Vaccination efforts against COVID-19 are underway across the world. In the United States, two vaccines have been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for use, one developed by Moderna and one by Pfizer-BioNTech. Limitations on the amount of available doses have led the Centers for Disease Control to provide recommendations on who should be vaccinated first, but eventually the general public will be able to receive the vaccine. Its widespread availability will naturally lead to questions for both the public and for policy makers on whether vaccination against COVID-19 will be a requirement to board a plane, return to school, attend a concert, visit a theme park, have a beer at a bar, or participate in any other similar activity that has been upended by the pandemic.

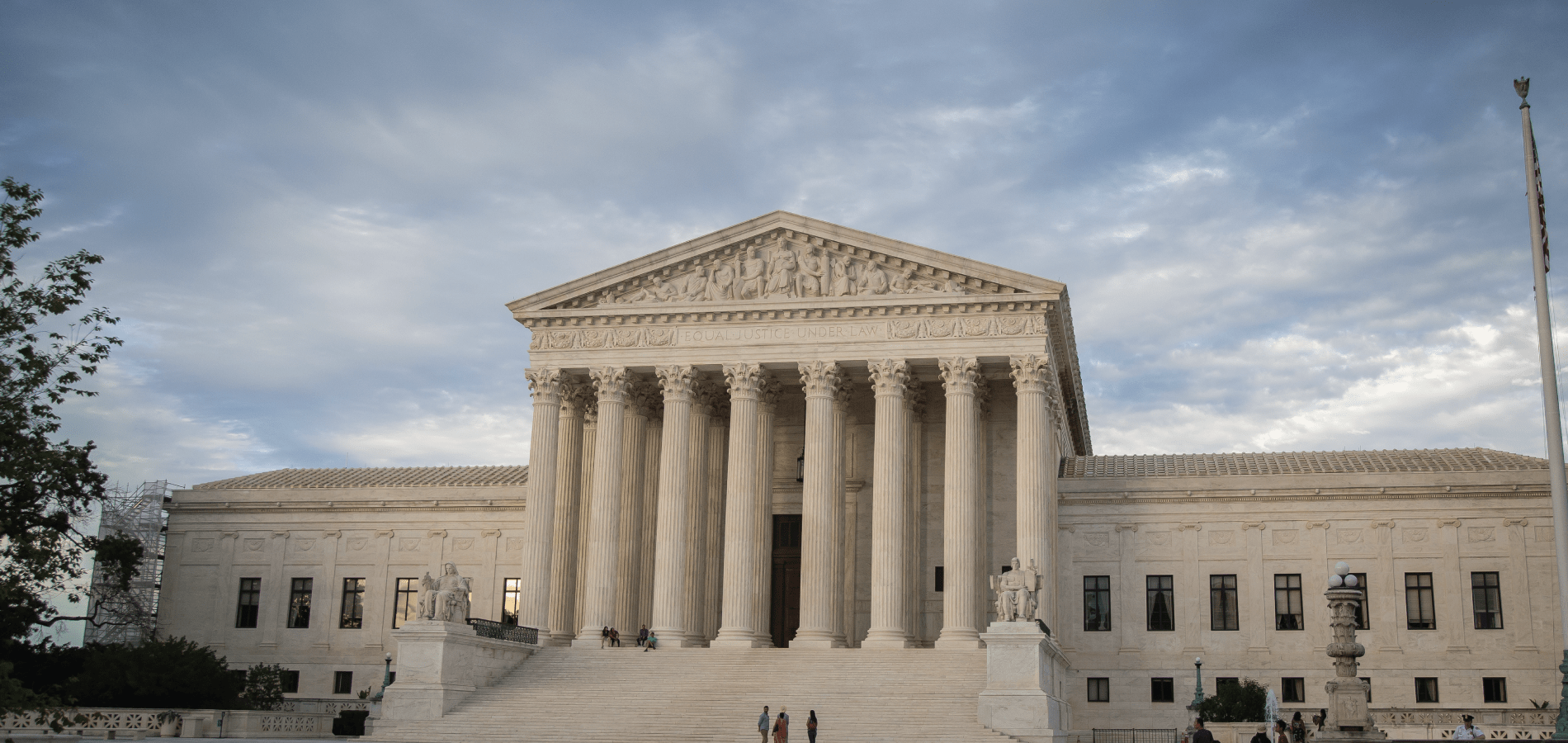

The ethics of compulsory vaccination have been debated since the advent of vaccines, a debate than in turn has required the courts to weigh in, providing precedent that may illuminate what could happen with the COVID-19 vaccine. Join us on a medico-legal journey through the following databases to explore the history of compulsory vaccination:

- Animal Studies: Law, Welfare and Rights

- Law Journal Library

- Legal Classics

- State Reports: A Historical Archive

- State Statutes: A Historical Archive

- U.S. Congressional Documents

- U.S. Statutes at Large

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

Sick to Death, Literally

Since humankind first slithered from the primordial ooze, we have been bedeviled by infectious disease, scourges manifested in myriad debilitating, contagious, and deadly permutations, and in turn have grasped for any means to mitigate their seemingly unstoppable spread. When bubonic plague decimated Europe in the 14th century, one remedy called for strapping a live chicken to the swollen buboes of a plague victim, hoping to draw the disease out of the human and into the animal. Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist, penned the encyclopedic Historia naturalis in AD 77, which contained hundreds of prescriptions of varying bizarre nature for everything from sneezes to seizures. The 4th century spinoff Medicina Plinii, which borrowed heavily from and expanded upon Pliny’s work, was hugely influential and still being used in the Middle Ages. Examples of cures prescribed in these pharmacopoeias include a tonic of boar’s urine with honey and vinegar for epilepsy and wearing a nail used in a crucifixion (seasoned with cow’s manure) to cure malaria.

Behind all this apparent ignorant insanity was the simple fact in the pre-antibiotic epoch, people were dying of all sorts of diseases rapidly and often. Our modern minds may scoff at the idea of bacteria leaping out of a man and into nearby poultry, but plague can be fatal within three days of symptom onset without treatment, and in the face of such grim odds one is willing to try anything.

In the 1700s, every tenth death in England was from smallpox. Smallpox is a highly contagious disease that has afflicted humankind since the days of the Egyptian pharaohs. Its initial, common symptom, a high fever, delineated itself from other afflictions by the onset of a body-wide rash that evolved into hardened pustules that eventually scabbed over and flaked off, leaving behind deep, permanent scarring, especially on the face. Nine out of ten people who contracted smallpox were children under 10 years old. The majority developed what is known as ordinary type smallpox; of those who got it, 30% died. Malignant and hemorrhagic smallpox were rarer but almost always fatal. In addition to permanent scarring, some survivors were greatly disfigured by the disease; many also became blind or deaf. George Washington and Elizabeth I both survived smallpox but bore its physical scars on their faces for the rest of their lives; royals Louis XV of France and William II of Orange, father to a future king of England, were killed by it. Inoculation against smallpox, or intentionally exposing a healthy individual to a small amount of the virus, either by inhaling smallpox scabs or by pricking the skin of a non-ill person and applying pus from an active smallpox patient into the wound, had been practiced in China since the 10th century. In 1717, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, observed smallpox inoculation while abroad and was so amazed by its efficacy that she promoted the practice upon her return to England. But while inoculation against smallpox, or variolation as it was also known, was effective, it was also dangerous. People who had been inoculated still actively spread smallpox and could still develop a severe or even fatal infection. In essence, the cure necessitated the perpetuation of the disease, an Asclepiusian snake eating its tail.

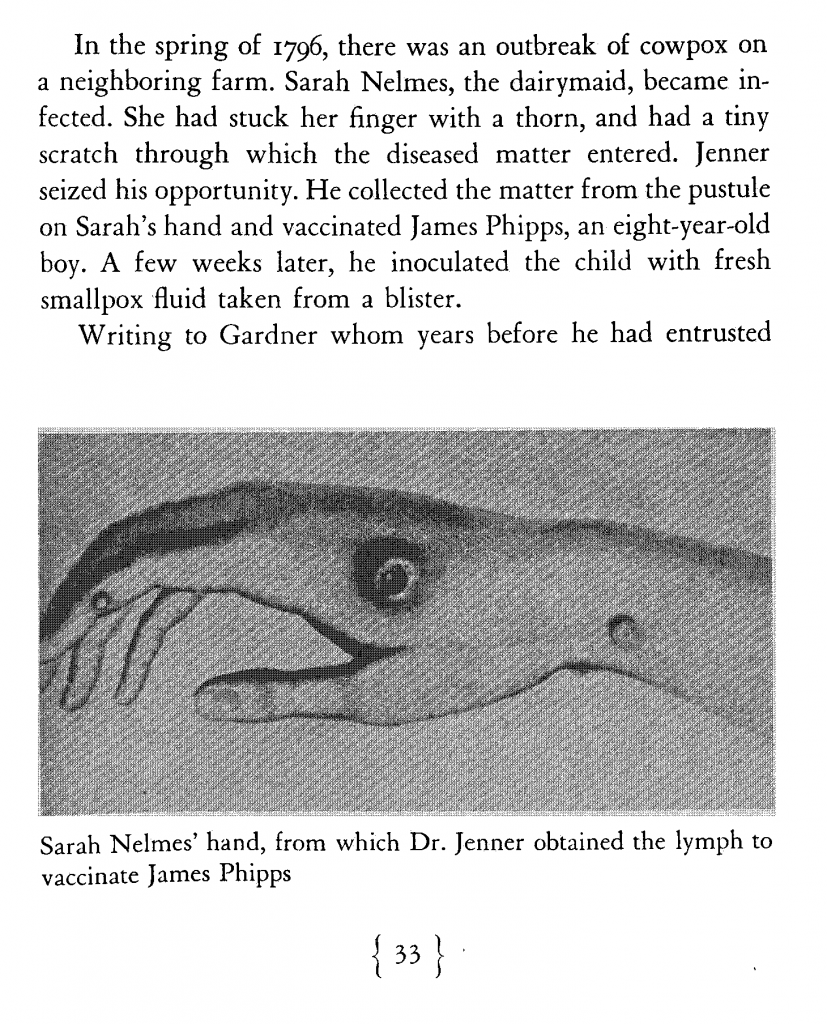

The World’s First

As a doctor in bucolic Gloucestershire, Edward Jenner was familiar with not just smallpox but also cowpox, a smallpox-like disease in cows that affected the animal’s udder, causing pus-filled blisters that left behind pitted scars. Through the course of their daily duties, milkmaids spread the disease from cow to cow and even into themselves through open wounds on their hands, and it was common knowledge among locals that a cowpox-afflicted milkmaid was somehow generally immune to smallpox. In 1796, Jenner tested this belief by scraping pus from the cowpox-infected hands of dairymaid Sarah Nelmes and pricking 8-year-old James Phipps with it. Several weeks later, he inoculated young James with live smallpox and the boy developed no infection. After two more years of testing, Jenner published his findings and methods, thus introducing the world to the first vaccine, so deriving its name from vacca, the Latin for cow, in variolae vaccinae, literally “smallpox of the cow.”

Vaccination was controversial from its birth. There were fears that vaccinated children would acquire characteristics of their bovine biological protectors—complete with horns and mooing. Jenner’s efforts to train doctors in his vaccine’s proper administration spread the method across the globe, but despite its effectiveness, fears and doubts still fomented, exacerbated by bad reactions and improperly administered vaccines. Smallpox vaccination of infants was mandated in England and Wales for the first time by the Vaccination Act 1853, with failure to comply punishable by fine or imprisonment. The Vaccination Act 1867 expanded mandated vaccination to all children up to the age of 14, with stiffened penalties for noncompliance enacted in the Vaccination Act 1871. Despite these punitive measures, a study by Her Majesty’s government found that one third of children born in 1897 were not vaccinated. In response to these findings, the Vaccine Act 1898 still mandated vaccination, but for the first time permitted conditional exemption to parents, hoping that a balance between liberty and compulsion would steer more parents to vaccinate their children.

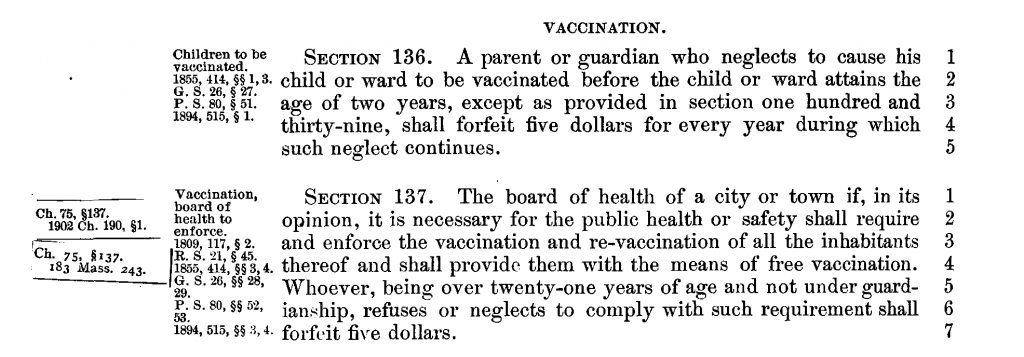

Over in the United States, compulsory smallpox vaccination was first adopted in Massachusetts in 1809, with proof of vaccination a condition of public school attendance being mandated in that state in 1855. But it was not without controversy. Montague Leverson, a lawyer and homeopathic doctor, was a member of the Anti-Vaccination Society of America, formed in 1879. He characterized vaccination as “a medical fad” whose imposition upon the public was “the most infamous of tyrannies.” Still, by the dawn of the 20th century, ten other states had joined Massachusetts in adopting compulsory vaccination laws and thirteen states had laws on the books that excluded unvaccinated children from public schools.

The Needs of the Many

In February of 1902, an outbreak of smallpox in Cambridge, Massachusetts prompted the Board of Health to use its powers under ch. 75 §137 to require residents to be vaccinated or re-vaccinated in the interest of public safety, with an exemption for children who had been certified as unfit for vaccination by a physician. Failure to comply would result in a fine of $5.

Local pastor Henning Jacobson refused to be re-vaccinated, claiming his smallpox vaccination as a child had caused a serious reaction, which Jacobson’s son also experienced upon his own eventual vaccination. Due to his refusal, Jacobson was fined and arraigned, but he refused to pay the fine, arguing that a “compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary and oppressive,” “not justified by necessity,” and a “violation of liberty.” Eventually, Jacobson’s appeals made their way to the US Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court rejected Jacobson’s arguments without passing judgment on whether Jacobson or his offspring had a legitimate claim to medical exemption from vaccination (an issue Jacobson never produced experts on to testify in court). Instead, the Court concerned itself with addressing whether Massachusetts acted within its authority when it allowed the Board of Health to compel vaccination for the residents of Cambridge, or whether in doing so it violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Ultimately, the Court held that “the liberty secured by the Constitution of the United States to every person within its jurisdiction does not import an absolute right in each person to be, at all times and in all circumstances, wholly freed from restraint,” and went on to say that:

If the mode adopted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the protection of its local communities against smallpox proved to be distressing, inconvenient or objectionable to some—if nothing more could be reasonably affirmed of the statute in question—the answer is that it was the duty of the constituted authorities primarily to keep in view the welfare, comfort and safety of the many, and not permit the interests of the many to be subordinated to the wishes or convenience of the few…. in every well-ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.

The Court was careful to note, however, that “the police power of a State… may be exerted in such circumstances or by regulations so arbitrary and oppressive in particular cases as to justify the interference of the courts to prevent wrong and oppression.” Had Jacobson produced evidence that he was unfit for vaccination, for example, and the law still compelled him to be vaccinated, to do so would be “cruel and inhuman to the last degree.” To avoid such outcomes, the Court cautioned that “[g]eneral terms should be so limited in their application as not to lead to injustice, oppression or absurd consequence. It will always, therefore, be presumed that the legislature intended exceptions to its language which would avoid results of that character.”

Henning Jacobson was ruled fit for vaccination and he eventually paid his fine. He died in 1930 at the age of 74.

A Disease Dies, and Controversy Persists

In response to the Court’s decision in Jacobson, the Anti-Vaccination League of America was formed, later making an appearance in a case before the Massachusetts Supreme Court that challenged smallpox vaccination as a condition of school attendance; the Massachusetts Supreme Court, citing Jacobson, upheld the statute.

Jacobson was reaffirmed by the US Supreme Court in the 1922 case Zucht v. King, when the Court ruled that a San Antonio school district was within its right to exclude unvaccinated children from its schools. Today, all 50 states have legislation requiring students to be vaccinated as a condition of attending public school with allowances for medical exemptions. Massachusetts is one of the 45 states (plus the District of Columbia) that also allows vaccination exemptions for religious reasons. Fifteen states also permit “philosophical exemptions,” that is, persons may opt out of vaccination for personal, moral, or other reasons.

Controversy around vaccination and the ethics of making it compulsory is as active today as it was during the time of Jacobson and Leverson. Concern about a link between vaccination and autism has led to an increasing number of Americans to opt out of vaccinating their children. In 1986, Congress passed the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act to insure a stable supply of vaccines by shielding manufacturers from financial liability for vaccine injury claims, to mandate reporting of adverse events following vaccination, and to create a claim procedure under a federal no-fault system to compensate vaccine-related incidents.

As for Jenner’s nemesis, that foe of the first vaccine, wild smallpox was eradicated in 1977 through rigorous vaccination campaigns, and routine vaccination against it for the American public was stopped in 1972. Concern, however, of smallpox being used as part of a biological warfare attack keeps millions of doses of the smallpox vaccine in the Strategic National Stockpile in case of such an event.

Shots Fired, Right into the Inbox

Get your daily dose of Hein blog posts straight into the subcutaneous tissue of your inbox by hitting that subscribe button below.