Prior to the Civil War, African Americans weren’t allowed to receive an education. Black children weren’t allowed in schoolhouses. Many Black adults were unable to read, or even spell their own name. The Emancipation Proclamation may have freed the enslaved according to legislation, but truly, African Americans couldn’t achieve equality without education. And that’s where HBCUs, or Historically Black Colleges and Universities, came into play.

Educate Yourself in HeinOnline

Within HeinOnline’s various databases, you can find an extensive amount of information pertaining to the history and impact of HBCUs. From court cases to laws to journal articles, you can research the vast determination and courage that was the foundation of the struggle to achieve equal education and opportunities for Black students. To follow along with this blog post, check out some of these databases in particular:

- Civil Rights and Social Justice (available in our complimentary Social Justice Suite)

- Slavery in America and the World (available in our complimentary Social Justice Suite)

- Session Laws Library

- U.S. Supreme Court Library

What is an HBCU?

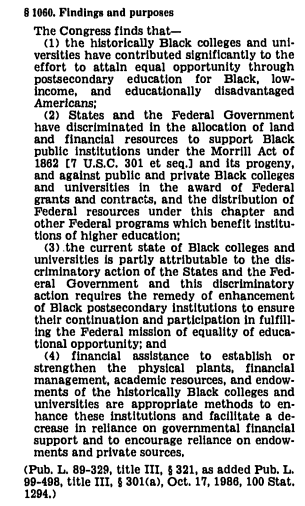

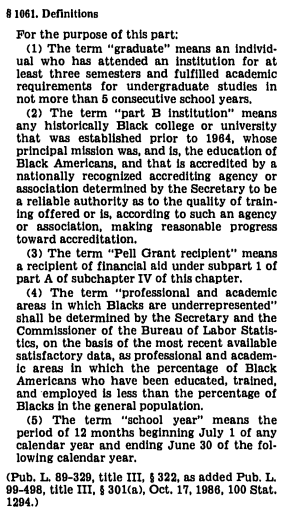

According to the amended Higher Education Act of 1965,[1]To strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary and higher education., Public Law 89-329, 89 Congress. 79 Stat. 1219 (1965). This act is located in … Continue reading an HBCU is defined as “…any historically black college or university that was established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation.”

The ultimate goal of HBCUs has changed over the years, but ultimately, they were created to provide quality education and opportunities to African American students—and they still fulfill this purpose today. Notable graduates of HBCUs include such respected names as Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Ida B. Wells, Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and current Vice President Kamala Harris, to name just a few.

Note: Historically Black institutions established after 1964 are referred to as Predominantly Black Institutions (PBI). According to the Higher Education Act of 2008, these schools must enroll at least 40% African American students, have a minimum of 1,000 undergraduates of which at least 50% are low-income or first-generation college students, and have low per full-time undergraduate student expenditure compared to similar schools.

Pre-Civil War

Up until the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans who wanted to learn had to rely on informal means of self-education. The first HBCU, called the Institute for Colored Youth,[2]W. E. Burghardt; Eaton Du Bois, Isabel. Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. was founded in 1832 in Cheyney, PA, by Quaker philanthropist Richard Humphreys, who wanted to help newly freed African Americans compete against the influx of European immigrants in the job market. This school later became Cheyney University. Other schools, such as Miner School for Girls (now University of the District of Columbia), Lincoln University, and Wilberforce University, opened their doors in the 1950s to Black students. However, these schools only provided elementary and secondary education, such as reading, writing, and math—HBCUs wouldn’t provide college courses until the early 20th century.

Emancipation & Segregation

Most HBCUs were founded after the Emancipation Proclamation.[3]Abraham Lincoln. Emancipation Proclamation (1950). This document is located in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. With the help of the American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau, there were seven Black colleges by 1870—including Howard, Fisk, Claflin, and Dillard universities.

Several laws and court cases over the next few decades would help to bring about even more HBCUs. For example, the Second Morrill Land Grant Act of 1890[4]To apply a portion of the proceeds of the public lands to the more complete endowment and support of the colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the mechanic arts established under the provisions of an act of Congress approved July second, … Continue reading designated that any state that created a land-grant institution solely for white students would need to create an equivalent institution for Black students. As a result, 16 land-grant colleges for African American students were established.

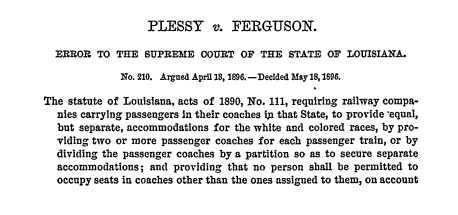

Plessy v. Ferguson[5]Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 563 (1896). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1896, the case that established the “separate but equal” clause justifying segregated schools, helped to validate the existence of institutions created solely for Black students. Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma[6]Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma et al, 332 U.S. 631, 632 (1948). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1948 would rule that states must provide equal schooling for Black students and white students. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents[7]McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education et al, 339 U.S. 637, 642 (1950). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1950 stated that Black students must receive the same treatment as white students. And Sweatt v. Painter[8]Sweatt v. Painter et al, 339 U.S. 629, 636 (1950). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. in 1950 deemed that the state must provide equal-quality educational facilities for Black and white students.

The Effects of Integration

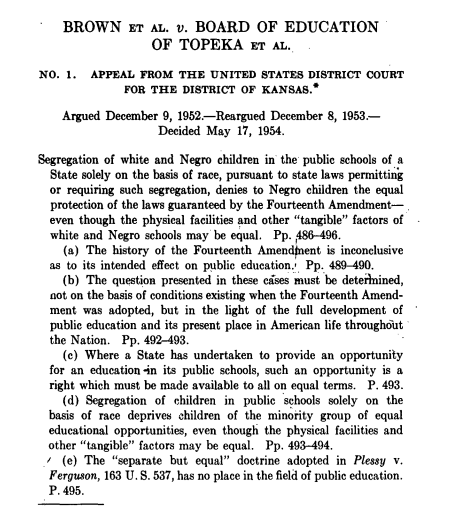

In 1954, the famous court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka[9]Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al, 347 U.S. 483, 496 (1954). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. ruled that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional—Black schools still were not receiving the same funding and resources as white students. However, HBCUs remained segregated, struggling with limited budgets, lower-quality facilities, and lack of library, scientific, and research resources. Eventually, many were forced to close or merge with primarily white schools.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VI[10]To enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations, to authorize the Attorney General to institute suits to … Continue reading was established to protect individuals from discrimination in programs that received federal funding—including schools. This led to the creation of the Office of Civil Rights (OCR), which focused, alongside the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), on eradicating unconstitutional segregation.

However, the effects were not immediate. The case Adams v. Richardson[11]351 F. Supp. 636. This case is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. found that OCR and HEW weren’t carrying out their duties, at the expense of Black students and their education. As a result, OCR established a plan for statewide desegregation—which also recognized the role of HBCUs in meeting the needs of Black students and established financial support for HBCUs, encouraging an increase of in-demand academic programs at HBCUs to increase enrollment of non-Black students. And in 1989, then President George Bush issued Executive Order 12677,[12]54 Fed. Reg. 18861 (1989), Tuesday, May 2, 1989, pages 18641 – 18872. This Executive Order is located in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. which was designed to further help HBCUs by increasing their participation in federal programs.

The HBCUs of Today

Today, HBCUs don’t enroll exclusively Black students. In fact, about 25% of HBCU students are Asian, Latino, immigrants, or white. However, the impact that these institutions have had on Black success cannot be understated. The majority of African American doctoral degrees came from HBCUs. These institutions—more than 20 of which subscribe to HeinOnline!—generally have high graduation rates, partially due to the fact they offer educational support programs and resources dedicated to minority students, and faculty are especially committed to students’ success. Black students can now apply to any university they so choose, but HBCUs remain relevant in cultural heritage, diversity, and maintain a lasting legacy in overcoming obstacles to help Black students receive the education and opportunities they deserve.

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | To strengthen the educational resources of our colleges and universities and to provide financial assistance for students in postsecondary and higher education., Public Law 89-329, 89 Congress. 79 Stat. 1219 (1965). This act is located in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | W. E. Burghardt; Eaton Du Bois, Isabel. Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899). This book is located in HeinOnline’s Civil Rights and Social Justice database. |

| ↑3 | Abraham Lincoln. Emancipation Proclamation (1950). This document is located in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑4 | To apply a portion of the proceeds of the public lands to the more complete endowment and support of the colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the mechanic arts established under the provisions of an act of Congress approved July second, eighteen hundred and sixty-two., Chapter 841, 51 Congress, Public Law 51-841. 26 Stat. 417 (1890). This act is located in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑5 | Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 563 (1896). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑6 | Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma et al, 332 U.S. 631, 632 (1948). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑7 | McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education et al, 339 U.S. 637, 642 (1950). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑8 | Sweatt v. Painter et al, 339 U.S. 629, 636 (1950). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑9 | Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al, 347 U.S. 483, 496 (1954). This case is located in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑10 | To enforce the constitutional right to vote, to confer jurisdiction upon the district courts of the United States to provide injunctive relief against discrimination in public accommodations, to authorize the Attorney General to institute suits to protect constitutional rights in public facilities and public education, to extend the Commission on Civil Rights, to prevent discrimination in federally assisted programs, to establish a Commission on Equal Employment Opportunity, and for other purposes., Public Law 88-352, 88 Congress. 78 Stat. 241 (1964). This act is located in HeinOnline’s Session Laws Library. |

| ↑11 | 351 F. Supp. 636. This case is located in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑12 | 54 Fed. Reg. 18861 (1989), Tuesday, May 2, 1989, pages 18641 – 18872. This Executive Order is located in HeinOnline’s Federal Register Library. |