In the early days of quarantine, nearly a hundred years ago, all the way back at the end of March, one thing united us all. No, not the sewing struggle to make our own masks or collective worrying over when we would ever see a roll of Charmin in the wild again. It was Tiger King. The true crime-character study-have-to-see-it-to-believe-it docuseries had more than 34 million views in the U.S. within its first 10 days on Netflix, and was an inescapable recommendation, topic of discussion, and fodder for many quality memes.

In case you somehow missed out, a brief synopsis: Tiger King chronicles the years-long feud between Oklahoma private zoo owner Joe Exotic (real name: Joseph Maldonado-Passage, né Schreibvogel) and Florida animal sanctuary operator Carole Baskin as their acrimony escalates through public bickering, threatening videos, and lawsuits, and eventually culminates in a murder-for-hire plot orchestrated by Joe Exotic against Baskin. Interspersed throughout the eight episodes are polygamy, country music videos, and failed presidential and gubernatorial ambitions. The series ends with Joe Exotic in federal prison serving a 22-year sentence for attempting to have Carole Baskin killed.

When caught up in the show’s relentless twists and turns, it is easy to lose sight of what is perhaps the most shocking revelation in the show: America has a tiger problem. By some estimates, there are more tigers in captivity in America than there are left in the wild. These animals live in countless roadside zoos, in backyards, and, infamously, in a public-housing high-rise in Harlem. Because of patchwork county, state, and federal laws regarding big cat ownership, no one actually knows how many tigers live in America outside of AZA-accredited zoos; the most common estimate ranges from 5,000 to 7,000 tigers, but others estimate the numbers could be even higher—as many as 15,000. Let’s explore this issue and the laws that attempt to regulate it, while also gaining some behind-the-scenes understanding of Joe Exotic’s legal troubles using HeinOnline.

Hey all you cool cats and kittens, don’t miss out! Make sure you have the databases we’ll be referencing to follow along.

- Animal Studies: Law, Welfare and Rights

- Code of Federal Regulations

- Fastcase

- Federal Register

- Law Journal Library

- U.S. Congressional Documents

- U.S. Statutes at Large

- U.S. Treaties and Agreements

Can’t Hug Every Cat

A Feud Begins

Viewers of Tiger King know that one of the central issues that fueled the feud between Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin is cub petting. Cub petting is a primary source of income for operations like Joe Exotic’s. The principle behind it is simple: for the right price, you too can cuddle a baby tiger. As explained in the show, Joe Exotic took his animals on the road for years, visiting schools and malls and letting the public pay to pet the cubs. Doc Antle, whose Myrtle Beach Safari is also featured in Tiger King, will let you feed an African elephant and play with tiger cubs today for the modest fee of $339 per person.

The central objection to cub petting, as explained by Baskin in the show, is that because cub petting is so profitable, it encourages tiger breeding to ensure there is always a fresh supply of cute cubs on hand for selfies. Adult female tigers produce litters more frequently than they naturally would in the wild, and their cubs are often inbred, unhealthy, and mixed-breed (a detail that becomes important later). Cubs are commonly removed from their mothers when they are only hours old in order to become accustomed to human handling and primed for the camera. Once those cubs become too big and too dangerous to handle, and are no longer “cute enough,” they are sometimes kept and raised to maturity (and therefore able to be bred, producing more cubs to perpetuate the cycle), sold, or even killed. The Animal Welfare Act, which sets the minimum standards of care for commercial and research animals, only permits cub petting of animals between eight and twelve weeks of age, but the Act’s minimum standards do nothing to deter cub petting itself, provided it is not “rough or excessive,” a definition that is subjective at best and inviting of abuse at worst.

From the Jungle into Cages

Internationally, tigers are protected by Articles I and II of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, which entered into force on July 1, 1975. CITES aims to ensure that the international trade of any wild animals or plants does not threaten the species’ survival in the wild, with more than 35,000 species of animals and plants falling under its protection. Examples of the kinds of trade CITES regulates would be furs, shark fins, and ivory. The demand for tiger bone and other tiger parts is a major driver in wild tiger poaching, with tiger farms in China supplying parts into the illegal wildlife trade. With demand for tiger parts so lucrative, and so many tigers living in unregulated captivity in the United States, the concern is that these captive-bred tigers could be trafficked unless steps are taken to regulate the captive tiger population.

Federal Laws Try to Lend a Helping Paw

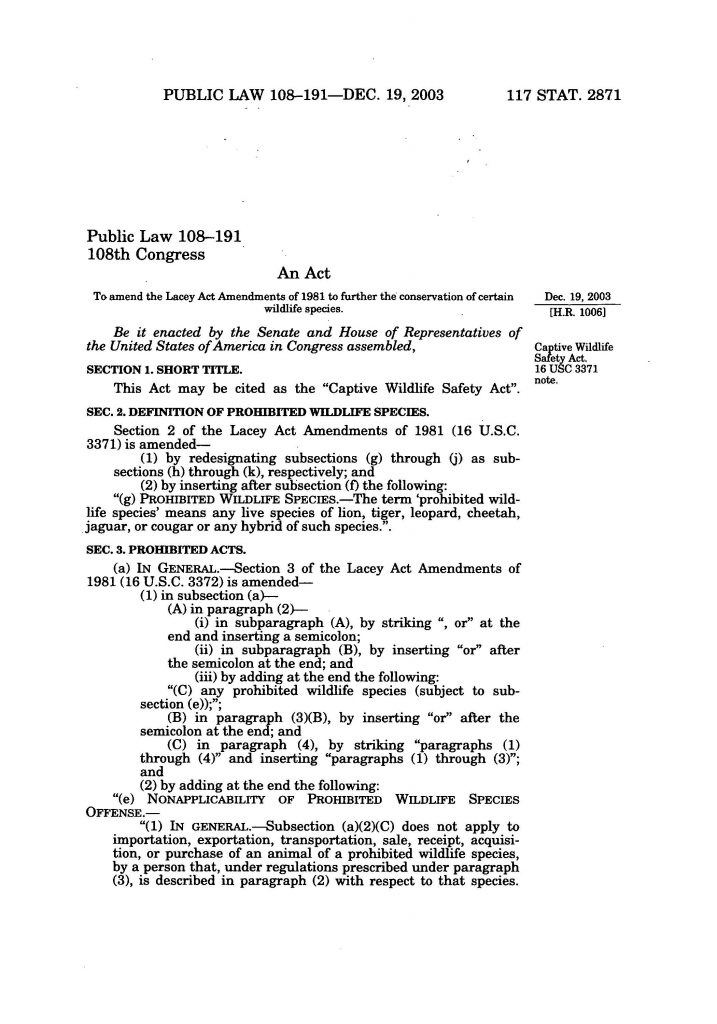

Congress is not unaware of the lack of federal regulations on big cat ownership. In 2007, the Captive Wildlife Safety Act (CWSA) took effect. This amendment to the Lacey Act makes it illegal to import, export, buy, sell, transport, or otherwise receive live big cats across state lines or the U.S. border. Designed as an attempt to curb the interstate selling of big cats as pets, the Act does not outlaw private big cat ownership. USDA license holders are exempt from the Act’s provisions.

While an important regulatory step, the CWSA is not the federal solution sought for addressing private big cat ownership. In a legislative hearing on the Act in 2003, Matt Hogan, then-Deputy Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service, offered this testimony:

Although we acknowledge that the increasingly popular practice of keeping “big cat” species as pets has created a growing concern about both the safety of the public and the welfare of these animals, the Department cannot at this time support this legislation … most of the thousands of big cats in the pet trade in this country are captive-bred animals. While big cat trafficking is a public safety problem and animal welfare concern, it is not, at its core, a wildlife conservation issue.

It may sound shocking that John Smith and Jane Doe can keep live tigers in their backyard and this is not considered a “wildlife conservation issue.” However, as mentioned earlier in this post, most of the tigers in private ownership in the United States are, affectionately, mutts. Because they are often crossbreeds of different tiger subspecies, ligers, or other hybrids, their compromised genetics make them unsuitable for conservation breeding and for eventual release into the wild. It was not until 2016 that these so-called “generic” tigers came under the protection of the CWSA—no buying or selling across state lines, unless you have a USDA license. It was this enforcement of the sale of generic tigers that would eventually compound Joe Exotic’s legal woes.

So, how hard is it to get a USDA license that allows interstate sale of tigers? It requires filling out this application, paying a very modest fee, and agreeing to USDA compliance inspections to make sure animals are being appropriately housed and cared for, meaning animals have food, water, and clean enclosures that are large enough to allow them to stand up and turn around. A federal exhibitor’s license would circumvent any state or local laws in place, even if they might be stricter than laws at the federal level. States like Ohio, which earned praise for its ban on ownership of “dangerous wild animals” after the Zanesville massacre, still exempts license holders and, bizarrely, dangerous wild animals that have been trained to assist the blind.

Where Do We Go From Here?

A Bill Tries (and Tries and Tries) to Become Law

The proposed law touted as the solution to private big cat ownership is the Big Cat Public Safety Act, discussed in Tiger King, which amends the CWSA to prohibit the private possession and breeding of big cats and explicitly outlaws cub petting. First introduced in 2012 in the 112th Congress, the Act has prowled through the 113th, 114th, and 115th Congresses with no success; it was again introduced this past February. Passage of the Act is strongly supported by the World Wildlife Fund, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, the Animal Welfare Institute, the Animal Legal Defense Fund, and, yes, Carole Baskin’s Big Cat Rescue.

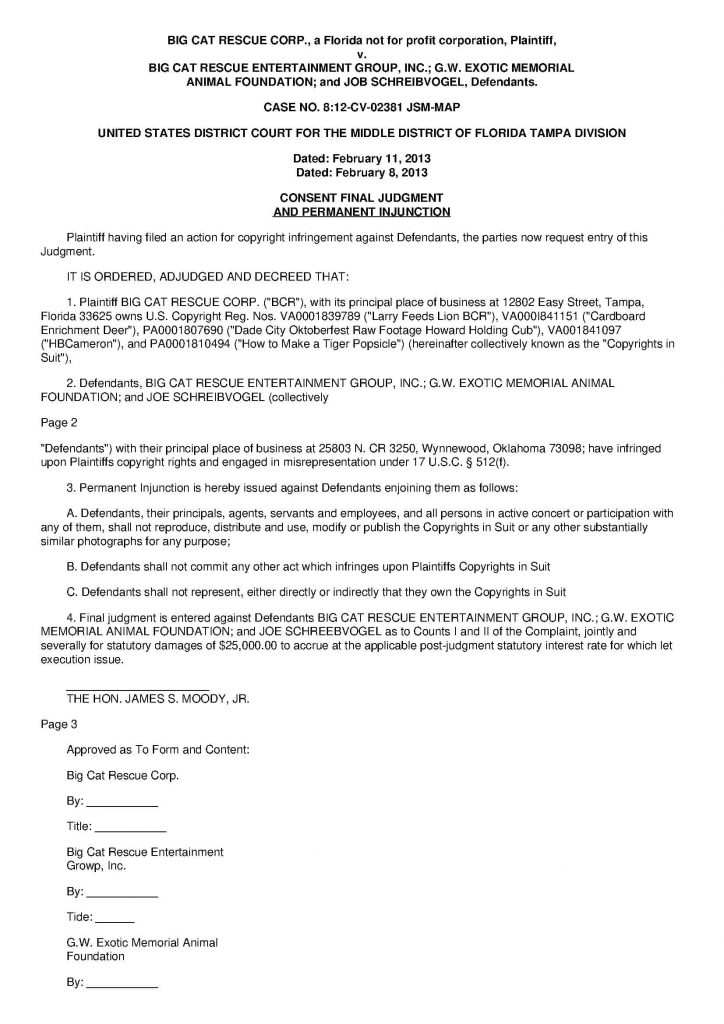

A King Dethroned

Carole and Joe’s legal feuding began in 2011 in a trademark infringement lawsuit that resulted in a judgment against Joe Exotic, ordering him to pay Baskin $1 million. This legal wrangling recently resurfaced in the news when Big Cat Rescue was given control of the 16 acres comprising the G.W. Zoo, formerly owned by Joe Exotic. The zoo and its animals were ordered to vacate the land within 120 days. Read some of the case law from Big Cat Rescue’s lawsuits against Joe Exotic and the various legal entities representing his zoo here.

Unwilling and unable to pay the $1 million judgment with his business decimated by Baskin’s persistent campaign against cub petting, Joe Exotic started selling off animals to raise cash for a murder-for-hire plot against Baskin. As we learned earlier, selling big cats across state lines is illegal under the CWSA amendment to the Lacey Act. Originally passed in 1900 to combat illegal commercial hunting by making it a federal crime to kill game in one state with the intent to sell it in another, the Lacey Act created rules and regulations governing the trade of wildlife, fish, and plants.

Already under federal investigation for murder-for-hire, once USDA agents started sniffing around the G.W. Zoo they uncovered the remains of five tigers buried on the property; subsequent investigations determined the healthy tigers had been shot to free cage space for other animals. Killing the animals without veterinary supervision was a violation of the Endangered Species Act, and the forms Joe Exotic falsified for the sale of tiger cubs across state lines compounded his charges. He was eventually convicted of eight counts of violating the Lacey Act for falsifying records in the transfer of wildlife and nine counts of violating the Endangered Species Act—one count for each of the tigers he killed and the rest in connection to the sale of tiger cubs across state lines. He was given two 12-month sentences on each Endangered Species Act violation and three 48-month sentences on each Lacey Act violation, in addition to the sentence for his murder-for-hire scheme against Baskin.

Don’t Be Socially Distant

If you feel passionate about the plight of tigers in captivity, think twice before getting your picture taken with a cub at the county fair, or contact your representative about their support for the Big Cat Public Safety Act. Why not share this post to help educate your fellow binge-watchers?

If you like learning the facts behind our current pop culture obsessions, subscribe to the HeinOnline blog for more great content like this delivered straight to your inbox.