Dred Scott v. Sandford, a Supreme Court decision made in 1857, is largely regarded as one of the most infamous decisions in the Supreme Court’s history. This case determined that people of Black African descent were not entitled to citizenship via the U.S. Constitution, and therefore, they did not have any of the rights granted to white Americans, including the right to sue in court. In this post, we’ll use various databases in HeinOnline, including Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law, U.S. Statutes at Large, and the U.S. Supreme Court Library, to explore the political climate that led to such a heinous decision, as well as the case and its aftermath. Additionally, keep reading to learn more about Dred Scott v. Sandford: Opinions and Contemporary Commentary, a title by Douglas W. Lind and available from Hein.

Don’t have time to read the post? Go ahead and click the headphones icon toward the bottom-right of the screen to hear an audio version!

Slave vs. Free

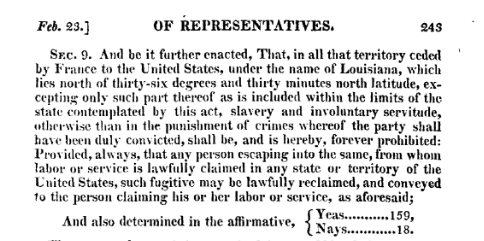

In 1810, the United States purchased 530,000,000 acres of territory from France for $15 million. This wide swath of land was nicknamed the Louisiana Purchase[1]France and Spain – Louisiana Purchase (7-2), 2 American State Papers: Foreign Relations 506 (1802). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set.—but Northerners and Southerners argued over whether slavery would be legalized or not within the newly acquired states. The 1820 Missouri Compromise[2]To authorize the people of the Missouri territory to form a Constitution and state government, and for the admission of such State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States, and to prohibit slavery in certain territories., Chapter … Continue reading determined that Maine would enter the nation as a free state, while Missouri would be a slave state. Beyond those two states, any area north of the parallel 36°30′ north would be free,[3]“House Journal, 16th Congress, 1st Session.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1819, pp. 1-652. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset49625&i=243. This document can be found in … Continue reading and any area south would legalize slavery. However, what would happen if a slaveowner took an enslaved person from a slave territory to a free territory? Would they legally be free? This wasn’t determined until the Dred Scott decision.

Who Was Dred Scott?

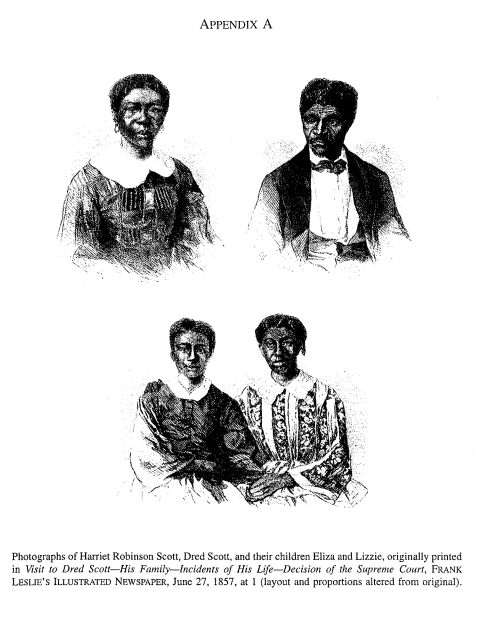

Dred Scott was an enslaved man who was born in Virginia in 1799. He was purchased by Army surgeon Dr. John Emerson in 1830. Due to his occupation, Emerson was frequently reassigned to different locations. First, he moved to Fort Armstrong[4]Army Register, 1834 (23-1), 20 American State Papers: Military Affairs 277 (1833). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. in Illinois, and he took Scott with him. A few years later, in 1836, Emerson and Scott moved to Fort Snelling[5]Army Register, 1837 (24-2), 21 American State Papers: Military Affairs 1004 (1836). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. in the Wisconsin Territory, which was where Minnesota is today. While in Fort Snelling, Dred Scott married Harriet Robinson, and because they were in a free territory,[6]Lea Vandervelde, The Dred Scott Case in Context, 40 J. Sup. CT. Hist. 263 (2015). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. they were able to legally marry via a civil ceremony.

Emerson left Fort Snelling in 1837, but he had Scott and his wife remain while he leased out their services. He was reassigned to Fort Jessup in Louisiana later that year, and in 1838 he sent for Scott and Harriet to serve him and his new wife, Irene. At this point, Scott could have sued the Emersons for his freedom, as he had been in a free territory, but it’s unclear if he was sure of his legal rights at this time. Meanwhile, Emerson was reassigned back to Fort Snelling toward the end of 1838, and Irene Emerson returned to St. Louis with Scott and his wife, where she once again leased out their services. Once Emerson died in 1843, Irene inherited his estate, which included his enslaved peoples.

In 1846, Scott tried to purchase his family’s freedom—at this point, he and Harriet had two daughters—but Irene Emerson refused to free them. Scott then sued in the Circuit Court of St. Louis County.

A Series of Courts

Surprisingly, Scott received help suing the Emersons from the Blow family, which had owned him before he was sold to Dr. Emerson. It was expected that his case would win in the Circuit Court of St. Louis, as Winny v. Whitesides[7]1 Mo. 472 WINNY v. WHITESIDES ALIAS PREWITT. Supreme Court of Missouri. This case can be found in Fastcase. and Rachael v. Walker[8]4 Mo. 350 RACHAEL, A WOMAN OF COLOR, v. WALKER. Supreme Court of Missouri. This case can be found in Fastcase. had set the precedent that enslaved people were free once they were brought to free territory. Additionally, Missouri had laws in place at the time that allowed people of color to sue for wrongful enslavement, and that stated that anyone brought to a free territory was free and could not be enslaved again once they returned to a slave state. However, Scott lost the case on a technicality, and his appeal to the Missouri supreme court was denied.

In his second state circuit court trial, Scott actually won the case, but Irene Emerson’s legal team appealed, and she won on the appeal.

In time, Irene Emerson transferred her late husband’s estate to her brother, John F.A. Sanford. In 1853, Scott sued John Sanford in federal court for his family’s freedom. Scott lost the case and appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Sanford’s name was misspelled as Sandford[9]Paul Finkelman, Editor. Southern Slaves in Free State Courts: The Pamphlet Literature (2007). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. in the court records, hence why the case is listed as Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Corruption in the Supreme Court

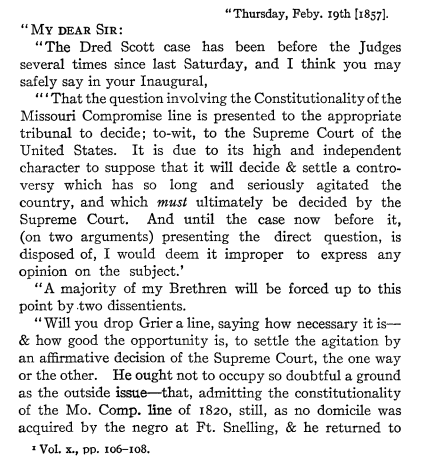

At the time of the Supreme Court case, James Buchanan had been elected president, and he wanted the Dred Scott decision to provide a means of unifying the nation over the slavery question. So, he contacted Supreme Court Associate Justice John Catron to learn information about the status of the case.[10]Daniel Wait Howe. Political History of Secession to the Beginning of the American Civil War (1914). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. He proceeded to pressure Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier—a Northerner who otherwise may have sided with Scott—to join the majority opinion[11]Daniel Wait Howe. Political History of Secession to the Beginning of the American Civil War (1914). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. in the case to avoid making it look like the Court was divided on sectional lines, North vs. South. In his inaugural address,[12]Jonathan French. True Republican: Containing the Inaugural Addresses, Together with the First Annual Addresses and Messages, of all the Presidents of the United States, from 1789 to 1857 (1857). This speech can be found in … Continue reading Buchanan publicly supported the unreleased Court decision, stating that the question of whether enslaved people brought to a free territory were forever freed was “happily a matter of but little practical importance”[13]Jonathan French. True Republican: Containing the Inaugural Addresses, Together with the First Annual Addresses and Messages, of all the Presidents of the United States, from 1789 to 1857 (1857). This speech can be found in … Continue reading that would be settled by the Supreme Court “speedily and finally.”

Two days later, on March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court ruled against Scott in a 7-2 decision.[14]Dred Scott, Plaintiff in Error, v. John F. A. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 634 (1856). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. In the majority opinion, penned by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court stated that African-Americans “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.” Hence, this meant that no enslaved person had rights under the Constitution, including the right to sue in court. It also effectively nullified the Missouri Compromise, although it had already been repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act,[15]To organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas., Chapter 59, 33 Congress, Public Law 33-59. 10 Stat. 277 (1854). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. which created two new territories where popular sovereignty would determine if slavery would be legalized or not.

Now, … the right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution. … Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the act of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning property of this kind in the territory of the United States north of the [36°N 30′ latitude] line therein mentioned is not warranted by the Constitution, and is therefore void….

The Aftermath

Abolitionists were furious over the Dred Scott decision—including Abraham Lincoln. In fact, the decision would be a topic discussed in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, a series of seven debates hosted in 1858 between Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate, and Stephen Douglas, the Democratic candidate—which we covered in depth in a previous edition of Secrets of the Serial Set.

Dred Scott and his family were eventually emancipated. Irene Emerson remarried, and her husband, Calvin C. Chaffee, was ironically an abolitionist, and being the Scotts’ owner gave him a lot of negative publicity.[16]David T. Hardy, Dred Scott, John San(d)ford, and the Case for Collusion, 41 N. KY. L. REV. 37 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. He transferred the Scott family to Henry Taylor Blow, the son of Scott’s former owner and the man who helped Scott take the Emersons to court. Blow freed the Scotts, and they were officially emancipated on May 26, 1857. But unfortunately, Scott did not get to live long as a free man—he died less than a year later from tuberculosis.

Today, the Dred Scott decision is generally regarded as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions due to its outright racism. It also served as yet another factor that contributed to the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War and inflamed sectional differences between North and South, abolitionists and slaveowners.

Dive Deeper with Dred Scott v. Sandford: Opinions and Contemporary Commentary

The decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), that African Americans were unable to become American citizens and therefore lacked standing to sue in federal court, and that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories, was truly monumental in its impact on the nation and immediately generated widespread public debate. For more than one hundred and fifty years, there existed no single source containing the nine opinions that comprise the Dred Scott decision alongside the contemporary intellectual commentary. Dred Scott v. Sandford: Opinions and Contemporary Commentary not only fills that scholarly void but also includes Professor Lind’s bibliographic essay which traces the production and transmission history of Dred Scott and details many previously unrecorded bibliographic aspects of the separately printed decision. In doing so, Lind adds important elements to the historiography of a landmark in American judicial thought—a decision which provided the textual ammunition for both sides of a debate that further divided the nation as it marched toward civil war.

Dred Scott v. Sandford:

Opinions and Contemporary Commentary

Author: Douglas W. Lind

Item #: 1006043

ISBN: 978-0-8377-4061-4

Pages: xix, 663p.

Paper………$85.00

Published: Getzville; William S. Hein & Co., Inc.; 2017

HeinOnline Sources[+]

| ↑1 | France and Spain – Louisiana Purchase (7-2), 2 American State Papers: Foreign Relations 506 (1802). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | To authorize the people of the Missouri territory to form a Constitution and state government, and for the admission of such State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States, and to prohibit slavery in certain territories., Chapter 22, 16 Congress, Public Law 16-22. 3 Stat. 545 (1820). this statute can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑3 | “House Journal, 16th Congress, 1st Session.” U.S. Congressional Serial Set, , 1819, pp. 1-652. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.usccsset/usconset49625&i=243. This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Serial Set. |

| ↑4 | Army Register, 1834 (23-1), 20 American State Papers: Military Affairs 277 (1833). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑5 | Army Register, 1837 (24-2), 21 American State Papers: Military Affairs 1004 (1836). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Congressional Documents database. |

| ↑6 | Lea Vandervelde, The Dred Scott Case in Context, 40 J. Sup. CT. Hist. 263 (2015). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |

| ↑7 | 1 Mo. 472 WINNY v. WHITESIDES ALIAS PREWITT. Supreme Court of Missouri. This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑8 | 4 Mo. 350 RACHAEL, A WOMAN OF COLOR, v. WALKER. Supreme Court of Missouri. This case can be found in Fastcase. |

| ↑9 | Paul Finkelman, Editor. Southern Slaves in Free State Courts: The Pamphlet Literature (2007). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑10, ↑11 | Daniel Wait Howe. Political History of Secession to the Beginning of the American Civil War (1914). This document can be found in HeinOnline’s Slavery in America and the World: History, Culture & Law database. |

| ↑12, ↑13 | Jonathan French. True Republican: Containing the Inaugural Addresses, Together with the First Annual Addresses and Messages, of all the Presidents of the United States, from 1789 to 1857 (1857). This speech can be found in HeinOnline’s World Constitutions Illustrated database. |

| ↑14 | Dred Scott, Plaintiff in Error, v. John F. A. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 634 (1856). This case can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Supreme Court Library. |

| ↑15 | To organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas., Chapter 59, 33 Congress, Public Law 33-59. 10 Stat. 277 (1854). This act can be found in HeinOnline’s U.S. Statutes at Large database. |

| ↑16 | David T. Hardy, Dred Scott, John San(d)ford, and the Case for Collusion, 41 N. KY. L. REV. 37 (2014). This article can be found in HeinOnline’s Law Journal Library. |