1928,[4]Douglas A. Hendenkamp, Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909, 2 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 254 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. asserting the copyright notice on Steamboat Willie was not properly formatted. Although Walt Disney produced, directed, wrote, and provided all the voices in Steamboat Willie, his name does not appear as the copyright holder on the movie’s title card—at least not on any available prints of the movie.[5]Douglas A. Hendenkamp, Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909, 2 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 254 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. The title card merely states “COPYRIGHT MCMXXIV” without listing a copyright holder, which, under this argument, would not comply with the 1909 Act.[6]Douglas A. Hendenkamp, Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909, 2 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 254 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. While an interesting legal argument, it is ultimately moot after January 1.

Copyright Act of 1976

The next major revision to U.S. copyright law came in 1976, 48 years after the release of Steamboat Willie and the world’s introduction to Mickey Mouse. Steamboat Willie was approaching the expiration of its copyright when the Copyright Act of 1976[7]90 Stat. 2541 (1976). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. became law. The 1976 Act completely overhauled how copyright duration was determined.

It eliminated the 28-year term and renewal and instead changed the copyright term to last for the life of the author plus an additional 50 years after his or her death (Walt Disney died in 1966). This new rule only applied to works created on or after January 1, 1978. Works published before 1922 entered the public domain.[8]Kaitlyn Hennessey, Intellectual Property – Mickey Mouse’s Intellectual Property Adventure: What Disney’s War on Copyrights Has to Do with Trademarks and Patents, 42 W. NEW ENG. L. REV. 25 (2020). This article is found in … Continue reading Luckily for Mickey, his birth year was 1928. Post-1922 works, if their copyrights had already been renewed, were extended to a full 75 years.[9]Victoria A. Grzelak, Mickey Mouse &(and) Sonny Bono Go to Court: The Copyright Term Extension Act and Its Effect on Current and Future Rights, 2 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 95 (2002). This article is found in … Continue reading

The Walt Disney Company allegedly lobbied Congress to pass the 1976 Act.[10]Kaitlyn Hennessey, Intellectual Property – Mickey Mouse’s Intellectual Property Adventure: What Disney’s War on Copyrights Has to Do with Trademarks and Patents, 42 W. NEW ENG. L. REV. 25 (2020). This article is found in … Continue reading With its passage, Mickey Mouse’s copyright, which had been set to expire in 1984, was extended until 2003.

Mickey Mouse and Sonny Bono: The Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998

Perhaps the most well-known revision to copyright law is the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998[11]112 Stat. 2827. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large.—also pejoratively known as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act. The Act was named in honor of Congressman Sonny Bono, who had been one of the bill’s sponsors but died before its passage. Before arriving on Capitol Hill, Bono had been a successful musician, most famously as part of the duo Sonny and Cher. Bono’s music industry past no doubt factored into his support of the bill.

The Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) was a drastic change to copyright law.[12]Christina N. Gifford, The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 30 U. MEM. L. REV. 363 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Major copyright term extensions under the act were:

- for works created after January 1, 1978, copyright lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years, instead of 50 years

- anonymous works or works made for hire are copyrighted for 95 years from first publication and 120 years from creation, whichever term is shorter

- this was an extension from the 1976 Act, which fixed the terms at 75 years after first publication or for 100 years after creation, whichever was shorter

- for works created before January 1, 1978, whose copyright had been renewed, their copyright term lasts for 95 years from publication

The CTEA effectively froze any new works from entering the public domain until 2018.[13]Christina N. Gifford, The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 30 U. MEM. L. REV. 363 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Disney supported its passage, with then-CEO Michael Eisner personally going to Capitol Hill to lobby for its passage[14]Christina N. Gifford, The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 30 U. MEM. L. REV. 363 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. and having at least one face-to-face meeting with Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott.[15]Holly Lechner, Mickey Mouse – Finally Whistling His Way into the Public Domain, 14 CYBARIS INTELL. PROP. L. REV. 71 (2023). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. While the Disney company generally keeps its lobbying activities close to the vest, it is estimated the House of Mouse spent some $6.3 million[16]Holly Lechner, Mickey Mouse – Finally Whistling His Way into the Public Domain, 14 CYBARIS INTELL. PROP. L. REV. 71 (2023). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. on lobbying efforts for the CTEA, giving money to 18 of the bill’s 25 sponsors.[17]Holly Lechner, Mickey Mouse – Finally Whistling His Way into the Public Domain, 14 CYBARIS INTELL. PROP. L. REV. 71 (2023). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library.

Disney’s support for the act, as well as its timely passage to once again extend the copyright on Mickey Mouse and the brand’s other founding characters, gave the act its derisive “Mickey Mouse Protection Act” nickname. But Disney wasn’t the act’s only prominent champion, and it certainly wasn’t its only beneficiary. The estates of George Gershwin,[18]Richard A. Posner, Constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act: Economics, Politics, Law and Judicial Technique in Eldred v. Ashcroft, 2003 SUP. CT. REV. 143 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. Irving Berlin, and Richard Rogers and Oscar Hammerstein II[19]Jessica Edmundson , Elizabeth Townsend Gard , Jane Ginsburg , Jule Sigall , Siva Vaidhyanathan , Kenneth D. Crews, Nina Paley & David Carson, Conversations with Renowned Professors and Practitioners on the Future of Copyright, 14 TUL. J. … Continue reading also lobbied extensively for the CTEA’s passage. The CTEA ultimately affected some 400,000 works,[20]Jonathan Schwartz, Will Mickey Be Property of Disney Forever? Divergent Attitudes toward Patent and Copyright Extensions in Light of Eldred v. Ashcroft, 2004 U. ILL. J.L. TECH. & POL’y 105 (2004). This article is found in … Continue reading including The Great Gatsby, Winnie the Pooh, Showboat, and the works of Virginia Woolf.

Sonny Bono and the Supreme Court

The CTEA was controversial from its passage; a search in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library brings up scholarly articles on the law with scathing titles such as:

- The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act: A Violation of Progress and Promotion of the Arts (2003).

- The Dubious Constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act (2002).

- The Copyright Term Extension Act: Is Life Plus Seventy Too Much? (1995).

- For Limited Times – Making Rich Kids Richer Via the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1996 (1996)

The CTEA’s constitutionality was challenged before the U.S. Supreme Court in Eldred v. Ashcroft.[21]537 U.S. 186 (2002). This case is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. Eric Eldred, an Internet publisher, along with several other publishers whose businesses relied on public domain works argued that Congress overstepped its power when it extended copyrights for already published works. The Supreme Court upheld the CTEA by a 7–2 vote.

What’s Next for Mickey Mouse?

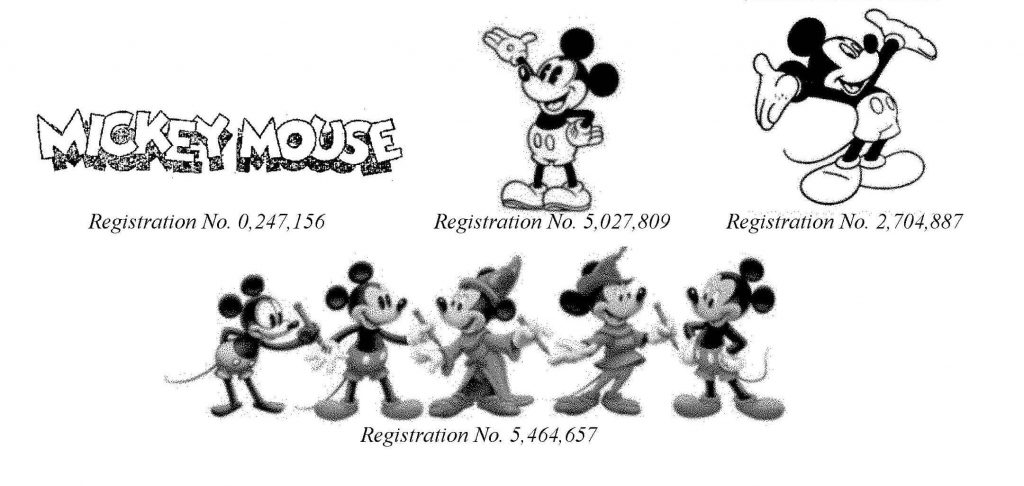

Although many academics predicted Disney would once again try to extend its copyright on Steamboat Willie, the film and its iteration of Mickey Mouse entered the public domain without any legislative protest. Mickey Mouse’s physical appearance has evolved over the last 96 years, and the image we most associate with him today—rounder, cuter, more mouse than steamboat rat, wearing white gloves, yellow shoes, and red shorts—is still protected by copyright. Disney’s trademarks on Mickey,[22]Sarah Sue Landau, Of Mouse and Men: Will Mickey Mouse Live Forever?, 9 NYU J. INTELL. PROP. & ENT. L. 249 (2020). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. which it has vigorously and successfully defended in court for years, will also continue to give it control over the character.

Mickey and Minnie Mouse have now dipped their toes into the public domain. The rest of the Disney Fab Five—Pluto, Goofy, and Donald Duck—are set to join them in 2025, 2027, and 2029, respectively.

Hot Dog—More Fun on the HeinOnline Blog

Here at the HeinOnline Blog, we’ve covered the murky intersection between pop culture and intellectual property law before. If you liked this post, be sure to check out these similar posts from the past:

- Coming for Katy Like a Dark Horse: Copyright Law in the U.S.

- Everything or Nothing: The Copyright History of James Bond

- Come on Barbie, Let’s Go Sue Somebody: Protecting the Barbie Trademark

- It’s a Colorful Life: Colorizing Black and White Movies

And of course, subscribe to the blog so you don’t miss a post!

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | 35 Stat. 1075 (1909). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 1 Stat. 124 (1790). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑3 | 37 Stat. 488. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑4, ↑5, ↑6 | Douglas A. Hendenkamp, Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909, 2 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 254 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | 90 Stat. 2541 (1976). This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑8, ↑10 | Kaitlyn Hennessey, Intellectual Property – Mickey Mouse’s Intellectual Property Adventure: What Disney’s War on Copyrights Has to Do with Trademarks and Patents, 42 W. NEW ENG. L. REV. 25 (2020). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑9 | Victoria A. Grzelak, Mickey Mouse &(and) Sonny Bono Go to Court: The Copyright Term Extension Act and Its Effect on Current and Future Rights, 2 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 95 (2002). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑11 | 112 Stat. 2827. This law is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large. |

| ↑12 | Christina N. Gifford, The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 30 U. MEM. L. REV. 363 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑13, ↑14 | Christina N. Gifford, The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, 30 U. MEM. L. REV. 363 (2000). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑15, ↑16, ↑17 | Holly Lechner, Mickey Mouse – Finally Whistling His Way into the Public Domain, 14 CYBARIS INTELL. PROP. L. REV. 71 (2023). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑18 | Richard A. Posner, Constitutionality of the Copyright Term Extension Act: Economics, Politics, Law and Judicial Technique in Eldred v. Ashcroft, 2003 SUP. CT. REV. 143 (2003). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑19 | Jessica Edmundson , Elizabeth Townsend Gard , Jane Ginsburg , Jule Sigall , Siva Vaidhyanathan , Kenneth D. Crews, Nina Paley & David Carson, Conversations with Renowned Professors and Practitioners on the Future of Copyright, 14 TUL. J. TECH. & INTELL. PROP. 1 (2011). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑20 | Jonathan Schwartz, Will Mickey Be Property of Disney Forever? Divergent Attitudes toward Patent and Copyright Extensions in Light of Eldred v. Ashcroft, 2004 U. ILL. J.L. TECH. & POL’y 105 (2004). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑21 | 537 U.S. 186 (2002). This case is found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑22 | Sarah Sue Landau, Of Mouse and Men: Will Mickey Mouse Live Forever?, 9 NYU J. INTELL. PROP. & ENT. L. 249 (2020). This article is found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |